Scientist of the Day - Hans Krebs

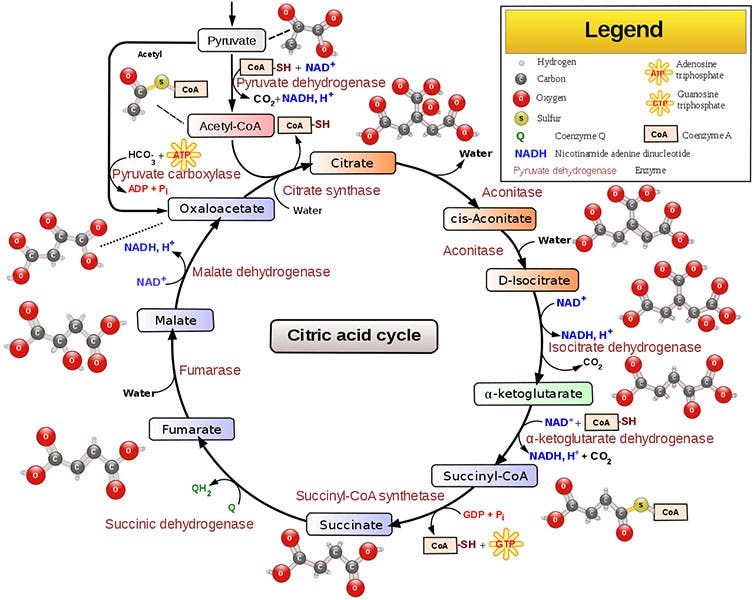

Hans Adolf Krebs, a German biochemist, was born Aug. 25, 1900. In 1953, Krebs received a share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine, for discovering the citric acid cycle, also called the Krebs cycle,. The citric acid cycle is an essential metabolic pathway in all living things, whereby organisms convert sugars, fats, and protein into energy-storing compounds. I could not explain the Krebs cycle to you if I were threatened with water-boarding, but I can show you a diagram that will eloquently indicate why an easy explanation from anyone is highly unlikely (second image). So instead of discussing the Krebs cycle, we will talk instead about the unusual circumstances that gave Krebs the chance to pursue his important research.

Krebs was a German Jew, with a position at the University of Freiberg in the 1930s. When Adolf Hitler issued the "Law for Restoration of the Civil Service" on Apr. 7, 1933, Krebs and every other Jew occupying a government or university post in Germany was suddenly out of a job. A far-sighted British economist, William Beveridge, Director of the London School of Economics, was in Europe when Hitler's decree was issued, and he returned home convinced that something needed to be done for the displaced German academics. He set up the Academic Assistance Council in April 1933, convincing important British intellectuals to sign on – men such as Ernest Rutherford, J.B.S. Haldane, and William Bragg – and they immediately sought to find places in English universities and institutions for some of the disenfranchised German professors. Krebs was offered a position at Cambridge in 1933, from which he moved after several years to the University of Sheffield, and it was there, in 1937, that he discovered his eponymous cycle. Others helped by the Council include Ernst Boris Chain, who emigrated to Cambridge, then Oxford, where he won the Nobel Prize in 1945 for helping develop penicillin, and Max Born, a physicist who was invited to Cambridge in 1933 and thence to Edinburgh, where he won the Nobel Prize in 1954 for his work in quantum mechanics. Men of letters were aided as well; Ernst Gombrich, who would become the dean of 20th-century art historians, NIkolaus Pevser, the eminent architectural historian, and Karl Popper, an influential philosopher of science, all got new starts in England through the help of the Council. The Academic Assistance Council was at once one of the most benevolent and one of the most beneficial investments made by England during the 1930s.

After 20 years in Sheffield, Krebs accepted a professorship at Oxford and spent the last 13 years of his academic career there, and even after his retirement in 1967, he continued to work and publish right up to his death in 1981. His house in Iffley, Oxford, has a blue plaque over the front door. We show you the charming house (fourth image); you can see the blue plaque here.

In 2015, Krebs’ Nobel prize medal was sold at auction (for $350,000) to fund a trust fund to aid students and chemists who have had to flee their home countries. That seems to us like the best of all possible uses for a Nobel prize medal.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.