Scientist of the Day - Ernst Chladni

Ernst Friedrich Chladni, a German physicist, died Apr. 3, 1827, at the age of 70. Born in Wittenberg, Chladni was trained to be a lawyer, at his father's insistence, but when his father died in 1782, Chladni was free to pursue his own interests, which centered around physics and music. When he was just 31 years old, he published a book called Entdeckungen über die Theorie des Klanges (Discoveries in the Theory of Sound, 1787); we have this work in our History of Science collection. The title page is shown below.

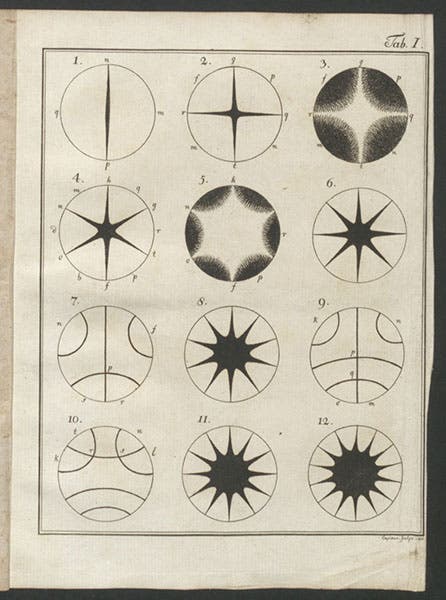

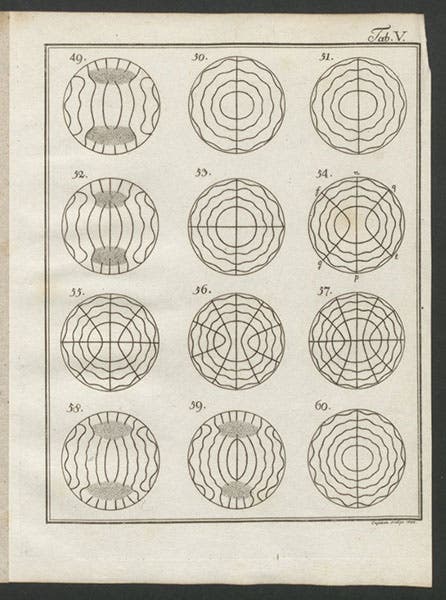

In this work, Chladni made a detailed experimental study of the behavior of vibrating plates. Until Chladni, no one had any idea how surfaces move in response to vibration, because no one had figured out how to make the plate motion visible. Chladni did just that. He made thin brass plates about sixteen inches square, mounted them horizontally, covered them with fine sand, and then set them in motion by stroking the plates with a rosined bow. As the plate vibrated, the sand moved into what Chladni called nodal lines, the areas where the plate was not moving. The result was a pattern of lines, which changed when you change the point on the plate where you strike with the bow, or when you touch the edge of the plate with a finger or fingers of your other hand. Wherever you stroke with the bow, the plate moves; where you touch it with your fingers, the plate stays still, and nodal lines will radiate out from your fingers.

In his book, Chladni published a series of engraved plates with hundreds of patterns that he had observed. We show two of the plates here, as well as the title page. The part of a plate covered with sand is black. The patterns have come to be called Chladni patterns or Chladni figures. It is easy to produce them in the lab, or even in your home, since they require no equipment other than a metal plate, a bow, and some sand or other fine material. There are many videos of Chladni patterns available online. Most of them use tonal generators to vibrate the plate, which to me, takes much of the fun out of it. So I link you to a video where the demonstrator uses a bow, just like Chladni, and who prefers to use couscous instead of sand. Why not? Here is the 3 ½ minute video.

