Scientist of the Day - Francis Maitland Balfour

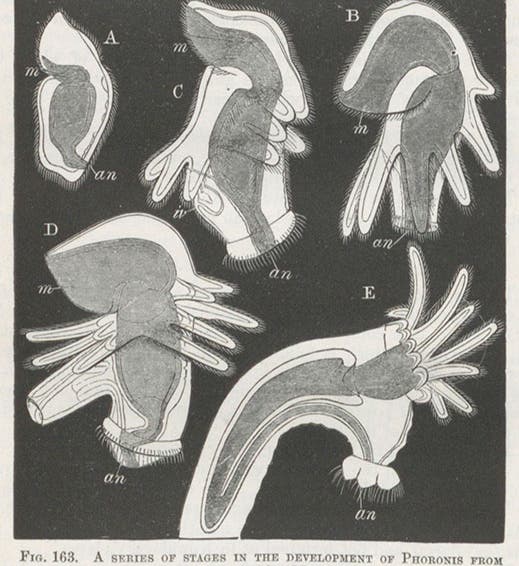

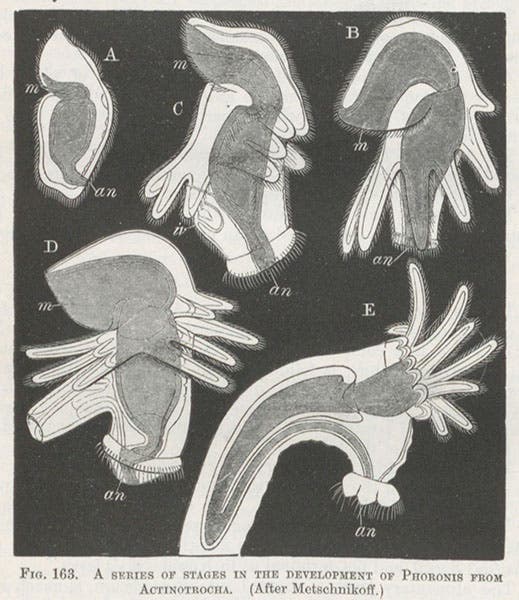

Fives stages in the development of the larva of Phoronis, a horseshoe worm, wood-engraving, in Francis M. Balfour, A Treatise on Comparative Embryology, vol. 1, 1880 (Linda Hall Library)

Francis Maitland Balfour, an English naturalist and biologist, died July 19, 1882. He was born in Edinburgh in 1851 and was not considered to be especially precocious before he enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1870. There he discovered comparative morphology, the study of forms in organisms. After hearing a series of lectures from Michael Foster, the eminent Cambridge physiologist speaking on embryology, Balfour’s focus narrowed to the morphology of embryos and larvae. In 1872, Anton Dohrn, a German vertebrate embryologist, founded a research institute in Naples, later to be called the Naples Zoological Station, and Balfour won one of the first appointments there. When he returned to Cambridge in 1874, he was elected to Trinity College as a Fellow, and he began at once an intense research program into embryological form and development. This meant: a) mastering all the literature on the subject in half-a-dozen languages, such as the German works of Ernst Haeckel, and then: b) undertaking his own embryological research to fill in the many holes in the then current understanding of the origins of organic forms.

Portrait of Francis M. Balfour, frontispiece, The Works of Francis Maitland Balfour, 4 vols., ed. by Michael Foster and Adam Sedgwick, vol. 1, 1885 (Linda Hall Library)

The outcome was a prodigious two-volume work, published in 1880-81, called A Treatise on Comparative Embryology. The first volume dealt with invertebrate embryology, the second with vertebrates. Since we could not scan it all at once, I chose some pages from volume one – invertebrates - to include here. I know very little about embryology, vertebrate or invertebrate. But I do know how to tell when someone knows what he is talking about. I dipped into half a dozen sections, and it was quite clear that Balfour knew the state of studies of whatever organism he was discussing (he cited his predecessors and colleagues freely), and also that he had a lot of original observations of his own to contribute. He drew his illustrations from the best sources available (telling us what those were), and in many cases used images of his own. All the illustrations were wood-engraved in a uniform style, as if by one engraver, but the wood-engraver was not named, which was my only disappointment in this study. It is evident that, whoever this was, he was a great admirer of Henry Vandyke Carter, who illustrated the famous Gray's Anatomy of 1859, and revolutionized anatomical illustration with his simplified drawings and clear labeling method.

Title page, Francis M. Balfour, A Treatise on Comparative Embryology, vol. 1, 1880 (Linda Hall Library)

One of the images we include shows the development of the larvae of Phoronis, the horseshoe worm (first image). It had been thought that the larva was an independent organism, and it even had its own name: Actinotroch. Balfour knew differently, as his caption shows. In a matter of hours, the actinotroch grows new tentacles; turns its gut inside out, bending it into a horseshoe shape; and bodily switches ends, its front end becoming its rear end. I don't think Balfour discovered all this, but he certainly understood it. The image is a particularly good example of the Carter style of anatomical illustration, especially in the placement of the labels.

