Scientist of the Day - Gabriele Beati

Gabriele Beati, an Italian Jesuit mathematician, was born in 1607 and died in 1673. We do not know the date of his birth. Born in Bologna, he entered the Society of Jesus when he was 20 years old. He must have demonstrated considerable aptitude for both mathematics and theology, for he soon found himself teaching both subjects at the Collegio Romano, the flagship Jesuit university in Rome. We will leap forward to 1662, when he published a modest treatise on cosmology, Sphaera triplex, artificialis, elementaris, ac caelestis; it is the only book by Beati that we hold in the Library. The Shaera triplex is another in a long line of treatises on the sphere, going back to Sacrobosco in the 13th century. The three spheres are the armillary and its various circles; the world of the elements; and the celestial sphere of planets and stars.

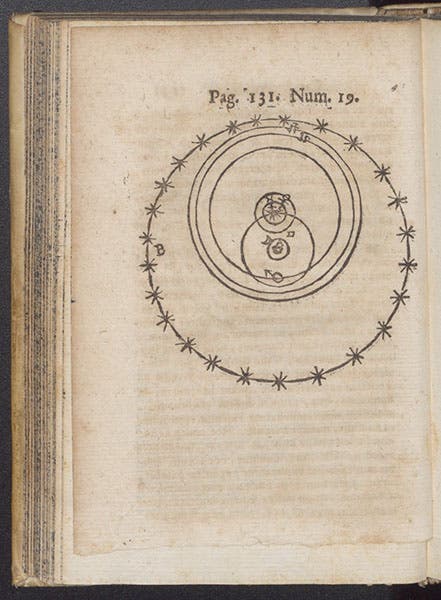

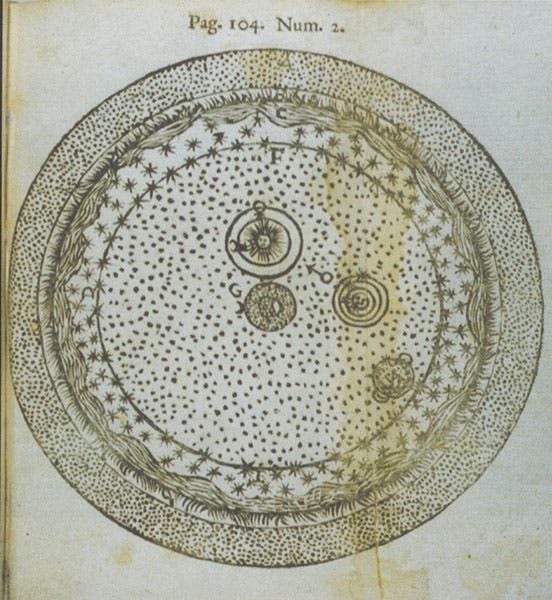

Nearly every one of the hundreds of published Sphaerae contain a cosmological diagram. You can see on in our entry on Christoph Clavius, an earlier Jesuit mathematician. Typically, it is just that, a mathematical diagram of nested circles, with no intention of showing the physical cosmos. Indeed, Beati’s work contains quite a few such diagrams; we show the page that diagrams the Tychonic cosmology below (third image, below), and there are similar diagrams for other cosmological systems, such as those of Copernicus and Ptolemy.

