Scientist of the Day - Gianfrancesco Sagredo

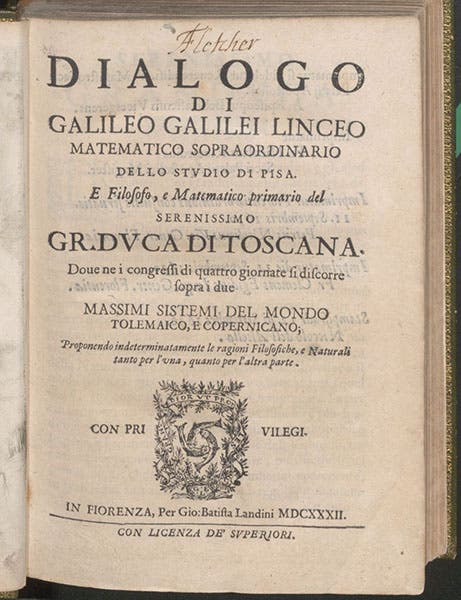

Giovanni Francesco Sagredo, a Venetian nobleman, diplomat, mathematician, and ardent foe of the Jesuits, died Mar. 5, 1620, at the age of 48 or 49. He spent some years as an envoy to Syria, where he accrued some of the luxury items, including a kilim rug, that you can see in his portrait of 1619 (first image).

