Scientist of the Day - Gustav Kirchhoff

Gustav Robert Kirchhoff, a German physicist, died Oct. 17, 1887, at the age of 63. Kirchhoff graduated from Albertus University in Königsberg in 1847, moved to Berlin for several years, and then took a position in 1850 at the University of Breslau in Silesia (now the University of Wrocław, Poland). Four years later, he accepted an offer from the University of Heidelberg, and he would spend most of his career there, until he moved back to Berlin in 1875.

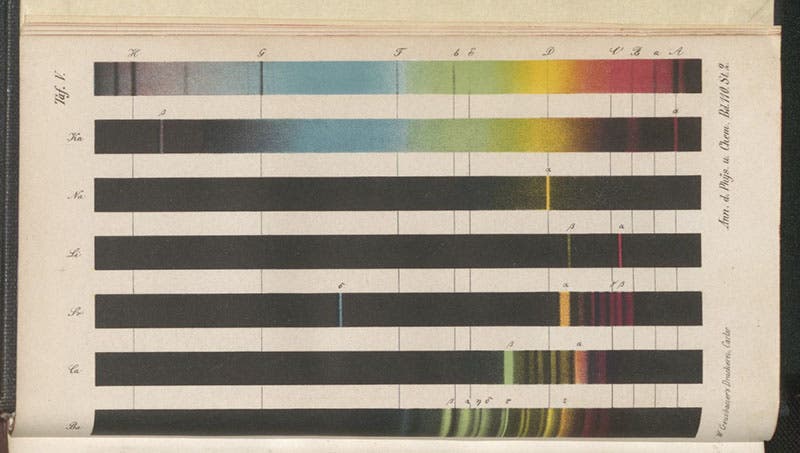

Kirchhoff made significant contributions to many fields, including electromagnetism and thermodynamics. But he is best known for his work in spectroscopy. Indeed, he founded the discipline, with the help of his colleague from across the aisle, the chemist Robert Bunsen. In 1859, they began investigating the spectra produced when they vaporized various elements, such as lithium and calcium. They did so by heating minute samples of an element, vaporizing it with a Bunsen burner, letting the light pass through a slit into a prism, which broke the light down into its constituent colors, and then viewing the resultant spectrum with an eyepiece. They discovered that while dense gases emit continuous spectra, such as you see in a rainbow, a rarefied gas, such as you get by burning sodium, emits a series of bright lines of different colors, and the spectrum is far from continuous. Hydrogen, for example, emits light at 4 different wavelengths, each line of a different color, while sodium emits only two bright yellow lines, very close together. Every element, in fact, has a different bright-line spectrum, and that spectrum is characteristic of that element. That means you can identify an element by the spectrum it emits when burned, which is a big improvement on traditional wet-lab chemical analysis, such as what you went through when you tried to identify your unknown in high-school chem lab. The instrument invented by Kirchhoff and Bunsen (lens, slit, prism, eyepiece, all in a closed tube), came to be called a spectroscope, and the science of spectrum analysis was named spectroscopy. You can see a drawing of the spectroscope they used, and Bunsen’s burner, at our post on Bunsen, where you may also see several photographs of Kirchhoff and Bunsen together.

