Scientist of the Day - Gérard Paul Deshayes

Gérard Paul Deshayes, a French paleontologist, was born May 13, 1795. In the early 1820s, Deshayes began collecting fossil mollusks from the Paris basin. The rocks of the Paris basin were known to be Tertiary rocks, meaning they were more recent deposits than Secondary rocks, such as the chalky limestones across the Channel that make up the White Cliffs of Dover. It was generally thought then that all Tertiary fossils were pretty much the same age. The only sure way to know that one fossil is younger than another is to find it in a rock stratum that lies on top of a layer containing the other fossil, invoking Nicholas Steno’s principle of superposition. If you had two fossils from widely separate areas, you could not use superposition to determine relative age.

Deshayes discovered a new and ingenious way to infer the relative age of a fossil-bearing formation. He collected all the different species of mollusks he could find from that formation, and then compared them to the living mollusk species of that area. If none of the fossils were extinct, then the rock must be quite recent. If 50% of the fossils were represented by living species and 50% were extinct, then that rock was older than the first. And if all the fossils were from species now extinct, then the rock bearing them was older still.

Deshayes began publishing his Description des coquilles fossiles des environs de Paris in 1824 (he would publish the second and final volume in 1837), and by 1829, he had concluded that the Tertiary rocks of the Paris basin could be divided into three epochs or periods, based on the percentage of fossil species that are still living.

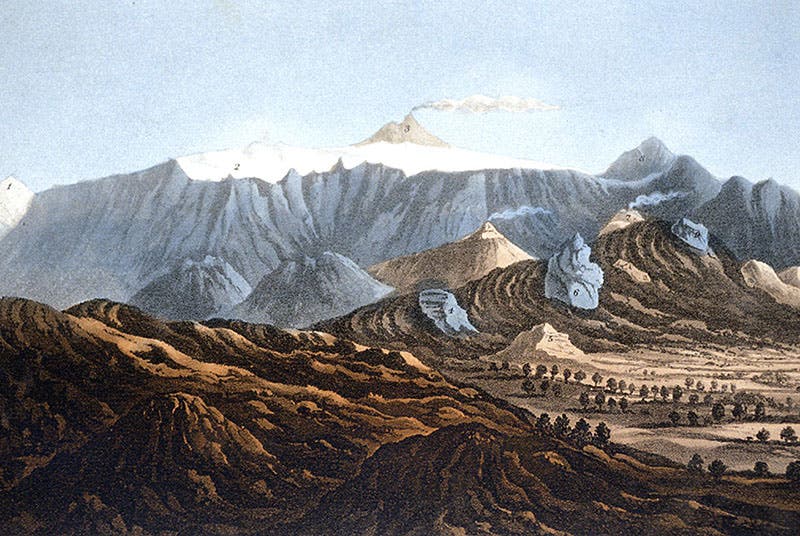

Now it just so happened that in 1829, a young British barrister morphing into a geologist came calling. Charles Lyell was returning from a visit to Mount Etna in Sicily and was wondering how to date the fossil-bearing rocks that he found beneath the huge mass of basalt and lava that comprised the volcano. Lyell met Deshayes in Paris and examined his large collection of living and Tertiary shells, and Deshayes showed him how to date Tertiary rocks by comparing the fossil species to living species in order to estimate the relative age. Lyell did so for his Mount Etna fossils and discovered that nearly all of them represented living species. So despite the fact that Mount Etna looks very old, it sits on top of a formation that is, geologically speaking, very young. It was Lyell's first realization that geological time is much different from human time, and of vastly greater extent.