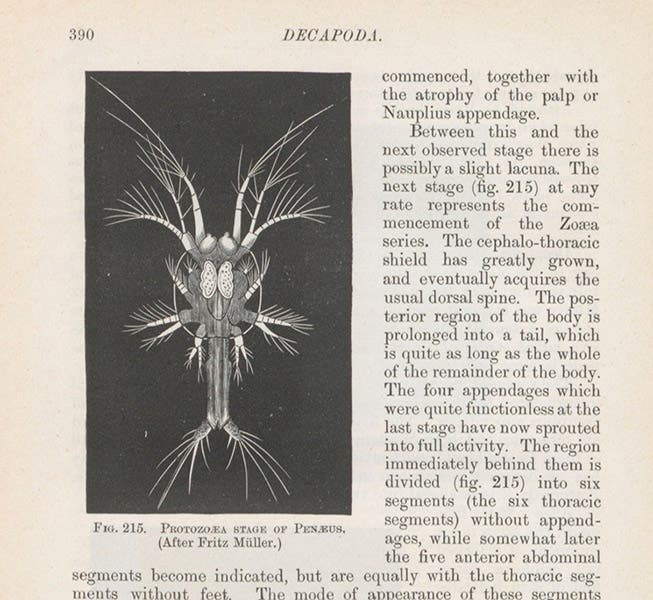

A stage in the development of the larva of Penaeus, a prawn, wood engraving, in Francis M. Balfour, A Treatise on Comparative Embryology, vol. 1, 1880 (Linda Hall Library)

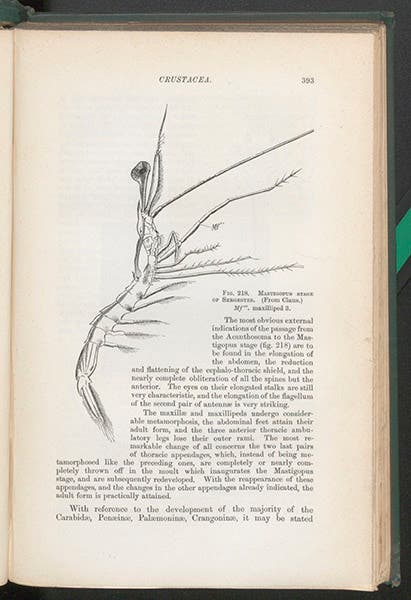

Our other images show the larval stages of other invertebrates, identified in the captions. For one of those (Penaeus, a prawn, fourth image), we include a little of the text alongside the image. One should understand that Balfour was an evolutionary morphologist, which means he understood that larval development is forged by natural selection. The image of Penaeus, incidentally, which Balfour says he took from Fritz Müller, is in a different style from the others, with no labels at all.

Larva of Sergestes, another prawn, line-engraving, Francis M. Balfour, A Treatise on Comparative Embryology, vol. 1, 1880 (Linda Hall Library)

I provide these details from Balfour's first book as evidence that this was a researcher on the way up. Not yet 28 years old when he finished the manuscript, he demonstrated an insight, understanding, and dedication that made the research universities of those days (Cambridge, Oxford, Edinburgh, University College London) salivate in anticipation. Several of these institutions made him offers, but he elected to stay at Trinity, which established a new chair just for him, Professor of Animal Morphology. Balfour was likely to be the next great exponent of Darwinism in England, following the path of Thomas H. Huxley. Huxley saw Balfour that way, and so did Darwin.

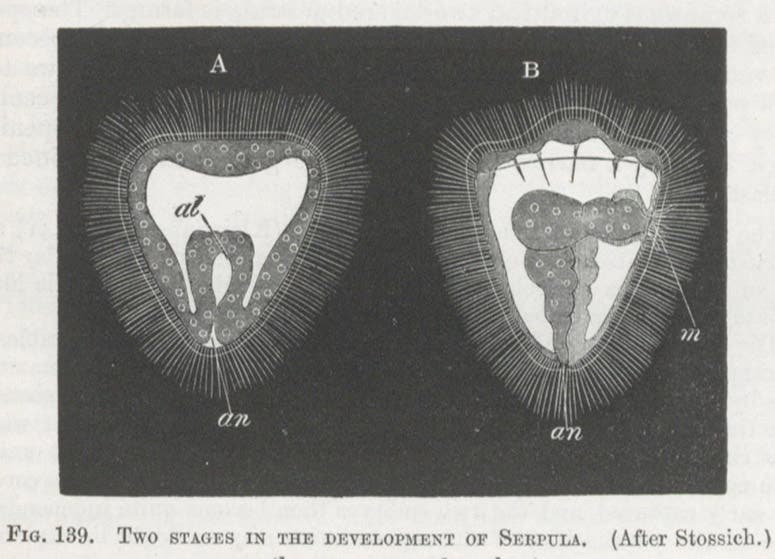

Two stages in the development of Serpula, a plumed tubeworm, wood-engraving, in Francis M. Balfour, A Treatise on Comparative Embryology, vol. 1, 1880 (Linda Hall Library)

But fortune can be brutal. Like many Victorian scientists (John Tyndall comes to mind), Balfour was an ardent mountain climber, and in mid-summer of 1882, he set out with a guide to climb the Aiguille Blanche, a peak on the Mont Blanc massif that had not yet been scaled. On this day in 1882, Balfour and his guide died on the mountain, apparently from a fall. Balfour was 30 years old, and had yet to give his first lecture at Trinity in his new chair.

The British scientific community was devastated, especially Huxley, who lost his most likely successor. Since Huxley, 25 years older than Balfour, survived him by almost 13 years, he had a lot of time to lament what might have been. Foster, the dean of Cambridge biology, paid his respects with an edition of Balfour’s collected works in four volumes, two of which were the two volumes of Comparative Embryology, but the other two contain all of Balfour’s papers and articles, which can otherwise be hard to find. We have this set in our Library as well. The first volume includes a portrait, I think perhaps the only portrait of Balfour that survives. We show it as our second image.

Balfour’s older brother, Arthur James Balfour. was prime minister of England for three years, 1902-05; he lived to be 82, dying in 1930. His older sister Evelyn married the scientist John William Strutt, Lord Rayleigh, who discovered argon, and she lived to age 88, dying in 1934. It is painful to think what Francis might have accomplished, had he been allowed to share the long lives of his siblings.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.