Scientist of the Day - George Smith

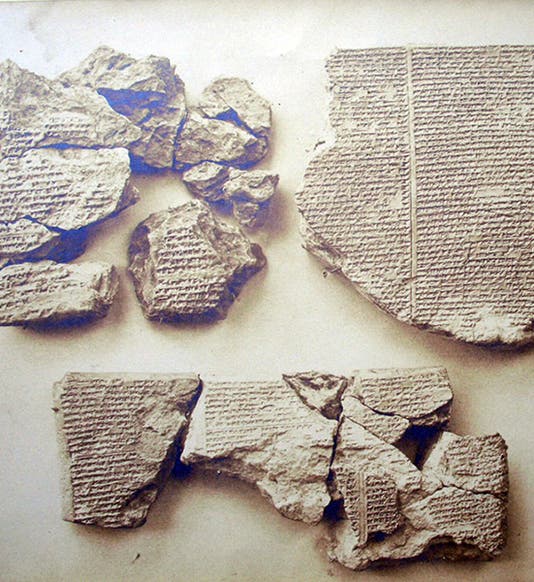

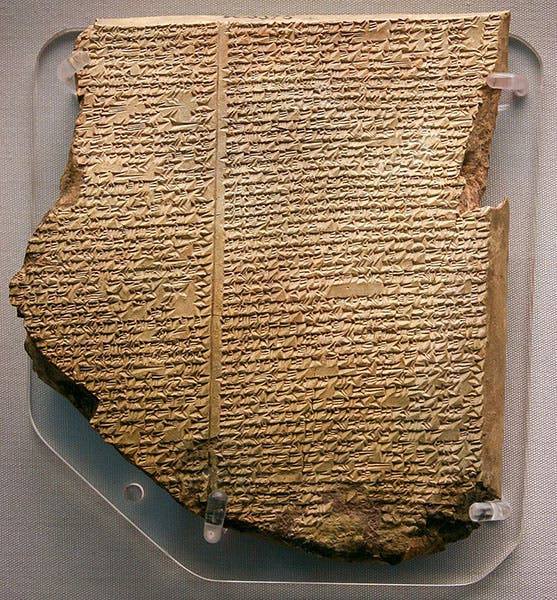

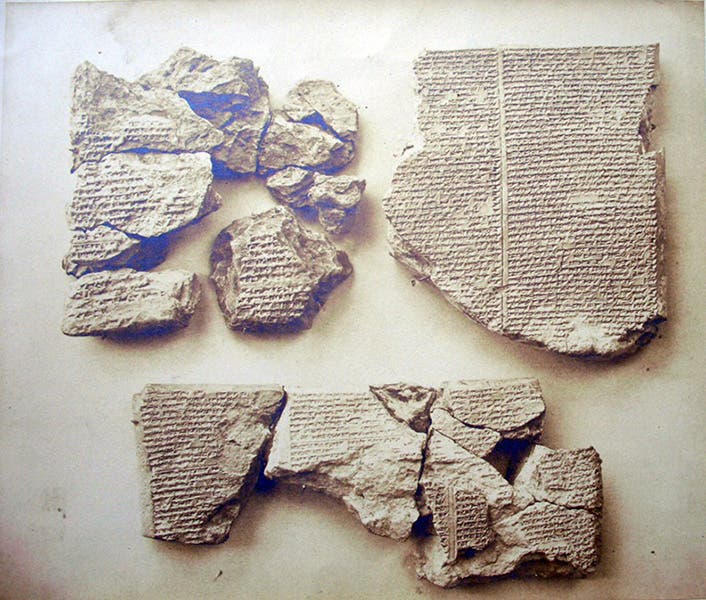

Fragments of the Epic of Gilgamesh identified and studied by George Smith, with a piece of the Flood Tablet, tablet 11, at upper right; photograph by Stephen Thompson, Chaldaean Account of the Deluge from Terra Cotta Tablets Found at Nineveh, and Now in the British Museum, 1872, Graphic Arts Collection, Princeton (www.princeton.edu)

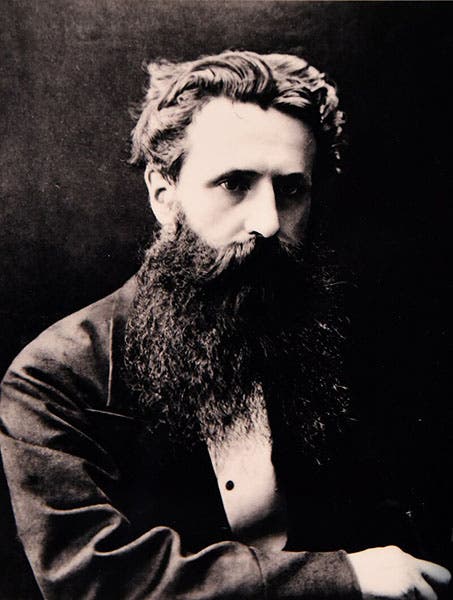

George Smith, an English Assyriologist, died Aug. 19, 1876, at the age of just 36. Smith had essentially no schooling and worked as a printer’s apprentice, but he taught himself to read cuneiform, the written script of ancient Mesopotamia, which was first deciphered when Smith was about 10 years old. He probably read the popular books by Austen Henry Layard about his discoveries at Nineveh, which is near Mosul. He happened to work very close to the British Museum, where Layard had sent all his spoils, so he spent his spare time there, reading cuneiform tablets, and he came to the attention of the Museum Assyriologists,especially Henry Rawlinson, who had first deciphered cuneiform in 1847, and who took young Smith under his wing. He gave Smith a job, sorting the 15,000 cuneiform clay tablets in the Museum that had been excavated from the Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, but which hardly anyone had even looked at.

