Scientist of the Day - Filippo Buonanni

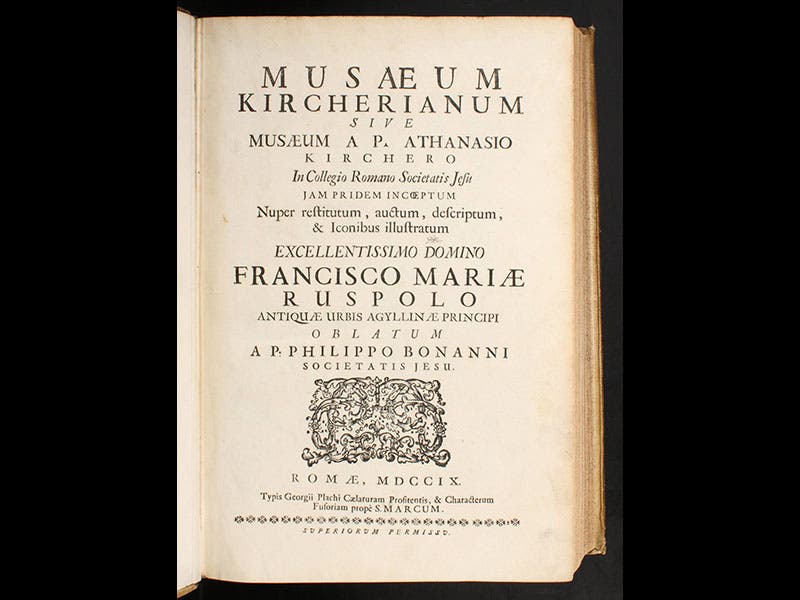

Filippo Buonanni, an Italian Jesuit, was born Jan. 7, 1638. From 1640 to 1680, his fellow Jesuit Athanasius Kircher amassed a huge collection of curiosities and mirabilia, which he housed in a large room in the Collegio Romano, the university run by the Society of Jesus in Rome. Kircher was so busy writing encyclopedia after encyclopedia that he never got around to compiling a catalog of his collection (the second of the rotating images on the Library’s home page displays a portrait of Kircher and one of his massive tomes). When Kircher died in 1680, his collection remained at the Collegio Romano, but entropy slowly took over and objects began to wander about and disappear. Finally, the College asked Buonanni to take on the project of publishing a catalogue of the Kircher collection. Buonanni was an unusual choice for this task, for while he was interested in natural history, he had no training in the sciences–he basically taught Aristotelian philosophy. He did collect shells, and his first published work (1681) described and illustrated his shell collection. Unfortunately, the hundreds of images on the 50 plates bore no resemblance whatsoever to the shells they were supposed to represent, which did not bode well for the Kircher cataloguing project.

