Scientist of the Day - Hans Sloane and the British Museum

The British Museum, the world's first truly public national museum, opened its doors on Jan. 15, 1759. The founding of the museum was the direct result of a bequest by Hans Sloane, who had died Jan. 11, 1753, and left his collections of 71,000 items, including 50,000 books, to the English nation. We discussed Sloane's early life, including a voyage to and stay in Jamaica, 1687-89, and the publication of his Natural History of Jamaica, in our last post. Today we will look at the last half of his career, the founding of the Museum, and recent controversies concerning Sloane, as the Museum attempts to deal with its colonial past.

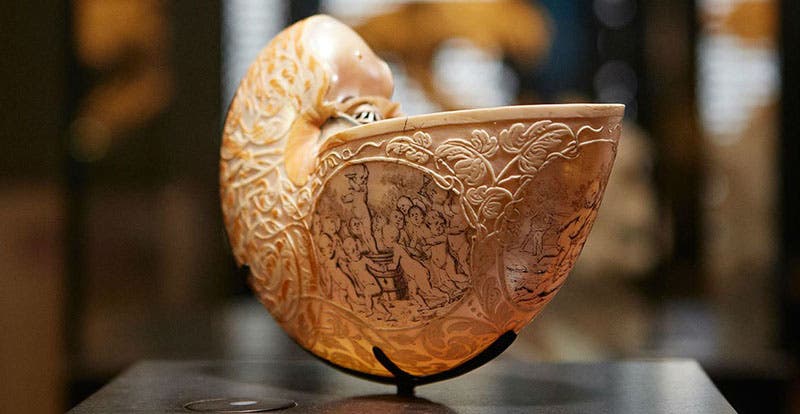

Upon his return from Jamaica, Sloane became secretary of the Royal Society, and continued in that post untl 1713. He also acquired a wife in 1695, the wealthy widow of a plantation owner in Jamaica, which provided him funds to enlarge his collections, which he did by acquiring the complete collections of others. He started with the collection of William Courten, a longtime friend whose collection passed to Sloane on his death in 1701. Sloane also acquired the collections of James Petiver when he died in 1718. He bought some 91 original watercolors of plants and insects from Maria Merian, which she had used to publish her Metamorphosis (1705). Numerous other collections came his way, especially when he moved to a large house in Chelsea (much of the land from which would pass to the Chelsea Physick Garden).

Sloane was philanthropic by nature and supported numerous causes and struggling societies with £100 gifts right and left. His physician’s practice prospered, and he became Physician in Ordinary to Queen Anne, King George I, and George II. His status in the Royal Society was up and down; naturalists praised his collections, but physical scientists such as Isaac Newton looked down upon him, as they looked down on all non-mathematical scientists. Sloane seems to have been forced from his job as secretary by enemies, but he had the last word, as he was elected President of the Royal Society in 1727, upon the death of Newton. He was at the same time president of the Royal College of Physicians, a rare dual honor.

