Scientist of the Day - Frederic A. Lucas

Frederic Augustus Lucas, an American taxidermist, osteologist, and popular science writer, died Feb. 9, 1929, at age 76. He was born on Mar. 25, 1852. His father was a ship’s captain, so Lucas went to sea as a lad, and he was the veteran of two long voyages and several shorter ones by the time he was 18. One of his uncles was a taxidermist, so Lucas decided to learn that trade, and he got a job in 1871 at Ward's Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, New York, and he worked there until 1882, learning comparative anatomy, osteology, taxidermy, and such mundane things as how to pack mounted specimens for shipments to museums around the world. Ward's was a great training center for dozens of future naturalists, who avoided the academic route to their profession and instead learned by experience.

After eleven years at Ward’s, Lucas was as well qualified for museum work as any graduate of Penn or Harvard, and he was hired by the U.S. National Museum (later part of the Smithsonian Institution) as a specimen preparator. He then rose to assistant curator of comparative anatomy, then curator. He moved on in 1904 to become curator in chief of the Brooklyn Museum, and then, in 1911, he was appointed Director of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, probably the plum science museum directorship in North America. That was quite a career path for an unlettered bone-cleaner from Ward's!

Lucas was a pioneer in the United States of popular books for the general public on prehistoric life. The genre began in England, with the works of Henry N. Hutchinson, who published Extinct Monsters (1892), and Creatures of Other Days (1894), with illustrations by Cecil Aldin. Lucas decided to write a similar kind of book, focusing on the prehistoric animals of North America, and for an illustrator, he had in his stable the young Charles Knight, who was just coming onto the scene, providing drawings for the U.S. National Museum and the American Museum of Natural History.

