Scientist of the Day - Gustave Eiffel

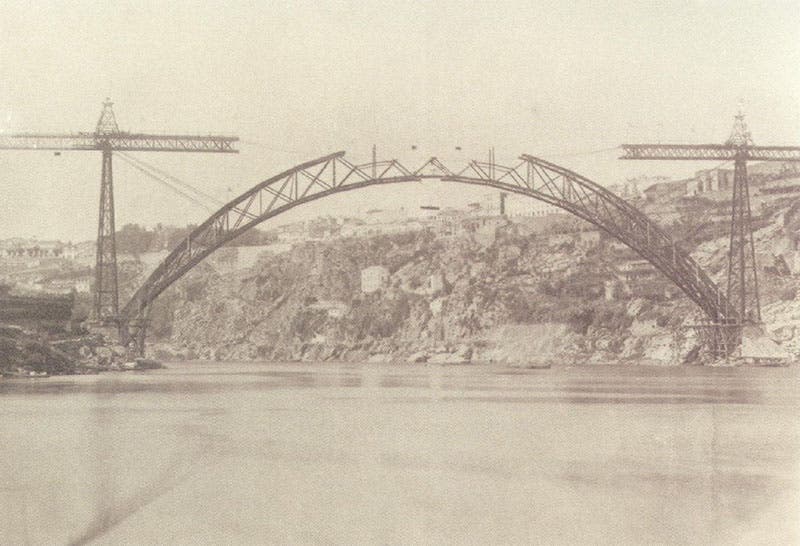

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, a French civil engineer, was born Dec. 15, 1832. He attended the Central School for Arts and Manufactures, one of the two best engineering schools in France, and then worked for a variety of firms before setting up his own company in Paris in 1875. Many of his early works were train stations and bridges. I like bridges better, so I'll show you the Maria Pia bridge over the River Douro near Porto, Portugal, which is a single crescent-arch bridge built of wrought iron (first and second images). When it was completed, it just edged out the Eads Bridge in Saint Louis as having the longest central span in the world (525 feet vs. 520 feet).

The Eiffel Company's other well-known bridge is the Garabit Viaduct, which spans the Truyère River and its valley in central France (third image). It too was built of wrought iron and has a single arch with a span of 541 feet, again the longest in the world for a brief while. Both bridges were single-track railway bridges and are no longer in use for railway traffic.

By 1881, Eiffel had enough of a reputation that when Auguste Bartholdi was looking for an engineer to design the interior structure for his copper-clad Statue of Liberty, he chose Eiffel. Eiffel provided a four-column pylon that supported the statue nicely, and still does.

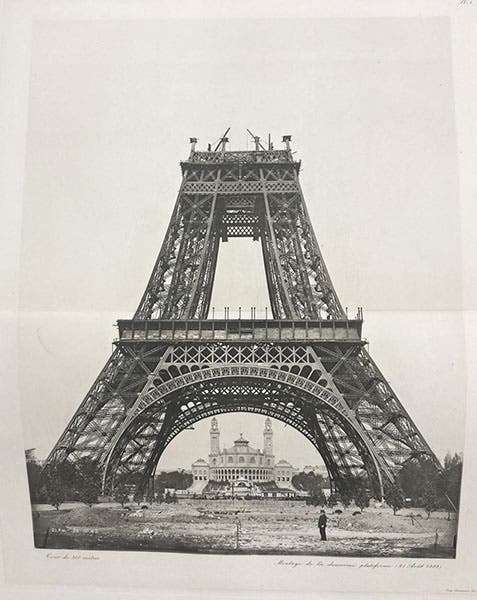

Eiffel is of course best known for his 300-meter tower built for the Universal Exposition of Paris in 1889, and which opened to the public on today’s date, May 6, 1889. We talked a little about the Eiffel Tower in a post on Eiffel that appeared in 2014, when this series was just getting started, and like most of those early posts, it was brief, too brief, which is why we are adding to it today.

Eiffel's tower was an amazing piece of speed engineering. Designed and constructed in just over 2 years, it consisted of 18,000+ pieces of puddled iron, each piece fashioned at Eiffel's factory and then shipped to the site on the Champ de Mars and hot-rivetted into place. There were 2.5 million rivets used, with each rivet requiring 4 men working together to install. I would not like to have been the construction engineer on that project, although Eiffel seemingly had it all worked out, since as far as I can tell, there were no major snafu's during the construction process, and it was finished right on schedule.

The greatest obstacle to completion might have come from opposition raised by the arts community. Many famous Parisians protested the tower, decrying the monstrosity that was being foisted on them and the Paris skyline. Eiffel seemed unfazed by the clamor and never lost his equanimity, and argued that engineered structures had their own beauty, which was just as worthy of admiration as other forms of art. The opposition, vociferous though it was, failed to stop construction of the tower.