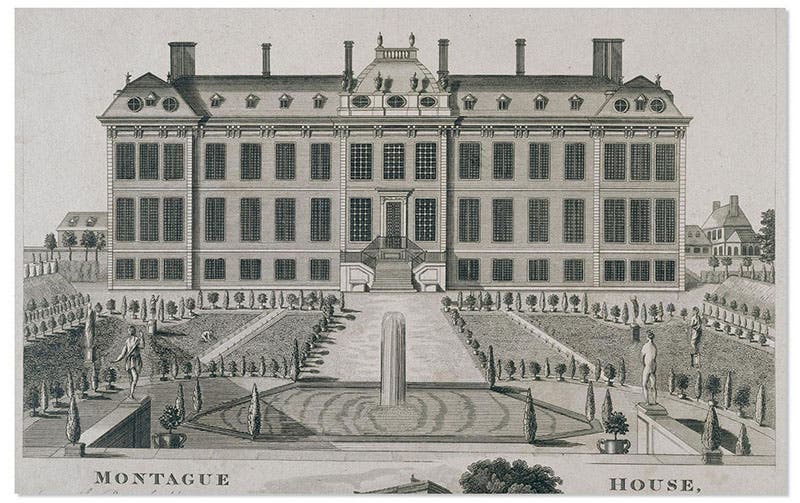

Sloane lived a long life, and well before his death in 1753, he began thinking about the disposal of his collections. No existing museum or repository seemed suitable, so he decided to leave everything to the English nation, provided that the government would pay £20,000 to his estate, to support his two surviving daughters, and would found a new museum to house his things, one that would be open free to the public. Parliament agreed to the stipulations with an act of 1753, founding the British Museum. It took some time to find a suitable building, but they settled on Montagu House in Bloomsbury (fourth image), and by 1759, the Museum had been staffed and collections moved in and arranged for viewing.

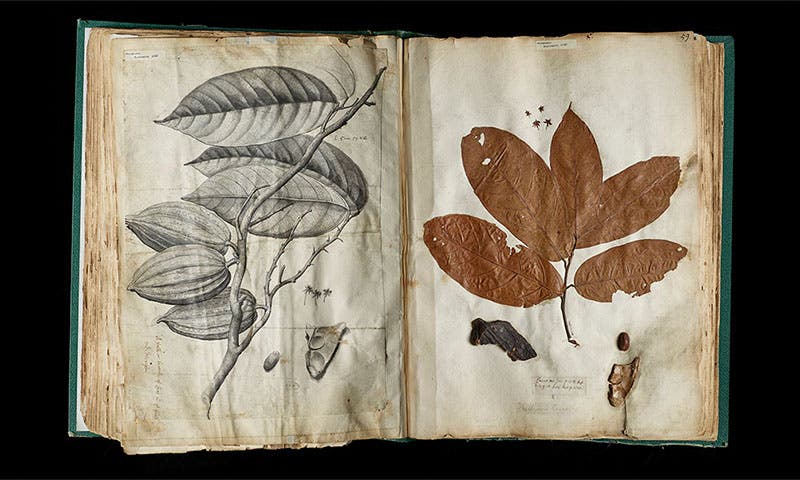

The number of "things" Sloane donated to the nation is usually put at 71,000, but this is misleading, since his herbarium, or collection of dried plants, was arranged in 265 volumes, which counts as 265 items, but they contain over 120,000 individual plants, which if counted separately, would certainly swell the numbers (second image)..

One feature of Sloane’s incessant collecting that is often under-appreciated is that he was an excellent and meticulous cataloguer. His catalogues of his herbarium, and of his “vegetable substances” (hundreds of small boxes holding walnuts, cocoa seeds and the like) are detailed and legible and still survive in what is now the Natural History Museum. Sloane did not – could not – do all this himself, but hired cataloguers and taxonomists, whom he supervised closely. As a result, we know where nearly all of his specimens came from and when they were collected.

Petiver had also acquired specimens from others (all collectors of the time seem to have cross-collected like this), and some of the butterflies in his collection were bought from or given by Eleanor Glanville, England’s first lepidopterist. Sloane acquired them from Petiver, and you may encounter them in the Natural History Museum today, thanks to Petiver and then Sloane. You may see one of those mounts in our post on Glanville, written by a former Library Fellow, Michele Pflug.

Sloane was in the news just over three years ago, when the British Museum began trying to come to terms with the fact that much of its collection was acquired via colonialism, which was in turn based on slavery, at least in Sloane’s time. Sloane’s wife inherited plantations in Jamaica that were slave-based, and the income from those plantations subsidized much of Sloane’s collecting. Sloane, as the founder of the British Museum, had always had a place of honor in the Museum, in the form of a terracotta bust by Michael Rysbrack, fashioned in 1736 (first image). In August of 2020, the museum administration had the bust removed from its pedestal and moved to a closed case that documented the connections between colonialism, slavery, and the business of collecting. The move was both praised and criticized, and is certain to be further discussed. So far as I know, there has been no suggestion that any of Sloane’s collections should be removed from the museum.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.