Scientist of the Day - Henrik Grønvold

Henrik Grønvold, a Danish illustrator and naturalist working in England, was born Sep. 6, 1858. He moved to London in 1892, intending to move on to the United States, but he never left England, except for one short expedition to the Salvage Islands. He worked originally for the British Museum (Natural History), both as an artist and a taxidermist. After 1895, he freelanced, and he was such a good illustrator, and lithographic artist, that he never had any problem making a living.

At first, Grønvold drew wildlife of all kinds, but he soon narrowed his field of operations to bird illustration. His colored lithographs appeared frequently in the ornithological journal Ibis, which had been founded in 1859 by Philip Lutley Sclater. Since as far as I know, there is no list of lithographs that Grønvold did for Ibis, I pulled a volume from the shelves more or less at random – I chose 1910 – and I had no trouble finding Grønvold images – it seemed like every picture of a bird in that volume was by Grønvold. I include three of them here, our first three images. These are hand-colored, which surprised me, because most bird illustrations were being printed in color (with a great loss in richness) by this time.

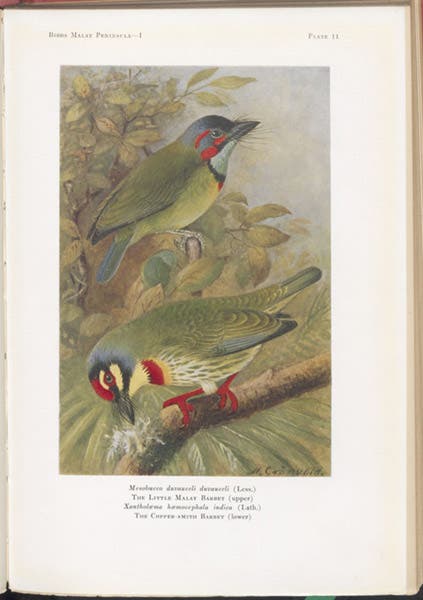

Our lead image is especially engaging, showing two small finches that live on mats of vegetation growing in swamps in southern Africa. I had never heard of Paludipasser locustella, so I looked it up on Wikipedia, and was surprised (and not surprised) to see that Grønvold 's illustration was used to illustrate the article. Our second image was drawn by Grønvold to illustrate an article in Ibis by William Robinson on the birds of Malaysia (more on Robinson in a moment), and the third to illustrate yet another article by a third author.

With so much evidence of his talent appearing in journals such as Ibis, it is not surprising that Grønvold was soon engaged to illustrate entire books. Books on the birds of particular regions, or books on specific families of birds, had started coming out in the 1870s, illustrated by the likes of Johan Keulemans, and by 1920, they were being published in torrents, books such as George Shelley's Birds of Africa (1896-1912), Henry Eliot Howard's British Warblers (1907-14), and Herbert Robinson's Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1927- ), all of which, not coincidentally, were illustrated by Grønvold.

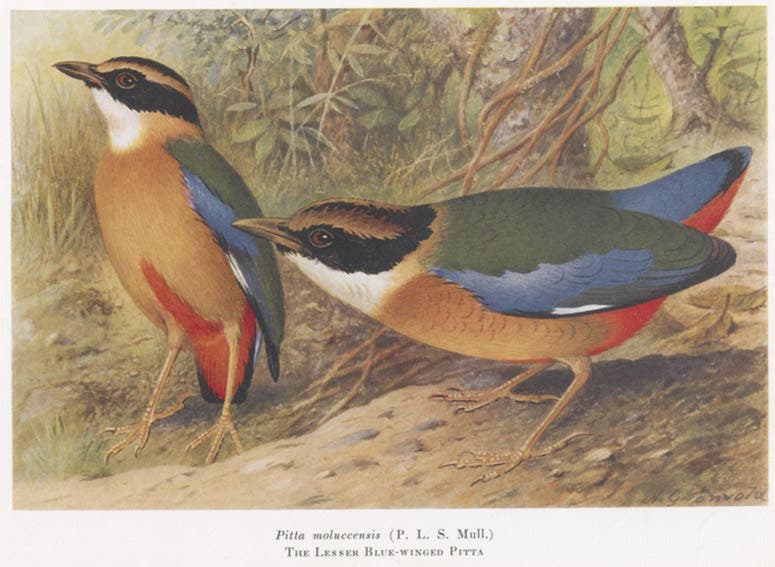

Our collections are not especially strong in regional bird books, but we do have Robinson's Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1927- ), so I retrieved the first volume and selected some of Grønvold 's illustrations to provide our next three images. You will note that these are not as vivid as the plates in Ibis, because the paintings were reproduced by some sort of photo-mechanical process, which provided a much flatter image. But if you can look past that, you will see that they are skillfully drawn, even though Grønvold was never within 5000 miles of Malaysia. This is a four-volume work, and just one of many Grønvold was working on in the 1920s, so he was a busy man, producing thousands of bird illustrations over the course of his career.

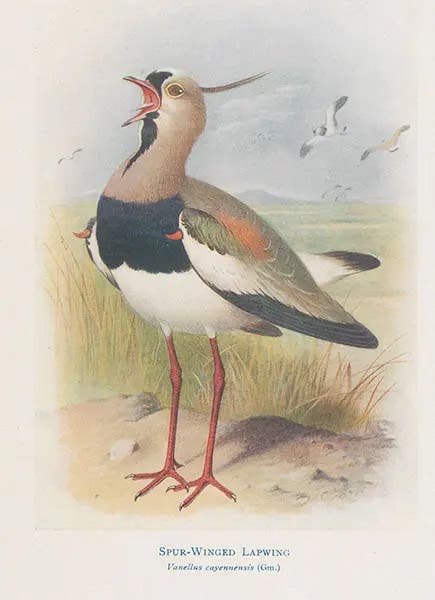

Some of my favorite Grønvold bird paintings were done for William Henry Hudson's The Birds of La Plata (1920). These are appealing because the birds (rather like Hudson) are so lively. We show one of those here, the saucy Spur-wing lapwing (seventh image), to entice you to read our post on Hudson, where you will find three more Grønvold paintings. And by the way, our artist signed his name his entire life as “Grönvold”; why we now have to write “Grønvold,” I could not say.

But I can say that I get very sad when confronted with the facts of life as experienced by gifted illustrators such as Grønvold. He seems to have received little appreciation from any of the authors whose books he illustrated. Herman Robinson, author of the Birds of the Malay Peninsula, did not mention Grønvold on the title page, in the introduction, in the acknowledgments, or even in the table of contents of the plates, all of which were drawn by Grønvold. The only place his name appeared is where Grønvold signed his paintings, and that didn’t even transfer to the captions. It is hard for us to imagine how taken for granted illustrators were in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, lumped into the same anonymous class as typesetters, press operators, and binders, and rarely publicly congratulated on their talent and dedication. We do not even have a portrait of Grønvold. He deserved much better treatment from his contemporaries, and he deserves better from us.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.