Scientist of the Day - Federico Commandino

Federico Commandino, an Italian mathematician, died Sep. 5, 1575, at age 66. Commandino grew up in Urbino, learned mathematics from a tutor for the Duke, and found his life calling. For some reason he studied for a degree in medicine at Ferrara, and he practiced medicine for a while, being the physician for various patrons, but the death of his father, wife, and son in short succession seems to have soured him on medicine, which seemed of little use in saving people’s lives, and so he returned to math.

Commandino became the principal figure behind the revival of Greek mathematics, especially the work of Archimedes, in the last half of the 16th century. The works of the great Greek mathematicians, such as Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy, Apollonius, and Pappus of Alexandria, existed mainly in manuscript, and most of these manuscripts were incomplete, and many had been translated from Greek to Arabic to Latin, with multiple errors creeping in at each stage of translation. Commandino had access, through his many patrons, such as the Cardinal Farnese, to multiple manuscript versions of most of the important works, so he was able to collate the different versions and tease out the correct text. Fortunately, he was an excellent mathematician and could complete proofs that were incomplete, and correct those that were wrong.

Commandino’s goal was to make all of the surviving works of the Greek mathematicians available in print in Latin translations, adding his own commentaries whenever possible. He began with five of the works of Archimedes in 1558, published in Venice by the famous Manutius press, and he continued right through his death (from overwork) in 1573, as two of his translations were published in 1575, and one final one in 1588.

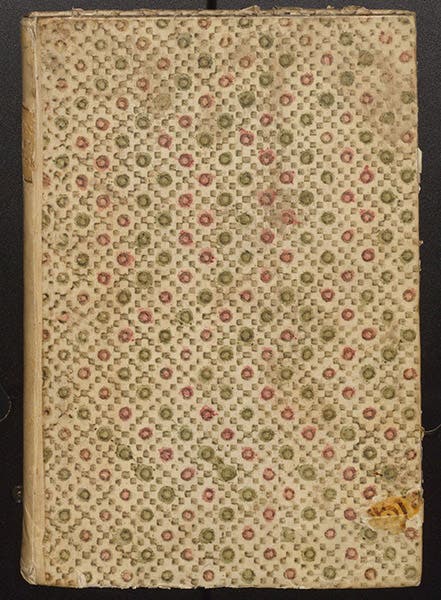

We do not have all the works of Commandino in our collections, but we have a good chunk of them, some 14 titles, a few in multiple copies or multiple editions. We have not only the 1558 Archimedes (fourth and fifth images), but a separate printing of Archimedes’ On Floating Bodies (Bologna, 1565), which would have such an influence of Galileo Galilei. We have, as well, Commandino’s editions of the Conics of Apollonius (Bologna, 1566), Euclid’s Elements (Pesauro, 1572), and a translation of Euclid into the Italian vernacular, published after his death, in 1575 (eighth image). Our copy of the Conics of Apollonius was once in the library of Harrison Horblit and has his bookplate, as well as a lovely paper binding (sixth image).

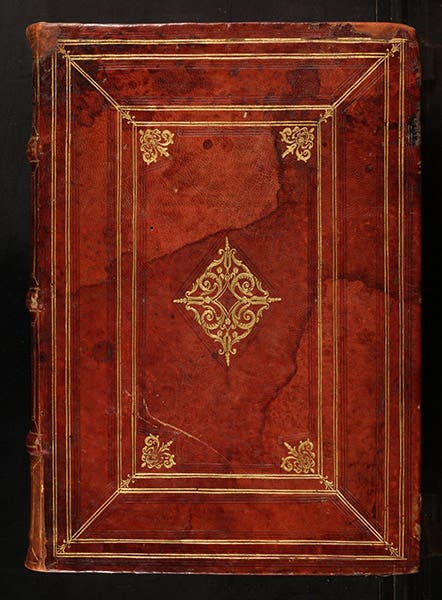

One of the most attractive Commandino publications in our collections is a translation of the Analemmata of Ptolemy of Alexandria, published by the Aldine press in Rome in 1562 (first image). Although written by an astronomer, it deals with a mathematical problem – how to predict the position of the Sun in the sky for a particular day, time, and latitude – and thus requires lots of intricate diagrams. Our copy sports a later morocco binding with the device of Aldus Manutius stamped on the red front cover (third image).

Another attractive book is the posthumous edition of the Pneumatics of Hero of Alexandria (1575), which is not mathematical at all, but seems to have attracted the attention of Commandino anyway. Since it concerns mechanics, rather than math, its diagrams are more appealing to the ordinary viewer, with its depictions of automata activated by hydraulic and pneumatic mechanisms (seventh image).

Not only did Commandino kick-start the recovery of ancient Greek mathematics, but he attracted younger colleagues, such as Guidobaldi del Monte, to follow in his footsteps, thereby establishing what we call the Urbino school of mathematics. The Archimedean revival they launched had a great influence on young Galileo Galilei.

There is a single surviving oil portrait of Commandino, and even though it is often reproduced, no one is saying where we can find the original (second image). It is stylistically similar to several portraits (such as one of Nicolas Steno) in the Uffizi in Florence, which might make it a 17th-century posthumous portrait, but that is OK – certainly better than no portrait at all. If anyone knows where one can find Commandino’s oil portrait, please let me know. I have been curious for a long time.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.