Chladni's other major scientific contribution came in an entirely different field, the study of meteorites. In 1794, when he published a book on the subject, most geologists thought that meteorites had some kind of terrestrial origin. Stories of stones that fall from the heavens were generally disbelieved. Stories of fireballs were more acceptable, but those phenomena were thought to have something to do with volcanic activity or combustible gases released from the Earth. Astronomers believed, still following Aristotle, that the heavens had planets and nothing else – there were no loose stones flying through space. Asteroids had yet to be discovered, so there was no way to explain how stones could fall from the sky.

In his Über den Ursprung der von Pallas gefundenen und anderer ihr ähnlicher Eisenmassen und über einige damit in Verbindung stehende Naturerscheinungen, (On the Origin of the Pallas Iron and Other Similar Iron Masses, and on Some Associated Natural Phenomena, 1794), Chadni argued that meteorites have their origin in cosmic space, sometimes arriving on earth individually, and sometimes the result of a fireball, where a rock from space explodes in the atmosphere and showers the Earth with debris. The Pallas iron in his title was a large and peculiar stone, some 1500 pounds in weight, encountered by Peter Simon Pallas on travels to Siberia and eventually hauled to St. Petersburg. We see below a lithograph of a piece of the Pallas iron from a work of 1820 in our collections.

It is not clear whether Chladni ever saw the Pallas iron, or an actual fall of stones, although we know he did collect meteorites. His book was published in Germany and had little influence on observers of meteorite falls in France, Italy, and England. But it happened to coincide with a dramatic fall of stones in Siena, Italy (which occurred some months after Chladni’s book was published), and in the next ten years, there was a rapid turn-around in scientific attitudes toward meteorites. By 1804, nearly everyone agreed that meteorites have an extraterrestrial origin. So even though Chladni’s book didn’t really influence anyone, it coincided with the beginning of a revolution in the understanding of meteorites, and so Chladni is often called the “father of meteoritics.” We have discussed other key figures in this turnabout; if you are interested, you might check out the posts on: Peter Simon Pallas, Jean-Baptiste Biot, Edward Charles Howard, Ambrogio Soldani, Aloys von Widmanstätten, and Karl von Schreibers (the source of our sixeth image)

Chladni also designed and built musical instruments. A hot ticket on the chamber music circuit in the 1780s and 90s was the glass harmonica, invented by Benjamin Freanklin (here is a photo of a replica of a Franklin instrument). It consisted of a series of glass bowls of different sizes mounted on a rotating horizontal shaft in a water bath; when the rotating bowls were stroked by a player’s fingers, the bowls made a beautiful if ethereal sound. But the glass harmonica, popular though it was, had some drawbacks, including one that Chladni was the first to point out in his book: when you touch a moving glass bowl with your finger, the way it vibrates depends very much on where you place your fingers, just as with his brass plates. So he set out to make an instrument that produced the same tones all the time. His first success was the euphone, which had glass rods instead of bowls that were stroked by the player. It had the advantage of being more portable than the heavy and delicate glass harmonica. His second instrument was the clavicylinder (seventh image, above). This had a series of curved metal or wooden strips attached to a keyboard; when a key was depressed, the corresponding strip was pressed against a rotating cylinder, producing a tone. Since this was a keyboard instrument, one could play any Telemann or Mozart piece on it with no transcription. Surviving clavicylinders are scarce, and I could find only one image and no videos freely available online. So I link to a video of a similar but later instrument, the terpodion, not made by Chladni, dating to 1825, but it does show how the rotating cylinder works. Click the arrow here to start the 30-second video.

Chladni never held an academic position, so he earned his living by touring, demonstrating his vibrating plates, playing his instruments, or lecturing on meteorites. He did this for almost 30 years, and it was a difficult life. But Napoleon apparently took a shine to Chladni, and paid him to translate his second book on acoustics into French. It was published in 1809 as Traité d'acoustique. We have this work in our collection as well.

Chladni died and was buried in the Great Cemetery in Breslau, Lower Silesia, now Wrocław, Poland. I do not know if he has any kind of monument, as I was unable to find a photograph of his grave.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.