Scientist of the Day - Francis Leopold McClintock

Francis Leopold McClintock, a British naval officer, was born July 8, 1819. McClintock took part in four separate voyages to the Arctic between 1848 and 1859 in search of John Franklin’s lost Arctic expedition, not heard from since 1845. McClintock (sometimes spelled M’Clintock) was second in command of HMS Assistance, as part of the Austin expedition of 1850-51, when he undertook a heroic trek on foot. In the spring of 1851, while his ship was frozen in the ice, McClintock and six men set out pulling a 1200 pound sledge, looking for Franklin’s ships. They returned July 4, having travelled 760 miles in 80 days, in conditions of high wind and low temperatures (thirty below) that would send us scurrying for warmth in minutes. It was one of the epic sledge journeys of the era. They did not find Franklin then, but they did find “Parry Rock”, a large chunk of sandstone that had been carved with an inscription by Edward Parry during his stay at Winter Harbor in the Arctic Archipelago in 1820. They were the first Europeans to see the rock since it was inscribed. You can see an illustration of Parry’s rock, as recorded by McClintock, in our online exhibition, Ice: a Victorian Romance (2008), as item 40.

McClintock was also commander of HMS Intrepid as part of the Arctic Squadron of 1852-54, commanded by Edward Belcher, when Belcher abandoned four of the ships to the ice and left them there, over McClintock’s adamant protests.

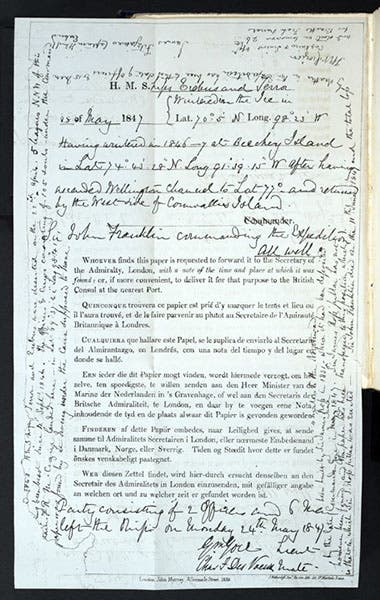

The Admiralty gave up its Franklin searches in 1855, after John Rae obtained trinkets and learned from the Inuit that Franklin’s crew had trekked to their deaths years ago. But Lady Jane Franklin refused to be presumed a widow, and in 1857, she sponsored one last voyage to search for her husband. McClintock commanded this expedition in the steamer yacht Fox. The Fox expedition finally confirmed the death of Franklin, as McClintock found material remains, such as silverware, and most significantly, in May of 1859, a document on King William’s Land, recording that the ships had been abandoned north of the island and that Franklin had died.

McClintock returned to England and immediately published Narrative of the Discovery of the Fate of Sir John Franklin and His Companions, often referred to (as we do here) by the subtitle: The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ in the Arctic Seas (third image). It appeared in November of 1859, just six months after the document attesting to the fate of Franklin was discovered. The book promised to be such a best-seller that lending-library impresario Charles Mudie reserved 3000 copies of the book for Mudie’s Lending Library (simultaneously reserving, from the same publisher, 500 copies of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, published that same month).