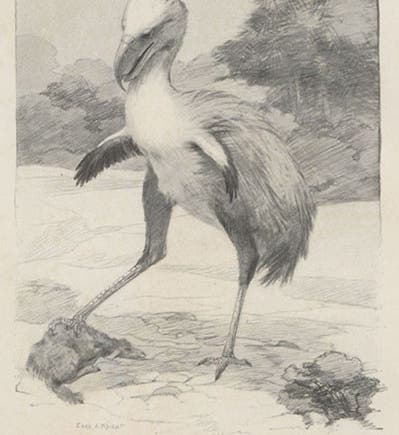

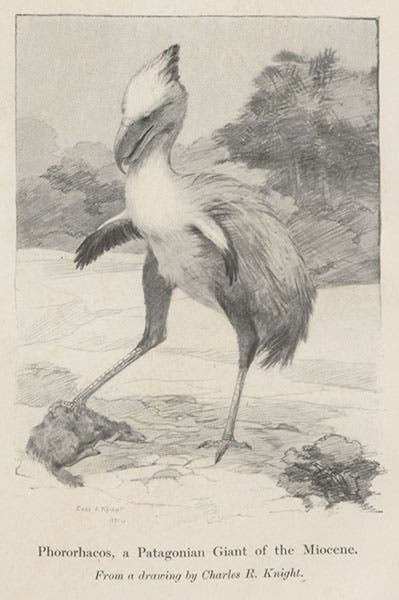

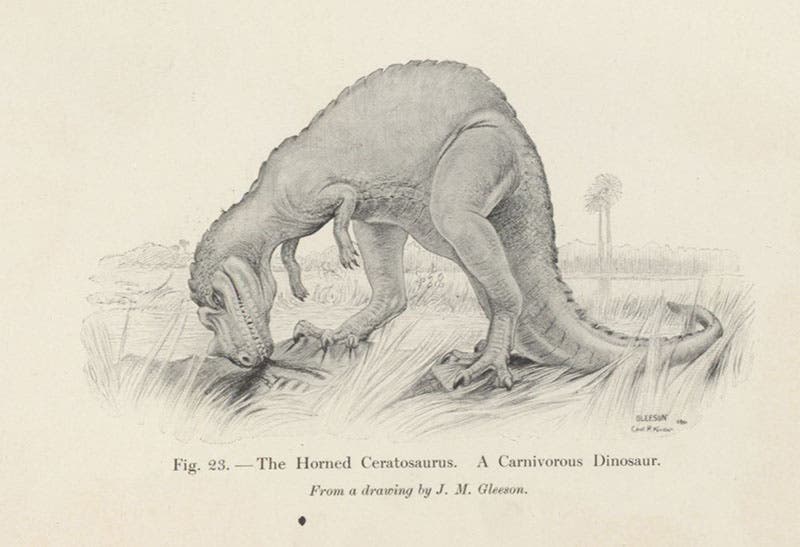

Lucas’s first book of this type was Animals of the Past (1901), published while he was a curator at the National Museum. It is a very well-written and informative book, telling the reader how fossils form, what life in ancient seas were like, and then providing several chapters on dinosaurs, since any curator in 1901 knew that that was what the public wanted to see. He explained that restoration is of great importance, and that drawings of those restorations were of equal importance, stressing the excellence of Charles Knight and his assistant, J.M. Gleeson. The book contains 41 illustrations, many of which are full page black-and-white plates, with just as many wood engravings in the text. We show you several of those here, including the book’s frontispiece, depicting a large predatory bird from south America, drawn by Knight (first image); a Ceratosaurus dinosaur, drawn by Gleeson (fourth image), and a two-page diagram depicting the evolution of the horse (fifth image).

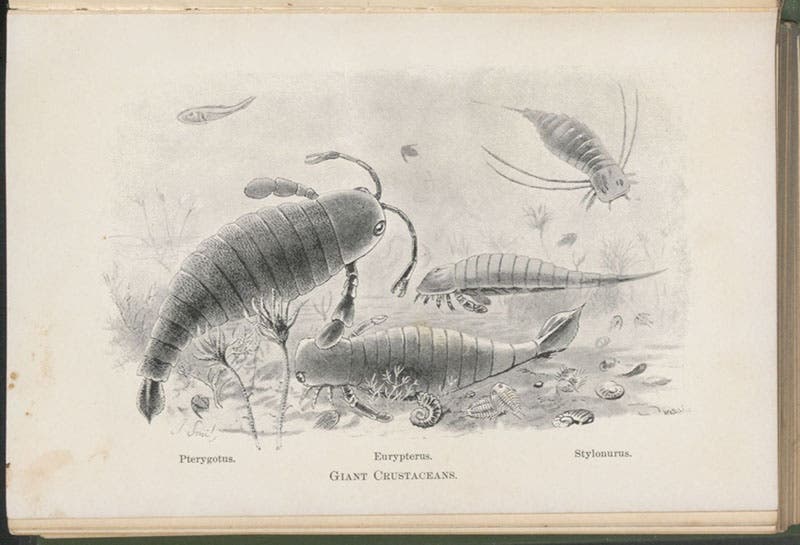

The very next year, Lucas published Animals before Man in North America (1902). It is very similar in content to Animals of the Past, so it is not clear if Lucas had a different audience in mind, or was just capitalizing on the success of his first book. It does have a different set of illustrations, some by Knight and Gleeson, but many were borrowed from Hutchinson’s Creatures of Other Days, which means they were done by Aldin. Lucas does not tell us why he went to England for some of his images; perhaps he did not have to pay for them, or perhaps American artists were not interested in pre-dinosaur life, as Aldin was. But Animals before Man was and is a most attractive and readable book. We show here the frontispiece, a Triceratops, by Knight (seventh image); some Paleozoic eurypterids, by Aldin (eighth image); an American mastodon, by Gleeson (ninth image), and a photograph of a Triceratops skull in the U.S. National Museum (tenth image).

Both of Lucas’s popular science books were publishing successes. Each went through 7 editions in Lucas’s lifetime, and for a short while, new editions were coming out every year. So clearly it filled an important niche for the reading public. Competitors soon appeared, such as Henry Knipe’s From Nebula to Man (1905) and Evolution in the Past (1912), with illustrations by Alice Woodward. But these were more elaborate (and thus more expensive) books, and were less clearly written than those by Lucas.

Lucas also had social concerns. He was worried about the extinction of animals such as the great auk, and fearful that animals such as the fur seal would follow the auk into oblivion. He was so worried that he accepted an appointment in 1896 to the Fur Seal Commission that was formed to regulate the fur seal industry. This seems to be worthy subject matter for a second post on Lucas, at some time in the near future.

I could find no portrait of Lucas as a younger man. There must be one somewhere in the archives of the Smithsonian Institution or the American Museum of Natural History, but if so, they do not turn up in an online search.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.