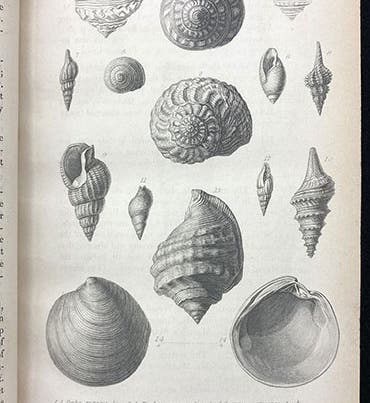

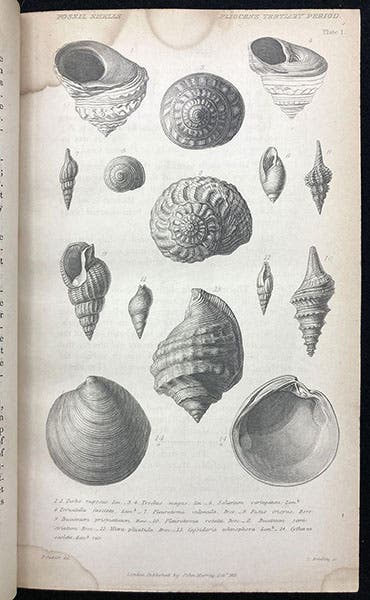

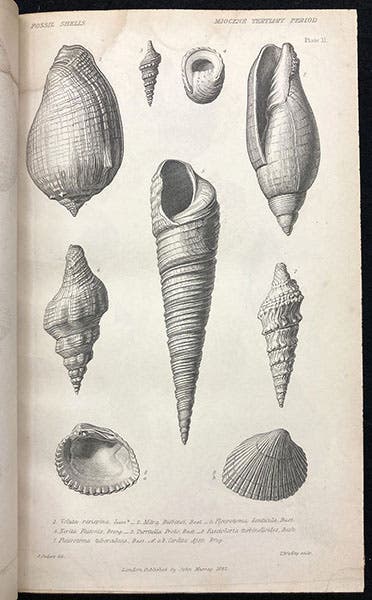

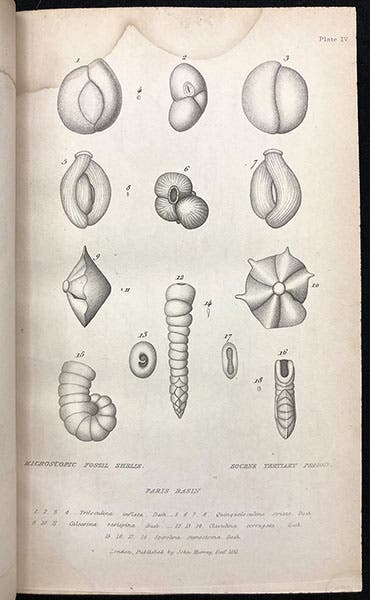

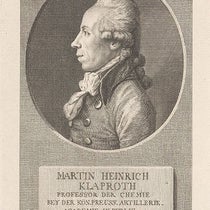

Lyell had already finished volume 1 of his Principles of Geology (to be published in 1830), but in volume 2 (1832), he used a drawing of Mount Etna as the frontispiece (third image, although he did not yet explain its significance with respect to geological time), and in volume 3 (1833), right at the outset, he announced that the Tertiary could be divided into 3 epochs, using Deshayes’ groupings, and giving Deshayes full credit. He even used Deshayes' own fossils, drawn by Paul Oudart, to support his tripartite division. Lyell's one original contribution was to give them names: Pliocene (more recent), Miocene (less recent), and Eocene (dawn of the recent). And even here, Lyell was not especially original, as the three names were suggested to him by William Whewell. We show here two of those plates, of Pliocene and Miocene shells (first and fourth images). We also could not resist showing a fourth plate, made from unpublished drawings by Deshayes of very tiny fossil shells as seen through the microscope. Some of the figures on this plate show the fossils natural size and will be mere dots to you at this scale (fifth image).

Lyell's three-volume Principles of Geology (1830-33) was one of the most influential geology books of the century – Charles Darwin took volume 1, the only one published so far, when he departed on HMS Beagle in 1831 – and a considerable chunk of Lyell's notion of geological time, and all of his division of the Tertiary, were indebted to Deshayes. Deshayes went on to finish his Description des coquilles fossiles, and produced a more extensive work on invertebrate fossils of the Paris basin in the 1850s. We do not have any of Deshayes books in our collections, a lacuna we will try to fill, if we can.

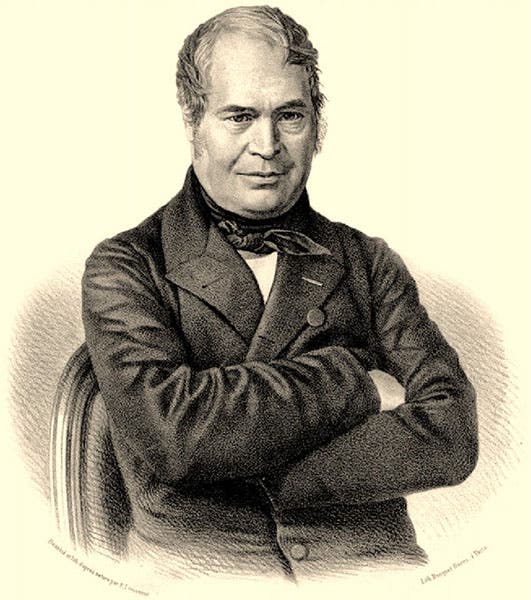

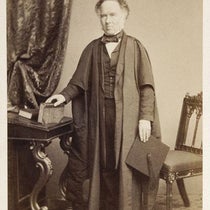

There is only one portrait of Deshayes that survives, a lithograph of an older version of Deshayes than the one Lyell met (second image). I think an original print is in the archives of the Museum of Natural History in Paris, but I could not find this original online, so I used one I found in a research paper on the academic website ResearchGate. There is also a bust somewhere. If anyone has access to good images of either bust or portrait and wishes to share, I would be happy to update the portrait here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.