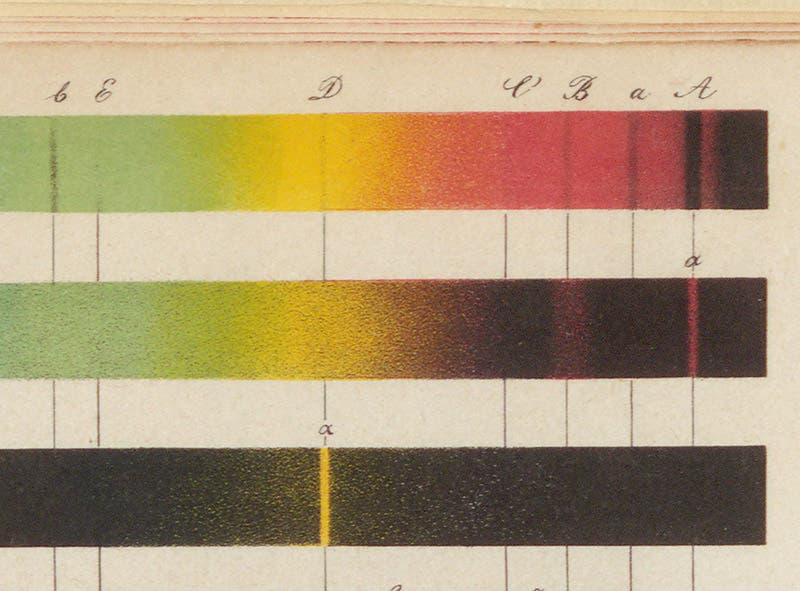

Kirchhoff, who was the physicist of the two, knew that the spectrum of the Sun contains hundreds of dark lines (discovered by Joseph Fraunhofer in 1814) that had not been explained by astronomers. He and Bunsen proposed that each dark line in the solar spectrum was an absorption line that corresponded to a bright-line emission line from some element. The Fraunhofer lines were therefore collectively the chemical signature of the elements that make up the solar atmosphere. In the paper they published in 1860, announcing the results of their spectroscopic examination of the elements, they included a simplified dark-line solar spectrum on the same plate where they presented the emission lines of elements such as potassium and sodium (second image), and they drew a line connecting the double-yellow line of sodium to the dark double line (called the D line) in the solar spectrum, suggesting that the D line is caused by the presence of sodium in the solar atmosphere (see detail, third image).

Spectroscopy is one of the most significant, and most unexpected, of the new sciences that came out of the mid-19th-century. Spectroscopy would allow scientists to determine not only the chemical make-up of the Sun, but soon thereafter, the physical constitution of the stars, which many people had thought would forever lie beyond the pale of human inquiry.

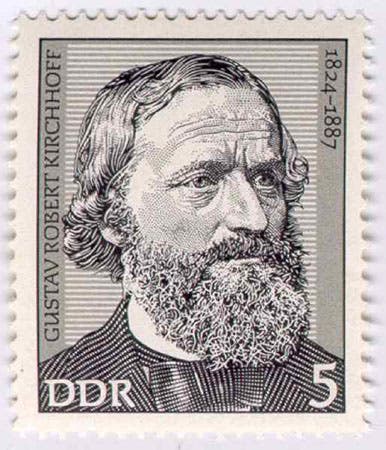

Another great invention of the mid-19th-century was photography, and Kirchhoff was part of the first generation whose lives were tracked by portrait photographers. We have many excellent portraits of Kirchhoff, and we show three of them here: the young investigator (first image), the middle-age mature scientist (fourth image), and the elder statesman of science (fifth image). It is nice to have an abundance of portraits to choose from. A fourth portrait was used as the basis of a postage stamp issued in 1974 by the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), on the occasion of the sesquicentennial of Kirchhoff’s birth (sixth image).

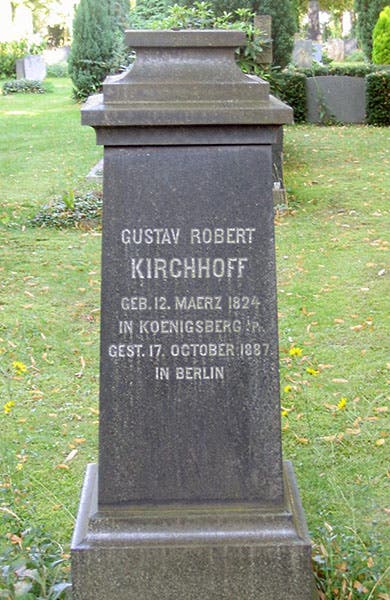

Kirchhoff died in Berlin in 1887 and was buried there, in Old St. Matthew’s Churchyard in Berlin-Schöneberg (seventh image). He shares the cold, cold ground with Rudoph Virchow, a renowned cell biologist whom we have yet to profile, and the brother’s Grimm, who will probably never pass muster as Scientists of the Day.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.