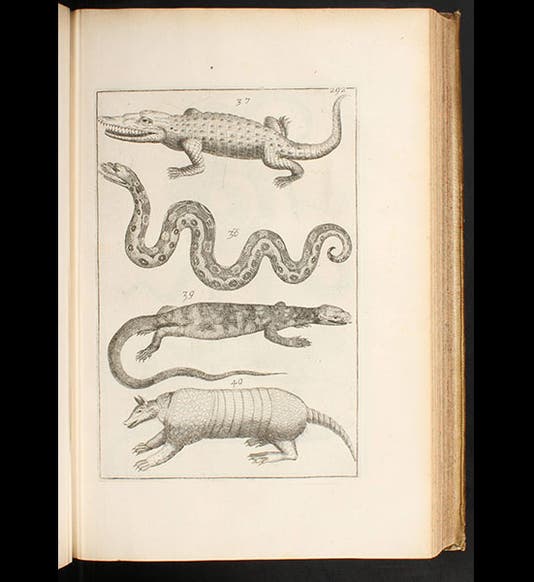

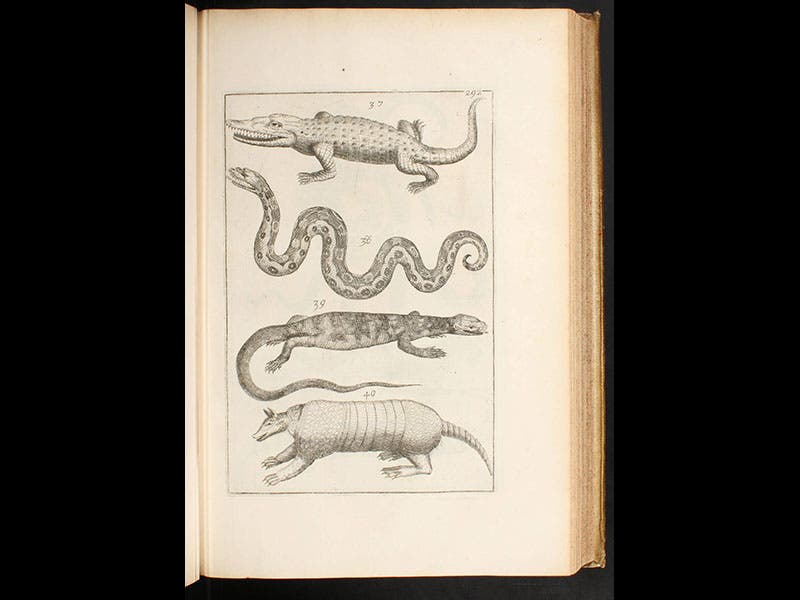

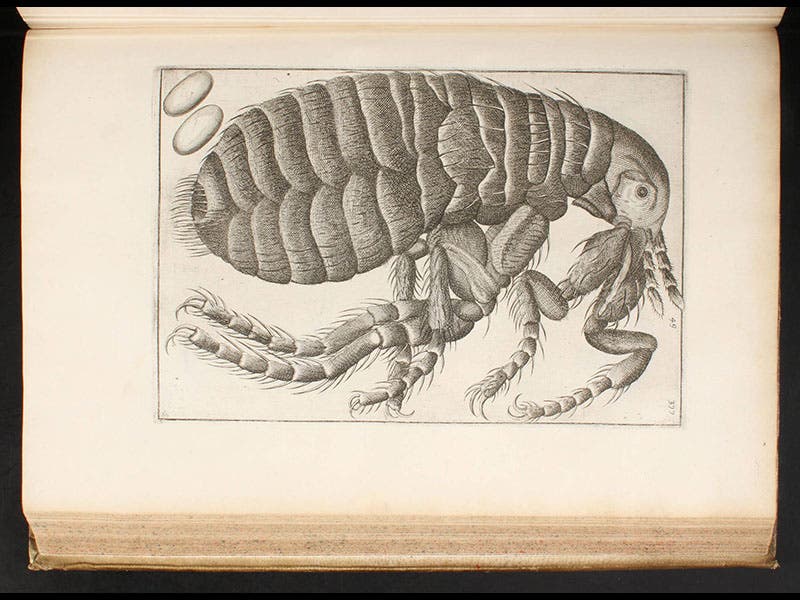

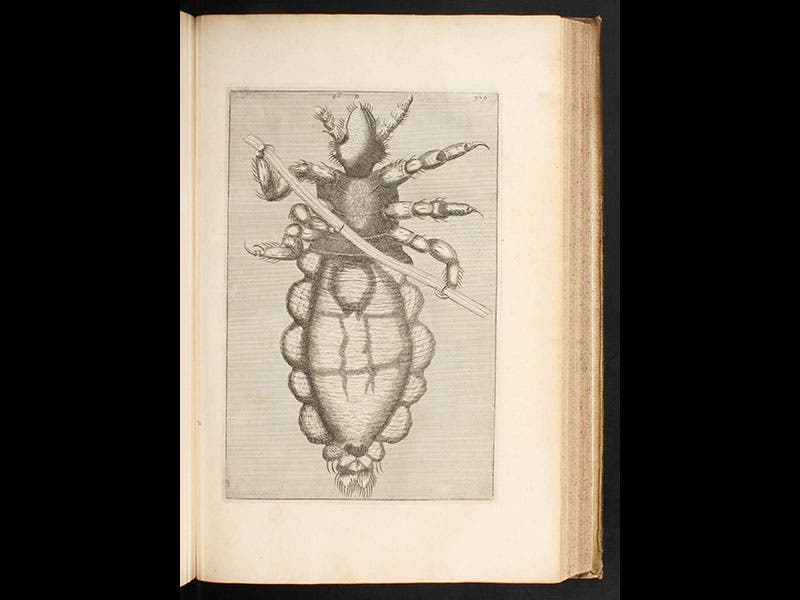

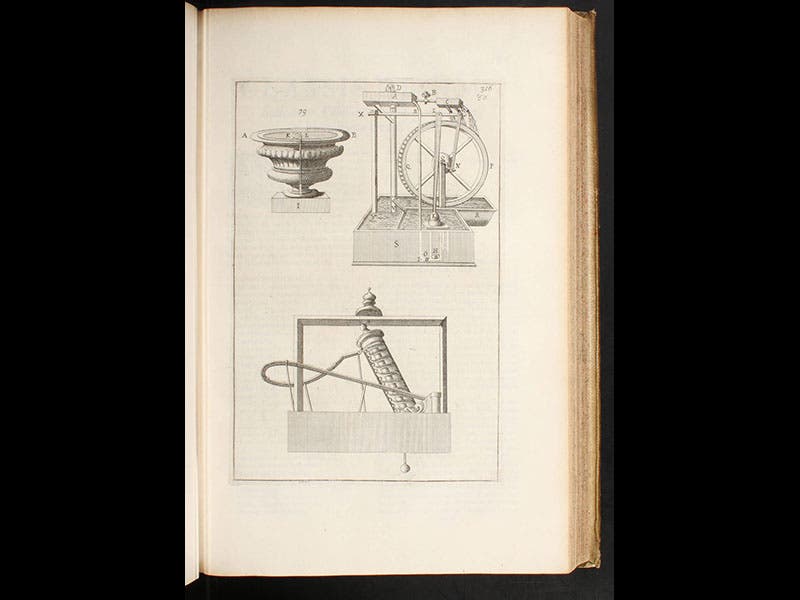

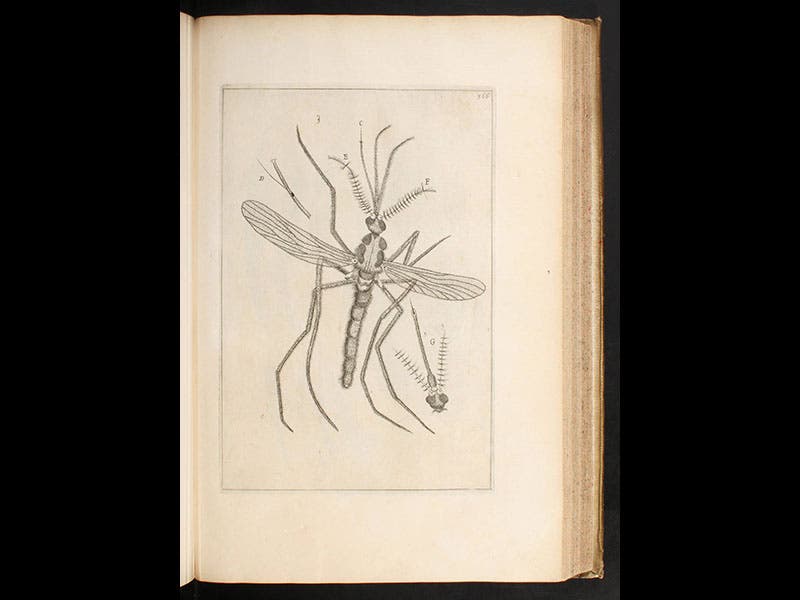

But Buonnani took his assignment seriously, and after ten years work, he published the Musaeum Kircherianum (1709), a massive folio that listed all of the objects in the collection and supposedly illustrated many of them. The trouble is, rather than commissioning new engravings of the actual objects in Kircher’s collection, Buonanni found it easier to borrow already existing illustrations of objects in other people’s collections. So the images of the chameleon and crocodile in Kircher’s museum (first image) were actually taken from Basil Besler’s catalogue of his Nuremberg museum; Buonanni’s pictures of a flea and a louse (second and third images) were blatantly purloined from Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665); his illustrations of perpetual motion machines had their origins in the books on machines by his fellow Jesuit Gaspar Schott (fourth image); and his mosquito is identical to that used by Jan Swammerdam’s (fifth image). The only certifiably original illustrations in the entire volume are the ones that accompany the section on shells, for which he relied on his earlier shell book. But since those illustrations did not depict real shells, this was not really an improvement.

We should not be too hard on Buonanni; there were other collectors who published catalogues of their own collections but used images borrowed from other catalogues. But Buonanni did raise the bar of permissible plagiarism to a much higher level.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.