Scientist of the Day - Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, a German astronomer, was born July 22, 1784, in Minden, Westphalia. He was very good at mathematics but never went to a university, instead entering the world of commerce as a young man and being trained there. He was interested in astronomy and could do all the calculations, so he came to the attention of Heinrich Olbers, a well-respected astronomer in Bremen, and through him, to Johann Schroeter, who took him on as an assistant at his observatory at Lilienthal. For Schroeter, Bessel reduced (turned into useable tables) all the observations of James Bradley, the Astronomer Royal of England in the 1740s. That was an impressive feat for someone untrained in astronomy. We have that publication (1818) in our collections.

Probably because of this, King Frederick William II of Prussia decided to appoint young Bessel as director of the new observatory at Königsberg up on the Baltic. I am sure the academics at the university took this very badly, since Bessel had no degree, but Bessel was up to the challenge, and continued as director until his death in 1846.

Besse's most significant contribution to astronomy came in 1838, when he measured the parallax (slight annual change in position) of a star, 61 Cygni, which no one had been able to do for any star before. If you know the parallax of a star, you can calculate its distance, making Bessel the first person to measure the distance to a star. We told the story of Bessel and 61 Cygni in a post long ago, in 2015, a post in which we provided no details of Bessel’s life before 1838, which is why we have included some of that here. Fortunately, we can justify a second post on Bessel, because he made another very important astronomical discovery in 1844 (actually, a pair of discoveries) which would have been the capstone of anyone else's career. So we tell that story today.

Sometime around 1840, Königsberg Observatory received a new meridian circle, a telescope that swings through a vertical circular arc and can record very accurate positions of stars, because there is almost no stress on the instrument to cause distortion. I tried to find an image of the Königsberg meridian instrument, made by Adolf and Georg Repsold, but could not, and since the observatory was destroyed in World War II, there are no modern photos. But I wrote a post once on Edward Troughton, who built a meridian circle for Greenwich Observatory, and there are some images there of the Greenwich circle, which probably was not much different from Bessel's instrument in Königsberg.

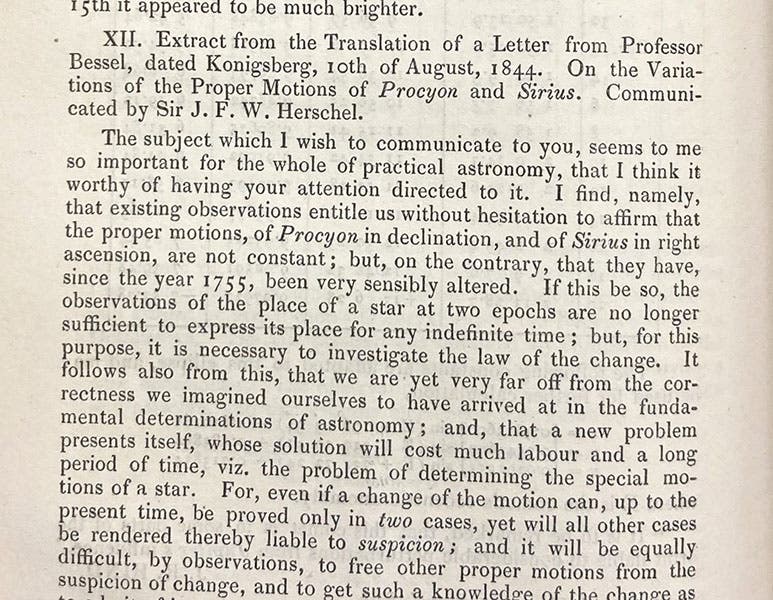

In 1844, Bessel was measuring the proper motion of Sirius, the bright star in Canis major, as he had done many times before, and he noticed that it had a wobble – a very tiny wobble, but a wobble nevertheless. Moreover, the wobble was cyclical. He noticed the same was true for Procyon, the other “Dog Star,” in nearby Canis minor. The only thing Bessel could think of that could make a star shift back and forth in position was a companion star or a very large planet. Bessel could find no visible companion for either Sirius or Procyon. So he postulated their existence. Moreover, since they must be tiny to be invisible, but massive enough to gravitationally affect the parent star, these must be very dense objects, unlike anything known to exist at that time. A paper summarizing Bessel’s thoughts on Sirius B and Procyon B (as we now call them) appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1844, in the form of a letter to John Herschel (fourth image).

Eighteen years later, Alvin Graham Clark, one of the sons in “Alvan Clark and Sons,” a telescope-making firm in Cambridge, Mass., was testing a new pair of 18.5-inch lenses that the firm had made for the University of Mississippi, before the Civil War cut the lines of commerce. Clark chose Sirius as a test target, and he saw the tiny companion star, Sirius B, right next to Sirius. No one else could see it, until more Clark refractors were built and distributed to observatories worldwide. Procyon B was not spotted until 1896 (using a Clark refractor at Lick Observatory), and not until 1910 would Sirius B be recognized as a new kind of stellar object – a white dwarf star, a tiny but massive star that is a byproduct of stellar evolution (it would later be discovered). So you can decide who discovered Sirius B – Clark, when he was the first to see it in 1862, or Bessel, who predicted its existence in 1844.

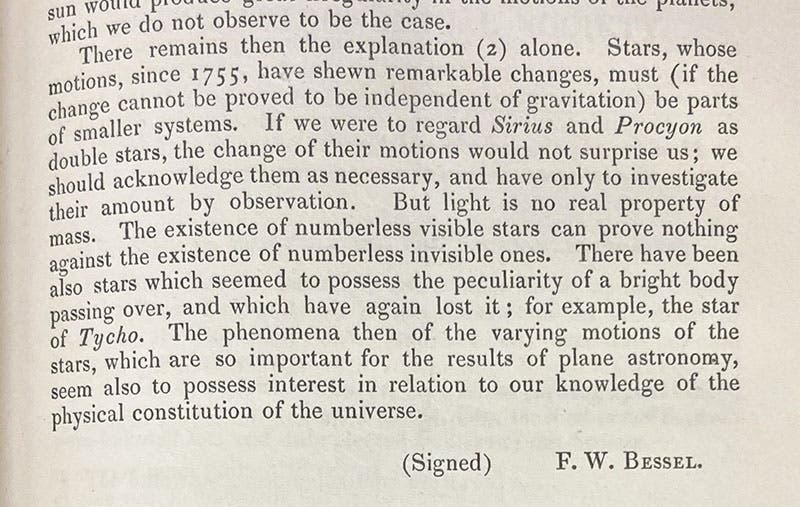

Bessel’s conclusion to his letter to Heschel in 1844 (fifth image) shows clearly that Bessel understood what was happening. He was opening up a new kind of astronomy �– an astronomy of the invisible – whereby observations made of visible objects can tell us about objects that we cannot see. Astronomers do that a lot these days.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.