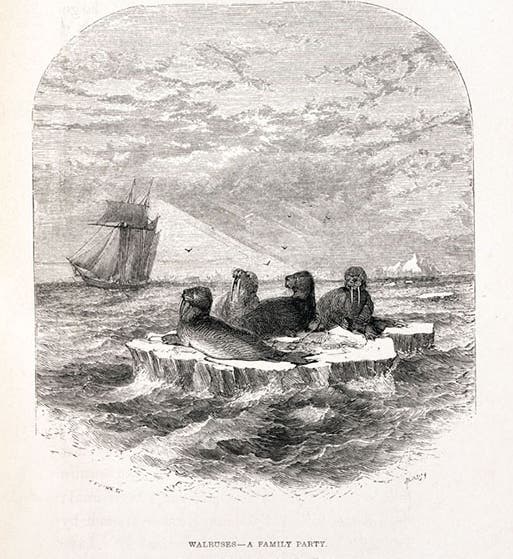

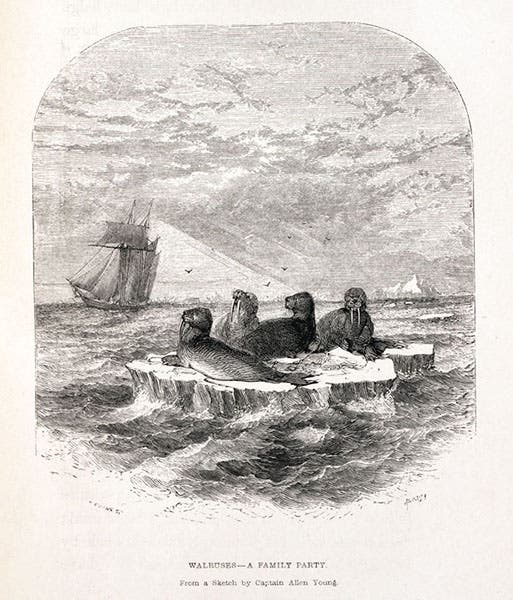

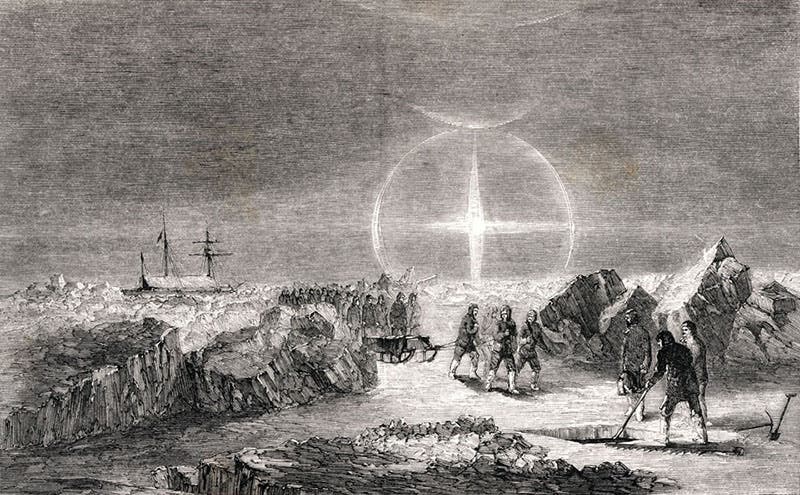

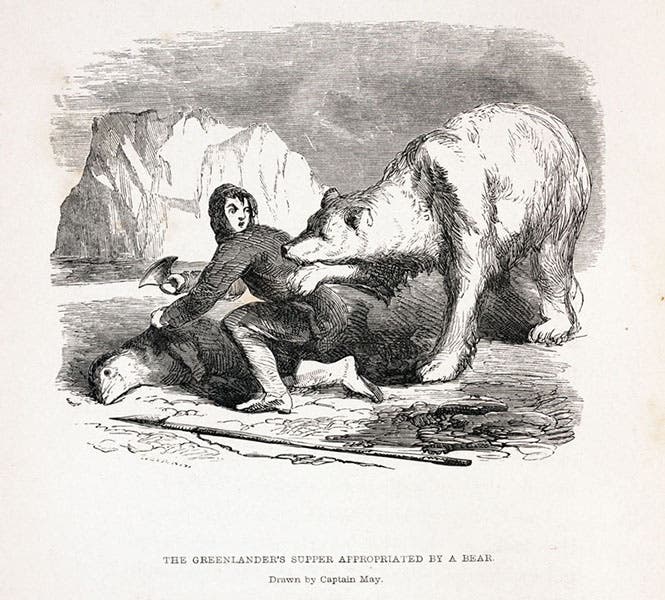

One of the attractive features of The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ is a series of illustrations that depict the mundane events of Arctic life: steaming out of an ice pack, losing one’s dinner to a polar bear, spotting an ice floe strewn with walruses, and burying a sea-mate. We reproduce a few of those here. The book also includes a large folding lithographed facsimile of the hand-annotated document that recorded the abandonment of the ships and the death of Franklin (sixth image). And finally, the book was decorated with an embossed cloth binding, with a gold-stamped image of the Fox on the cover. We include that as well (eighth image).

Stephen Pearce, the official painter of portraits of Arctic voyagers for the Admiralty, did several portraits of McClintock, which you can find in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Most show him in dress blues; we like the one here, that depicts him in a parka, suited up for a sledge expedition (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.