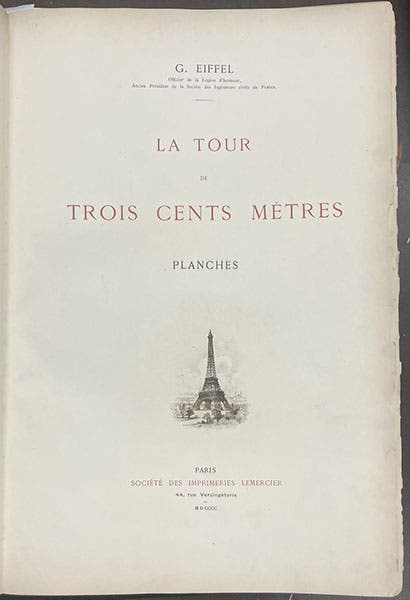

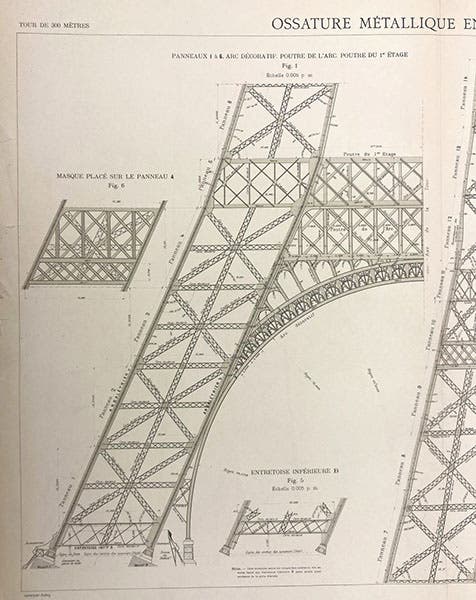

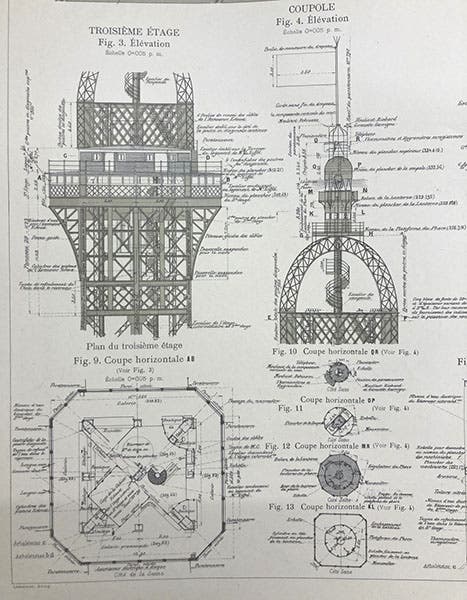

In our first post on Eiffel, we showed three photos of the construction process, taken from a book Eiffel published in 1900 that we have in our collection, La tour de trois cents mètres (1900). The occasion was the Universal Exposition of 1900, for which Eiffel had the tower refurbished, adding four restaurants on the first level and elevators that ran up three of the legs. The book consists of a pair of large folio volumes, one for text and one for plates. Our copy is not in great shape, like many books published around 1900, with now-brittle pages, but the images in the atlas are beautiful and amazingly detailed, with the close-up drawings showing every rivet hole. We show an assortment of those here, to go with the three photos in our first post.

The original contract gave Eiffel a share of the income admission for 20 years, at which time the tower was to be taken down. Eiffel shrewdly began installing physical laboratories, meteorological stations, and radio equipment in the tower, making the tower indispensable for Parisian science and commercial communications, and, as everyone knows, it was not dismantled in 1909, but is still there, now the most famous and most visited of all Parisian landmarks. All it needs to keep it going is a fresh coat of rust-proof paint every seven years, which has been faithfully applied on schedule except for wartime interruptions.

As most regular readers of this series know, the first level of the Eiffel Tower has an exterior frieze with the impressed last names of 72 French scientists. This was envisioned by Eiffel himself, and there is a drawing in his book of one side of the frieze with its 18 names (see our first post). We have shown close-ups of the frieze many times, whenever we profile someone whose name is on the tower (such as Hippolyte Fizeau or Joseph Lagrange). But Eiffel did not compile the list, and the men who did (we can be sure they were men) did not include a single woman on their list, which has long provoked outrage, as it should. Recently, social media came alive with news that the names of women scientists were going to be added. I hope this is true. But I cannot find any official confirmation of this news. We shall have to wait and see. Meanwhile, see my post on Sophie Germain for my take on the names on the tower. I also wrote a clerihew on Germain and the tower, illustrated by Melissa Dehner, that appeared in Scientific American in 2021.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.