One of Smith’s sorting categories was Mythology, where he put all the fragments that spoke of gods or heroes or creation myths. One day in 1872, he noticed, on a tablet labeled K-63, a reference to a ship landing on a mountain and sending out a dove. Struck by the parallels to the account of the Flood in Genesis, he searched for more tablets with further pieces of the story, and found them. Smith had discovered the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the earliest grand sagas in the written record. It comprised, when complete, 12 clay tablets, and on tablet 11, Gilgamesh related the story of his search for immortality, and of finding a human named Utnapishtim, the only immortal human, who, forewarned by the gods, survived a great flood, and saved his family, and all the animals, by building a large boat. The similarities to the account of Noah in Genesis were eerie, and soon, sensational.

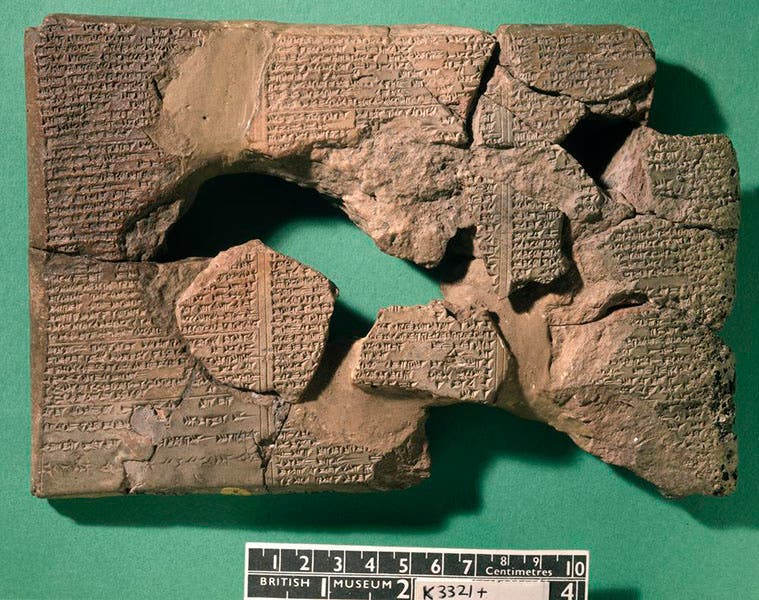

Smith read an account of his discovery, and a translation of the fragment of tablet 11, to the recently-founded Society of Biblical Archaeology in London on Dec. 3, 1872, and stunned everyone. A London newspaper offered to send him to Mosul to look for more fragments, all expenses paid, and he and the Museum accepted, so Smith got to be a real field archaeologist for a while, and he did find further fragments of the Gilgamesh epic. Smith began to publish popular works of his own, the big seller being The Chaldean Account of Genesis (1876), where Chaldean was a popular Victorian term for Babylonian. In his book, which we do not have in our collections, Smith included a wood engraving of a fragmented tablet from the Epic of Gilgamesh, fragments that he had assembled. The British Museum found all those fragments andrecreated the wood engraving in a photograph (third image), demonstrating the difficulties of being an Assyriologist, as Smith had intended with his original image.

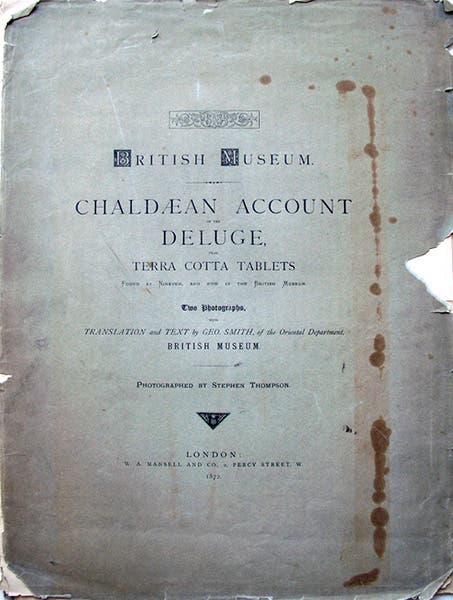

Not at all popular was a pamphlet issued in 1872 by the Museum that contained photographs of the fragments that Smith used in preparing his initial translation. There is apparently a copy of the pamphlet in the Graphic Arts Collection at Princeton, for in a blog post some years ago, they showed both the title page (fourth image) and one of the photographs (first image). The chunk at upper right is the famous fragment K-63, which the Museum calls the Flood Tablet and keeps on permanent display, renaming it object K-3375. If you look up Gilgamesh flood myth on Wikipedia, you will see a modern photo of K-3375; you can see the Museum’s description and photo here. We copy the Wikipedia photo below (fifth image)

Smith also found, among the crates of tablets in the British Museum, fragments of the other great Babylonian creation poem, the Enuma Elish, and he translated that as well. These two epics are the oldest surviving pieces of written literature, going back to at least 1800 BC. Unfortunately, before he could enjoy the success of The Chaldean Account of Genesis, Smith was sent back to Nineveh on another expedition in 1876, and this time, although he avoided the cholera plague that was sweeping the area, he succumbed to dysentery and died. Nevertheless, in his scant 36 years, he firmly laid the foundation for the study of the literature of ancient Mesopotamia

The tablets of the Gilgamesh Epic and the Enuma Elish that Smith identified and translated were actually discovered in Nineveh before 1854 by Hormuzd Rassam, an ethnic Assyrian who would make more important archaeological discoveries after Smith died. We will write a post on Rassam and the Rassam cylinder of Ashurbanipal in the near future.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.