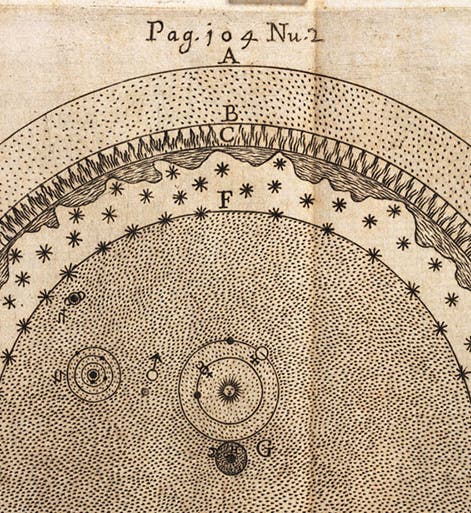

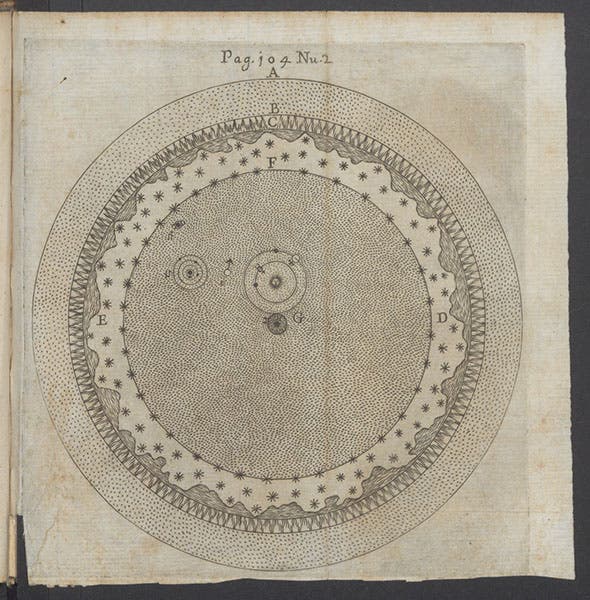

But Beati’s Sphaera triplex has an additional plate that is without precedent. It is not a woodcut but a large engraving, and it depicts the physical cosmos. We see the complete engraving in our fourth image (just below), a detail of the top half in our opening image, and a super-detail of just the planetary region in our fifth image.

The most striking feature of the engraving is that the planets float free. In nearly all preceding cosmological diagrams, the planets are attached to circles, which represent the sections of spheres. However, in Beati’s engraving, there are no planetary spheres. There is a sphere for the firmament, and a sphere that bounds the elementary region at the center, and a sphere for the empyrean heavens above the firmament. But for the planets, there are no spheres. They seem to float in a fluid heavens.

Planetary spheres had been a mainstay of cosmology until Tycho Brahe, who around 1588 proposed a cosmology in which the orbits of Mars and the Sun intersected, proving, to Tycho, that there can be no physical spheres. The planets must move about in a fluid medium. Jesuit mathematicians up until about 1620 generally followed the cosmology of Aristotle and the astronomy of Ptolemy, but then they began to switch over to the Tychonic system, because it had most of the advantages of the Copernican system but retained a central and stationary Earth. Sometimes the Tychonic system was modified, as was the case with Giovanni Battista Riccioli in his Almagestum novum (1651). Riccioli was the foremost Jesuit authority on astronomy and cosmology at mid-century, and Beati adopted most of his cosmological viewpoints. But Riccioli never provided a picture of the fluid heavens. Beati did, and it is a memorable and unprecedented image.

One of the advantages of removing the circles is that now the image can illustrate a variety of cosmologies – Copernican, Tychonic, semi-Tychonic (as the Riccioli system was called). In other words, you can draw in your own circles depending on your cosmological preference. Possibly Beati intended this, possibly it was an unexpected result of banishing spheres from the heavens. Also note, especially in our first image, that Beati has unusually carved out space on the outside of the sphere of stars to hold the waters above the firmament, which the account in Genesis assures us are up there. The waters below the firmament now become the interplanetary medium.

One unusual feature of Beati’s book is that it came in two versions – with the fluid heavens depicted as an engraving (our copy), or as a woodcut (copy at the University of Oklahoma Libraries). We show the woodcut version above (sixth image, above). The two prints are not identical – Saturn in particular is differently rendered – but they are otherwise fairly similar. Kerry Magruder at the University of Oklahoma published a thorough study of Beati’s Sphaera triplex some years ago in the journal Centaurus (2009), and he surmised that the first issue contained the woodcut, and that it was replaced with the more elegant engraving in later copies. We are happy to have one of the issues with the engraving. And we are also pleased that it is such a splendid-looking book, inside and out, as you can see (seventh image, above).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.