Scientist of the Day - Georg Bose

Georg Matthias Bose, a German demonstrator of physics, was born Sep. 22, 1710, in Leipzig. Not much is known about his education, but in the mid-1730s, he emerged as a clever demonstrator of physical phenomena, which, after 1735, were primarily electrical effects. He came across the writings of earlier investigators such as Stephen Gray and Charles du Fay, who had discovered such things as electrical repulsion and conduction, and that there are two kinds of electricity. Bose sought to redo their experiments. Unable to procure the electrical tubes used by Gray and Dufay, which would be rubbed to produce electrical effects, Bose fashioned his own spark-producer from a glass vessel, which must have been awkward to rub, but was apparently effective. He could then reproduce all the demonstrations of his predecessors, but he found all that rubbing tedious. Having heard somehow of Francis Hauksbee's electrostatic generator, he mounted his round vessel on an axis and rotated it, and he could now produce electricity in abundance just by rubbing the rotating vessel.

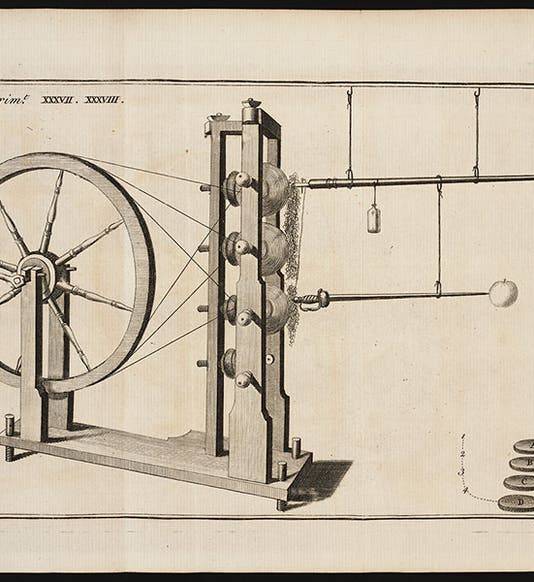

Bose’s most influential experimental moment came when he found a way to free his hands from rubbing the rotating vessel. He hung a gun barrel or an iron rod (both would later be used) from the ceiling by silk threads and allowed a flexible conductor, perhaps a fine chain, to drape from the iron rod onto the rotating glass generator, thereby conducting electricity to the insulated iron. One could now do experiments or demonstrations by simply touching objects to the iron rod while someone else churned the generator. This was a very useful invention – the iron rod came to be called the “prime conductor” and soon every demonstrator was using it. Bose does not illustrate his prime conductor and generator (at least not in any Bose book we have), so we show a 1746 engraving from an article by an English experimenter, William Watson where there are two prime conductors, fashioned from a steel sword and a gun barrel (first image).

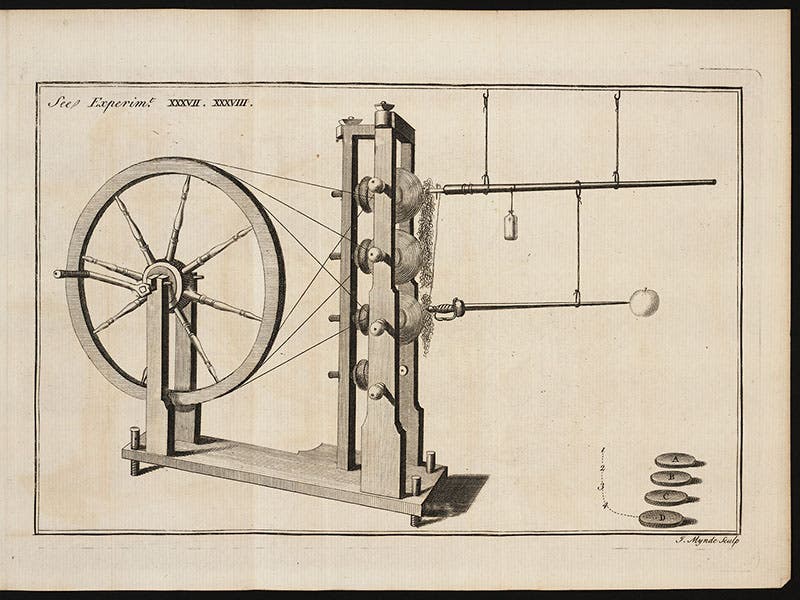

Bose had become a professor at Wittenberg (1738) before his demonstrations got very sophisticated; by the early 1740s, he was well known for his electrical showmanship. Bose was very ingenious in his electrical devising. One popular demonstration was the Venus electrificata, where a young woman stood on an insulating wax disc and laid her hand on the prime conductor. When a man tried to kiss her, the effect was memorable. Bose described his own attempt to do so and said he nearly broke his teeth. Another demonstration that acquired some notoriety was electrical beautification. A man wearing a special crown sat in a chair beneath a metal disc connected to an electrical generator. Unbeknownst to anyone, the crown had been evacuated to enhance the effects. When the machine was turned on, the crown glowed and sparked. We have an image of such a demonstration from a contemporary, and here from a secondary source (second image)

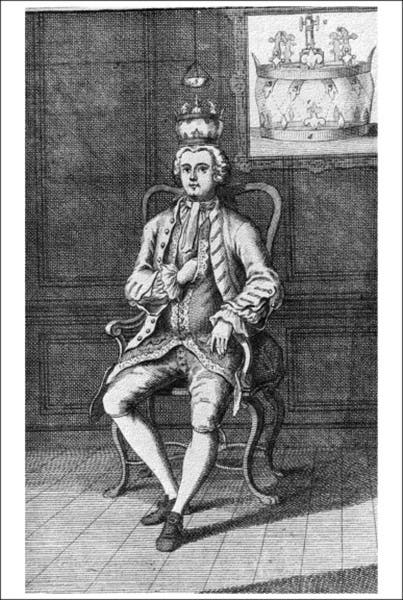

Bose published two books on electricity, Tentamina electrica (1744) and Recherches sur la cause et sur la veritable téorie de l'électricite (1745). We have the latter work in our collections (third image). It is unillustrated, which is why we have had to turn to other sources for our images. But two features of his book are of interest, at least to me. One is that the book is dedicated to the fellows of the Royal Society of London and not, say, the academy of science in Berlin (fourth image, above). One wonders why.

The other intriguing piece of text is the introductory quotation (fifth image, above), just opposite the dedication page. It is from a work by Seneca, De vita beata (On a happy life). I will not repeat the Latin verse here, since you can read it in the illustration, but I will provide a translation (the Loeb Library translation):

I have made every effort to remove myself from the multitude and to make myself noteworthy by reason of some endowment. What have I accomplished save to expose myself to the darts of malice and show it where it can sting me?

This perhaps answers the question as to why Bose was reaching across the channel to London – he doesn't seem very happy with the treatment he received from his electrical competitors in Wittenberg and Leipzig. Perhaps it also explains why he published his second work in French rather than German.

There is no known portrait of Bose. We acquired our copy of his Recherches from the New England rare book dealer Antiquarian Scientist in 2002. It is a significant member of our collection of “electrical incunabula” – works on electricity published before 1750. There were not many.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.