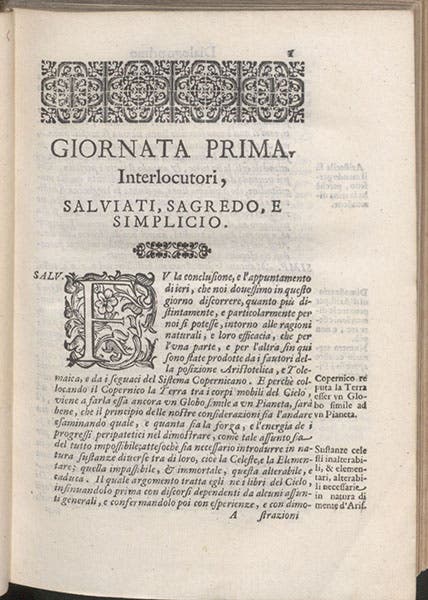

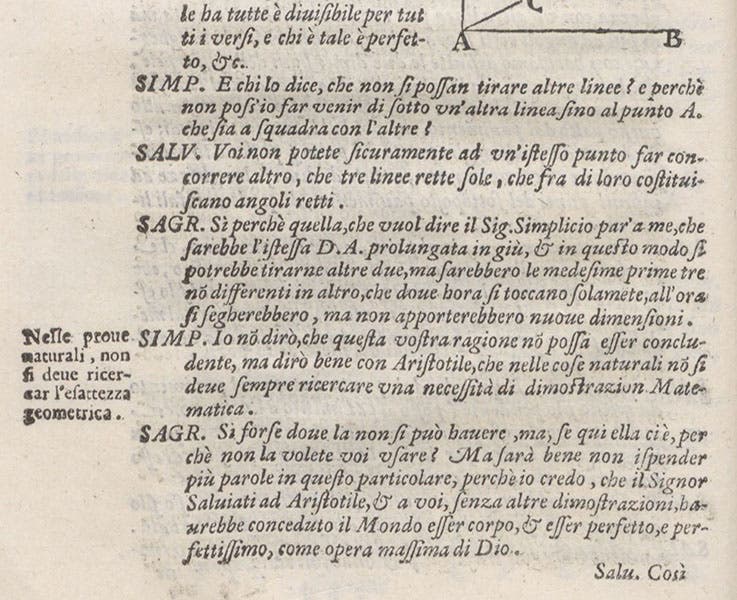

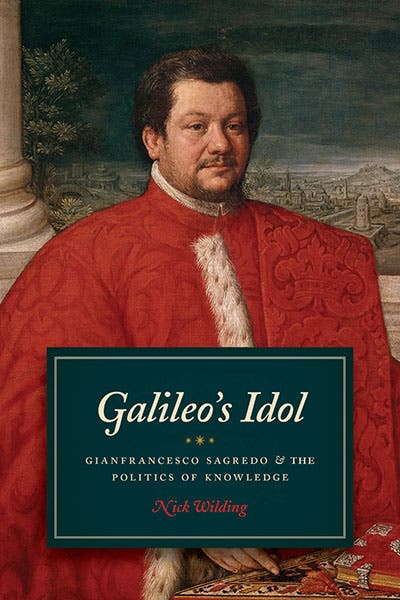

Sagredo is best known as a student, then colleague and friend, of Galileo Galilei. He studied with Galileo when Galileo was teaching in Padua (1592-1610); the two then became friends, and Galileo would stay at the Sagredo Palace when he visited Venice. At one point, Sagredo tried to use family strings to get Galileo a raise at Padua, an effort that failed, to Sagredo’s chagrin. Sagredo achieved a kind of immortality when Galileo made him a prominent character in his Dialogo (Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems, 1632). Sagredo is one of three "interlocutors" who got together on four successive days (in Sagredo’s palace in Venice) to discuss the system of the world, with their alternatives being the ancient geocentric system of Ptolemy and Aristotle, or the more recent heliocentric system introduced by Nicholas Copernicus in 1543. The Sagredo of the Dialogo is a bright fellow, initially uncommitted, who listens to the arguments of Salviati (a Copernican, named after another of Galileo’s deceased friends) and Simplicio, a firm (and not too bright) Aristotelian, named after, well, you figure it out. Sagredo’s role in the book is to bait Simplicio, repeatedly telling him, for example, that giving something a name is not quite the same as explaining what it is. Salviati is too nice to call Simplicio a fool; Sagrego does not really do so either, but he has no problem goading Simplicio into demonstrating it time and again. We include some images from our best copy of the Dialogo, showing the title page; the first page, where the interlocutors are introduced; and a sample page, where the speakers are identified in the margin (second, third, and fourth images).

Sagredo was appointed Venetian consul to Syria in 1607, and he departed for Aleppo. When he returned in 1611, Galileo had left Padua for Florence, rewarded by the Medici family for his Sidereus Nuncius (1610), and the two would never meet again. But they corresponded, and over 100 letters from Sagredo to Galileo survive (Galileo's letters to Sagredo are lost), and it is from these letters that we know as much about Sagredo as we do (which still, is not a lot). We know that, in addition to being one of Galileo's greatest advocates and defenders, Sagredo was partial to the work of William Gilbert, whose book De magnete was published in London in 1600 and eagerly devoured by members of the Padua circle like Sagredo, Galileo, and Paolo Sarpi. Sagredo’s interest in magnetic studies (undertaken in the hope of solving the longitude problem) became known to Gilbert, who described Sagredo as a "great Magneticall man" in a letter before he died (in 1603). Tycho Brahe also praised Sagredo in a letter.

Sagredo commissioned a portrait in 1619, from the Bassano brothers, Leandro and Gerolamo, of Venice. The initial sketch was by Leandro, but he was so busy that Sagredo grew impatient and had it finished by Gerolamo. When it was completed, he shipped it off to Galileo in Florence, as part of an exchange of portraits (first image). The portrait of Sagredo hung in Galileo's living quarters, and it is said that he wrote both the Dialogo and the later Discorso (Discourse on the Two New Sciences, 1638) under the watchful eyes of Sagredo. The portrait eventually disappeared, but it turned up in the 1930s in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, where it was eventually identified as being that of Sagredo. A prominent role in the attribution was played by Nick Wilding, whose book, Galileo's Idol: Gianfrancesco Sagredo and the Politics of Knowledge (2014) is now our standard source on Sagredo matters, and who was a Fellow at our Library several years ago, studying our collection of Galileiana. Galileo, in a letter of 1636, referred to Sagredo as his idol, hence the title.

Dr. Wilding discovered another portrait of Sagredo, also by Gerolamo Bassano, that was painted at least 7 years earlier than the Ashmolean portrait, and which is now in the Zhytomyr Regional Museum in Ukraine. I was unable to locate it online, but you can find it in his book, as plate 1. The Ashmolean portrait of Sagredo is reproduced on the dust jacket of Galileo’s Idol (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.