Scientist of the Day - Frances Oldham Kelsey

Frances Oldham Kelsey, a Canadian/American pharmacologist and physician, died Aug. 7, 2015, at the age of 101. She had been born in Cobble Hill, British Columbia, in 1914. She studied at Victoria College, and moved to McGill for her master’s in pharmacology. She was then accepted into the pharmacology program at the University of Chicago, where she received her PhD in 1938. While working for her degree, she began consulting for the FDA, with whom she would become more and more involved as her career progressed.

Frances Oldham, as she was then, joined the faculty at Chicago after receiving her degree, and married a fellow faculty member in 1943, becoming Frances Kelsey. She received her M.D. from Chicago in 1950. For reasons unknown to me, the couple moved in 1954 to the University of South Dakota, certainly not a step up, career-wise. She resigned 3 years later. It does not yet sound like a success story in the making.

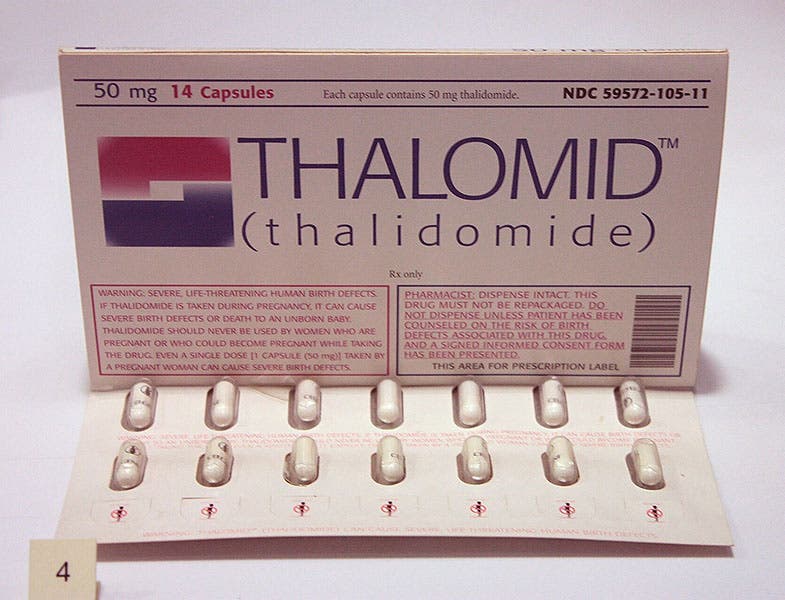

But in 1960, she was hired by the FDA in Maryland to review applications for approval of new drugs. One month into her new job, she was asked to consider an application by Richardson-Merrell for approval for a drug they called Kevadon, to be used as a sedative, anti-emetic, and morning-sickness suppressor. The active drug in Kevadon was thalidomide, patented and marketed by Chemie Grünenthal GmbH in Germany. It had been approved for use in most of Europe, and in Canada, and Richardson-Merrell expected rapid approval in the U.S. But Kelsey noticed that no scientific evidence of its effectiveness was offered with the application, nor had its safety been demonstrated, nor had there been any clinical trials involving humans. She rejected the application and called for clinical trials.

Instead of beginning trials, Richardson-Merrell waited the requisite 60 days and resubmitted the application. Kelsey again denied approval, and did so every 2 months for a full year. Big Pharma (the term had not yet been invented, but seems appropriate here) was not happy and complained to Kelsey’s superiors, but they backed Kelsey, and she stood her ground – no clinical trials, no approval.

It could, and probably would, have gotten nastier, but by 1961, the need for testing was becoming less critical, as reports accumulated from Europe, especially Germany, of birth defects in newborns whose mothers had taken thalidomide while pregnant. Babies born to such mothers often had missing or deformed limbs. The number of “thalidomide babies” grew to 10,000, mostly in Germany and England, and that does not count the many more that were stillborn. By spring of 1962, the German manufacturer withdrew thalidomide from the market. Because Kelsey refused to budge, the number of deformed births in the United States was somewhere between 17 and 40, almost all traceable to capsules distributed by Richardson-Merrell to physicians in advance of the approval that never came.

When the story broke as front-page news in the summer of 1962, Frances Kelsey was acclaimed as a hero, and indeed, she was. President Kennedy awarded her the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service in August of 1962 (fourth image). Later that year, when legislation was enacted to crack down on pharmaceutical companies and their methods of testing new drugs, President Kennedy invited Frances Kelsey to the bill signing (first image).

Kelsey spent the rest of her career with the FDA, usually in leadership positions created especially for her. She finally retired in 2004, when she was 90! She was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls in 2000. Our last photograph was taken on that occasion.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.