Scientist of the Day - Empedocles

Empedocles, a Greek pre-Socratic natural philosopher, lived and wrote sometime around 440 B.C.E; he was probably born around 490 and died about 434 B.C.E. He was born in Akragas (Agrigentum to the Romans) on the southwest coast of Sicily, part of what was then called Magna Graeca, Greater Greece. Nothing is really known of his life, but he did write two books, one of which, On nature (written in verse), addressed the same problems of the nature of matter and substance as had predecessors such as Thales, Anaximander, Heraclitus, and Parmenides. Parmenides was an especially strong influence on Empedocles, it would seem. Quite a few fragments of Empedocles’ books survive, more than any other pre-Socratic philosopher, taking up 18 pages in Kathleen Freeman's Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers (1971, pp. 51-69).

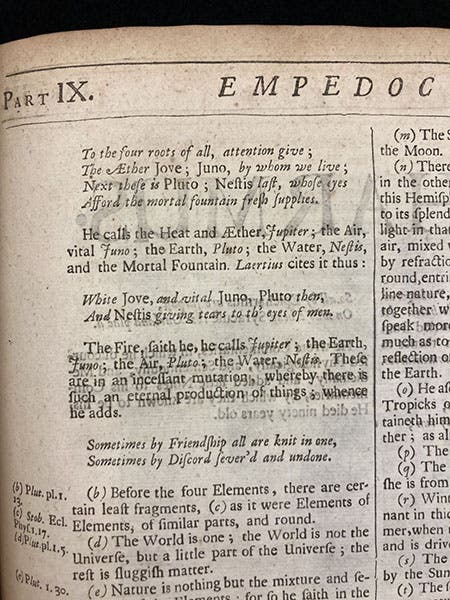

Empedocles is credited with being the first to propose that all substances are combinations of the four elements: earth, water, air and fire. Actually, he called these rhizomata, “roots,” and he believed that the roots are eternal entities. This is a new thought, that most substances are made up from simpler parts that are uncreated. Since all substances are made of the same four roots, there must be different proportions of elements in different substances, such as bone, and blood, to mention two substances that Empedocles used as examples. Proportion was a hot topic among the Pythagoreans in Croton, in southern Italy, not far from Sicily, and possibly Empedocles was influenced by them. Empedocles proposed that the elements or roots are brought together by a natural force, which he calls philotês, or philia, or sometimes harmonia, and is usually translated as Love (remember, Empedocles was a poet); substances are broken up by a force of dissolution, which he calls dismáchi or Strife. Four elements, two cosmic forces of attraction and repulsion – you could build a physics of matter from those ingredients. Aristotle would soon do so.

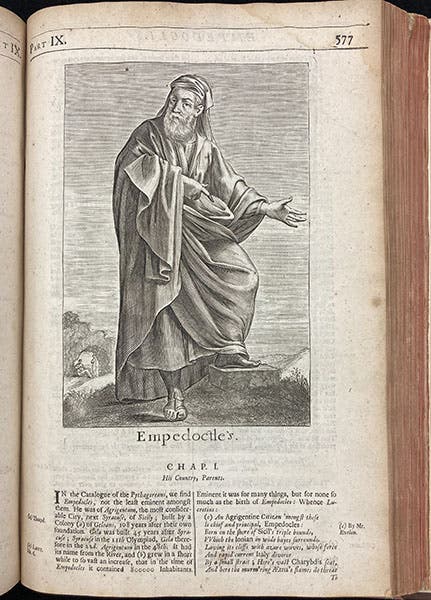

We have a fascinating 17th-century book in our collections called The History of Philosophy: Containing the Lives, Opinions, Actions and Discourses of the Philosophers of Every Sect, by Thomas Stanley. It was originally published in parts; we have the second edition of 1687, published in one volume. Stanley did an acceptable job of extracting information on the pre-Socratics from Aristotle and Diogenes Laertius and others (a better understanding of pre-Socratic philosophy would come only in the late 19th and 20th centuries). Unlike later scholars, Stanley preserved the verse form when he translated the fragments. Here is one of them, about Love and Strife:

Sometimes by Friendship all are knit in one

Sometimes by Discord severed and undone

I think I like natural philosophy in rhyming couplets.

Stanley also provided portraits for many of his ancient philosophers. The engravings vary in quality – that of Plato is excellent and seems to have been based on Renaissance portrayals of Plato – while that of Aristotle seems off the wall. But for many of the pre-Socratics, we have no other portraits, so the Empedocles we show here as our first image is Stanley's engraving, and we are happy to have it, because the alternative would be the tiny woodcut in the Nuremberg Chronicles, which is generic to the extreme. There is a statue in modern Agrigento, but it is so dreadful (it looks like Caesar conquering Gaul) that I won't show it here, although you can take a look at this link.

I will conclude with my favorite Empedoclean fragment, no. 28. I have no idea what it means, but I love the last two words:

28. But he (God) is equal in all directions to himself and altogether eternal, a rounded sphere enjoying a circular solitude.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.