Scientist of the Day - Everard Home

Everard Home, a British anatomist and surgeon, was born May 6, 1756. Home was the brother-in-law of John Hunter, who amassed a considerable anatomical museum for his personal pleasure. After Hunter's death, Home convinced the government to buy the museum for the Royal College of Surgeons, and he became the Museum's principal curator.

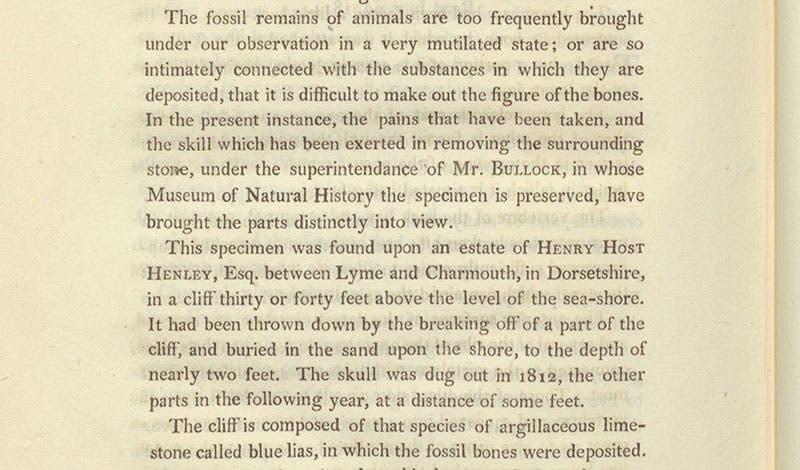

In 1814, Home wrote a paper for the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London about a new fish-like creature that had been discovered in Lyme Regis on the Dorset coast. The paper was called "Some account of the fossil remains of an Animal more nearly allied to Fishes than any of the other Classes of Animals," and on the second page (third image, below), Home explained how the fossil came to his attention. He mentioned that it was found in 1812 and 1813 on the property of Henry Host Henley in Dorset, and that it was now in the Museum of Mr. Bullock. Home failed to mention that the specimen was found by a 12-year-old girl, Mary Anning, with the help of her older brother Joseph.

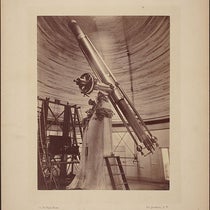

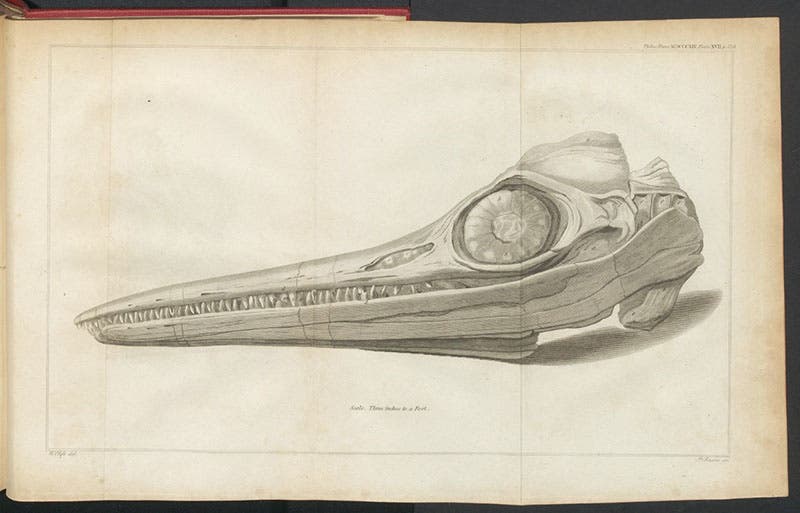

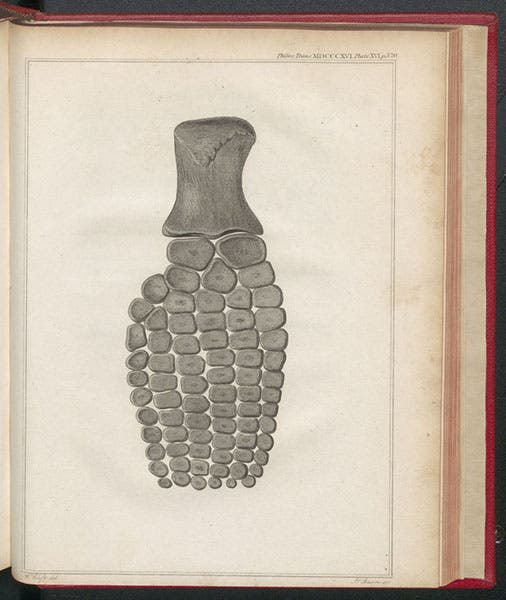

Home wrote four more papers about Mary Anning’s specimen, without once mentioning her name. He did include some fine engravings, the first published illustrations of any of Mary Anning’s finds – the skull in the first paper of 1814 (fourth image), a paddle in a paper of 1816 (fifth image), and in the final two papers of 1819, there was attached a splendid quadruple folding plate, showing a nearly complete skeleton that had been found by Mary in 1818 (first image, with a detail as seventh image). All of the drawings were beautifully rendered by the conservator at Hunter’s Museum, William Clift, and engraved by the Royal Society’s engraver, James Basire II.

In the final two papers of 1819, Home attempted to name the specimen Proteosaurus, but that name never stuck, the term Ichthyosaurus being preferred by Henry de la Beche and William Conybeare. De la Beche and Conybeare (and William Buckland) properly recognized Mary Anning as the discoverer.

Home published many papers on anatomy in the 1810s and 1820s, and, very curiously, in 1823, he destroyed all the papers of John Hunter that were in his possession. After Home’s death in 1832, at an inquiry in 1834, Clift testified that much of his time at the museum had been devoted to copying the unpublished manuscripts of John Hunter, of which there were many. It is strongly suspected that most of the papers published by Home under his own name were actually written by Hunter.

The five papers on Mary Anning’s ichthyosaurus were not plagiarized from John Hunter. But it is now not so surprising that Home did not give credit to Anning where it was due.

The other authentic survivor of Home’s fraudulent career was William Clift. He was a much better anatomist than Home, and a gifted artist, who drew for publication not only the three plates shown here, but also the Pterodactyl later discovered by Anning, and the Megatherium found in South America by Woodbine Parish. We displayed these and others in an earlier post on Clift. Below we honor his artwork with a detail of our first image, his engraved drawing of Mary Anning’s Ichthyosaurus skeleton, found in 1818.

There is a portrait of an older (and rounder) Everard Home in the Royal Society of London; you can see it here. We prefer to include, as our portrait, one depicting the younger scoundrel, made when he was just starting out on his nefarious career (second image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Detail of first image, showing the skull of [Proteosaurus], as drawn by William Clift and engraved by James Basire II (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1735408e-face-40b5-8d9b-21b3c43a0aaa/home7.jpg?w=800&h=492&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)