Scientist of the Day - Eugene Schieffelin

Eugene Schieffelin, a New York City pharmacist and drug manufacturer, was born Jan. 29, 1827. We have celebrated the birthdays of quite a variety of people in this space, most of them brilliant or clever or industrious or otherwise admirable, and a few who had measurable shortcomings, but I dare say we have never featured anyone who arouses as much derision and distaste from Americans as Mr. Schieffelin. For he was the man who introduced the starling into the United States in 1890.

Schieffelin was chairman at the time of the American Acclimatization Society, a group that had been founded in 1871. Acclimatization Societies first appeared in France in the 1850s, and then spread to Britain and, eventually, to the United States. The aim of these organizations was to introduce exotic animals and plants into a country to provide more floral and faunal variety, and perhaps some economic gain. The American version was centered in New York City, and Schieffelin was already its chairman by 1877. It is nearly always stated as a fact that Schieffelin's goal was to introduce into Central Park every bird mentioned in the plays of Shakespeare. This may be true. Shakespeare does indeed mention a starling in Henry IV Part I. But if there is any contemporary evidence that this was Schieffelin's motivation, it is never cited, and so I am more than a little skeptical. But it does make a nice story. And it is true that some of the birds he tried introducing before the starling venture – birds such as the nightingale and the chaffinch – were indeed Shakespearean birds. None of these attempted transplants, by the way, was successful.

The starling's turn came in 1890. Schieffelin had 60 birds collected in England and brought to New York, where he released them in Central Park. The next year, he followed up with 40 more – in all, a century of starlings. Unlike the nightingales, the starlings responded to their transplantation, as they do to most things, with enthusiasm. They settled right into the park and prospered. It took them quite a while to get out of the city – some things haven’t changed – but by 1930, they had crossed the Mississippi, and by 1950, they had spread to the West Coast. They soon numbered in the tens of millions. Sometimes nearly half that number seem to be in your back yard. One should not be too hard on Eugene. Hundreds of people in dozens of countries were bringing in emus and flowering cherries and gypsy moths, and no one was waving a flag of caution. Ecological thinking was as yet a gleam in only a few peoples' eyes. Still, many wish that Schieffelin had not done what he did.

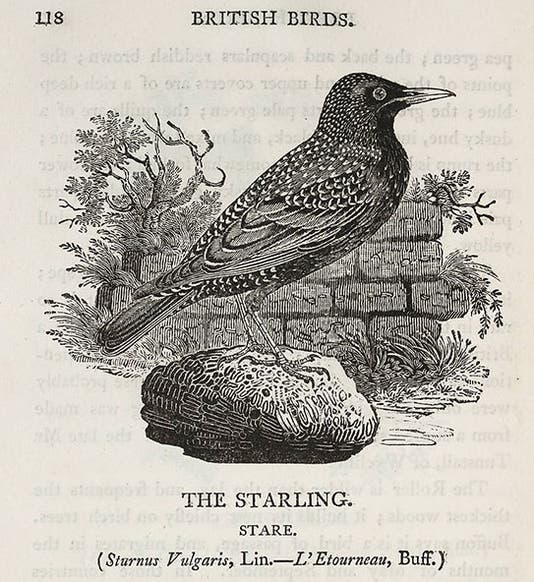

I, however, am rather fond of starlings. They are the brassiest of birds, and they fly like an old F-4 Phantom, and they don’t take any flak from blue jays. What’s not to like? Many years ago, I bought a hand-colored print by John Gould, the great English bird illustrator. Gould prints can be very expensive, and I didn't have much money, so I bought the cheapest Gould print I could find in London. It depicted a family of starlings, and we framed it and hung it in our living room (where it still hangs), and when my kids were little, they had names for the babies – Wendell and Orville are the only two I can remember. If I had educated them properly, they would have called one of them Mortimer. My starling print has not been photographed, so we show you one in the Brooklyn Museum. Gould made this print for his Birds of Great Britain (1873), and it is sobering to think that, when he did so, there were no starlings in the United States. Who knows, perhaps Wendell or Orville or one of their descendants made it to New York in that momentous trans-Atlantic crossing of 1890-91. If so, they have an estimated 200 million great-great-…-great-great grandfledglings, thanks to Eugene Schieffelin. We have no portraits of Schieffelin, and although he was buried in the prestigious Green-wood Cemetery in Brooklyn – along with Samuel F.B. More and Currier & Ives – there seems to be no pictorial record of his tombstone. So for images today, we show you starlings – English starlings. I have been trying to determine the first American bird book to include a picture of a starling, but so far, without success. When I do, I will update this paragraph. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.