Scientist of the Day - George Perkins Marsh

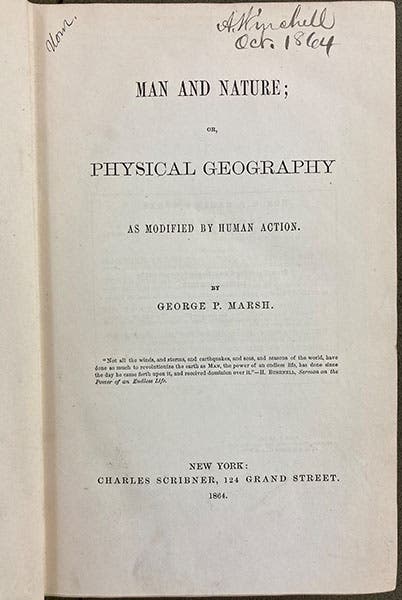

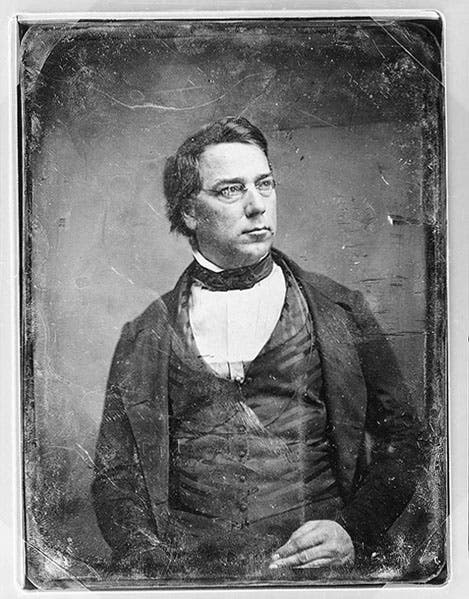

George Perkins Marsh, an American diplomat and scholar, was born Mar. 15, 1801, in Woodstock, Vermont. Marsh is the environmentalist that no one seems to have heard of, the founder of the conservation movement in America, the first person to recognize in print the deleterious impact that humans are having on the Earth, and the author of Man and Nature, or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action (1864), a book as impactful as Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962) in awakening Americans to the dangers of the wanton destruction of habitats caused by human action.

Marsh came from a well-to-do and civically prominent family, attended Dartmouth and then studied law, and served for 6 years in the U.S. House of Representatives (1843-49). He was also an accomplished linguist, eventually conversant in some 20 languages, including some ancient ones in which the opportunities for conversation are limited. He collected art prints of early modern masters, which no one was collecting in the 1840s, and which he could acquire in Europe for very little money. During his time in Congress, he campaigned for a national library (the Library of Congress had a pitiful collection at that time) and wanted to use Robert Smithson's bequest to the United States for that purpose. He was in fact one of the first regents of the Smithsonian Institution, and while he was unable to turn it into a library, he did play a major role in shaping it as a national research institution. He also sold his print collection to the Smithsonian in 1849, their very first acquisition.

From 1849 until his death in 1882, Marsh was a diplomat. He served first as U.S. Minister to Turkey, and then, beginning in 1861, and after a 7-year hiatus in Vermont, as Minister to the new Kingdom of Italy, a position he held until his death. He and his wife travelled widely in both Italy and the Middle East, and he also studied the history of those areas, and pondered, as everyone does who studies the Roman Empire, the causes of the fall of kingdoms. Marsh concluded that the Roman Empire fell apart because they misused the land – clearing forests, failing to maintain watersheds, losing their topsoil, their water, their crops. He thought back to his youth in Vermont, when just during his own lifetime, the state of Vermont had lost half of its forests to land-clearing farmers and settlers. And he decided to write a book about what humans have done, and are still doing, to their planet.

When Man and Nature was published in 1864, there was no conservation movement in American. There were plenty of people, like Henry David Thoreau, who wanted to curb America’s assault on the land and return to a simpler life, but they were more concerned with their own inner peace and the value of communing with the wilderness than with the fate of the planet. Almost no one was saying, hey, we humans are ruining the Earth by our activities. Marsh said just that. He pointed out the value of forests: the roots of the trees keep the soil in place, the humus from the leaves keeps the soil moist and allows water to accumulate in springs and aquifers. When we clear the land of trees, erosion sets in, we get floods in the spring and droughts in the fall, and the soil gets less and less fertile. He was not opposed to the logging of trees, but he thought we need to manage our lumbering ways, and plant trees as fast as we cut them down. And his principal evidence for the dangers of abusing the land was drawn from history, which was certainly novel. He walked the lands that ancient historians described as lush with fruit and olives and found only arid deserts devoid of people. Much of his book is just an extended history lesson in what happened to numerous empires that failed to protect the land from human abuse.

Even though you may never have heard of Man and Nature, it was a widely read book in the last half of the 19th century, and Marsh's advice began to be heeded. Our first National Parks were established soon after his book appeared, and the book was cited in support of the idea. A Division of Forestry was established within the Department of Agriculture, which became the U.S. Forest Service, and again, Man and Nature provided the justification. I know of no direct link between Marsh’s book and the first Arbor Day in 1872, but I would not be surprised if a connection was there.

I can’t say as I can recommend that Man and Nature go on your reading list. Our library has a first edition and I tackled it gamely, but the novelty that the 19th-century reader would have found in Marsh’s book was gone, and all that was left was a dry prose not much to my liking. But I do recommend a biography of sorts: George Perkins Marsh, Prophet of Conservation, by David Lowenthal (2000) that is, or at least was, available in paperback. Lowenthal’s writing is much more charming that Marsh’s, and he assesses the impact of Man and Nature with well-informed insight.

The house where Marsh grew up in Woodstock, Vermont, passed through several owners of significance and is now the centerpiece of the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, the only national park in Vermont (fourth image). The park is the subject of the image on the reverse of the Vermont state quarter.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.