Scientist of the Day - George Greenough

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

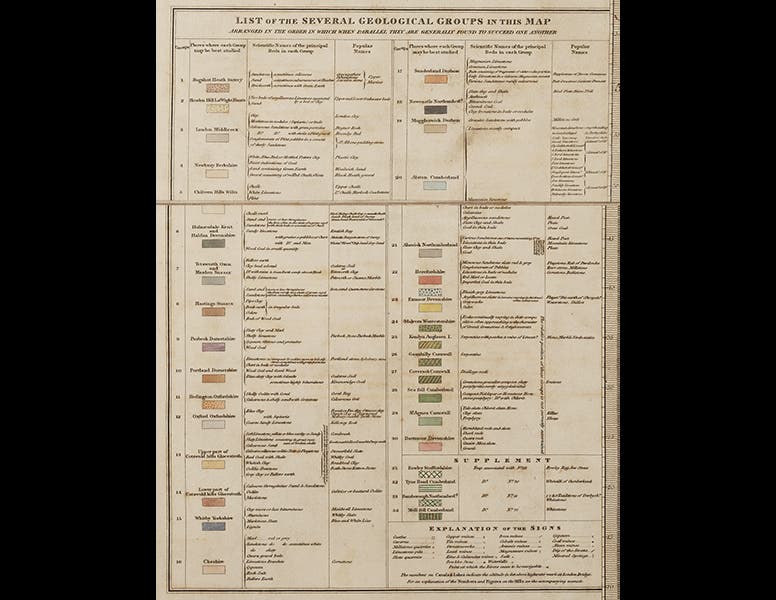

George Bellas Greenough, an English geologist, died Apr. 2, 1855, at age 77. Greenough was one of the founders of the Geological Society of London in 1807 and its first president. Greenough took on his shoulders the task of compiling the Society's first official geological map of Great Britain, using mostly information sent to him by Society members. Only after the project was well underway did the Society discover that an outsider, William Smith, who was not a geologist but a surveyor, was compiling his own map. Moreover, Smith's map was based not on mineralogy, but rather on the revolutionary idea that strata can be better identified by the fossils they contain. Smith published his map in 1815, a milestone in geological mapping, if not THE milestone, but Greenough saw no reason to abandon the Society's projected map, and he continued on, bringing his map to press in 1819 (so says the map) or 1820 (the actual publication date).

The Greenough and Smith maps are both large, very detailed, hand-colored, and splendidly attractive. But because Greenough's map had the official stamp of the Geological Society, it probably dampened the sales of Smith's map, leaving Smith in dire financial straits. What is worse, Greenough's map incorporated a great deal of information that had been borrowed from the Smith map without acknowledgment. The Society and Greenough have taken it on the chin ever since, although Greenough's persistence with his own map is defensible, since he rejected Smith's principle of biostratigraphy, with its basis in fossil evidence. The negative reaction to the ruination of Smith got so bad that, in 1831, to redeem its image, the Society gave Smith a special medal and hung his map in the Society headquarters, right next to Greenough's.

We have copies of the first editions of both the Smith and Greenough geological maps in the History of Science Collection, as well as later editions of both. Greenough's edition of 1865 finally acknowledges its debt to Smith. Our Greenough map is in four sections, each section of 9 prints being mounted on linen and folded to fit in a clamshell box disguised as a moroccan-bound folio. The accompanying Memoir fits in the box as well.

The photos above show: a detail of Oxfordshire, from the Southeast quadrant (first image); the map title, printed on the Northeast quadrant (second image); a detail of London and the Sussex coast from the Southeast quadrant (third image); Cornwall and Devonshire, from the Southwest quadrant (fourth image); a highly magnified view of the area around Penzance in Cornwall (fifth image); and the table below the title that explains the color-coding of the map (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.