Scientist of the Day - Henry Dana Washburn

General Henry Dana Washburn, a U.S. Army officer and Civil War veteran, was born Mar. 28, 1832. After a distinguished war career, he was appointed Surveyor-General of Montana Territory in 1869. In August of 1870, he led an expedition to explore the area around Yellowstone Lake. Washburn was accompanied by Nathaniel Langford, a writer-adventurer, and by a small army contingent led by G.C. Doane. Near the end of August, they climbed a mountain some 10,000 feet in height, and the group agreed to name it Mt. Washburn. It still has that name.

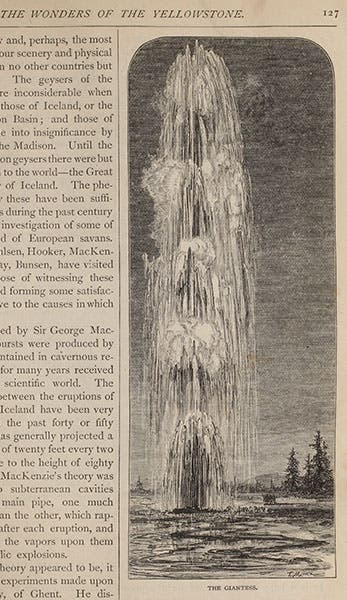

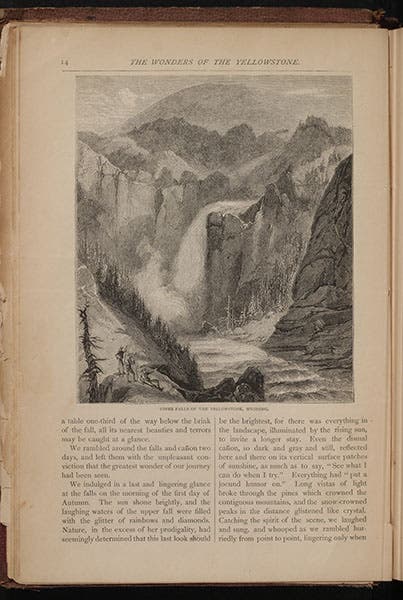

The highlight of the exploration came on Sep. 18, 1870, when the party rode into the Upper Yellowstone Basin and sighted a geyser in full eruption, spouting water and steam to a height of over 100 feet. When it repeated these eruptions on a regular basis, they decided to call it "Old Faithful." As they explored further, they found other geysers, some even more impressive than Old Faithful, and they gave them names like the Beehive, the Castle, the Grotto, the Giant, and for the largest, the Giantess. As they explored, they also beheld the glory of the Upper and Lower Falls of the Yellowstone River.

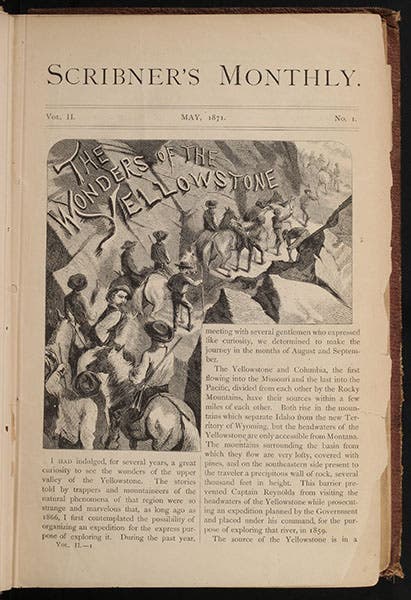

The Washburn party entering Yellowstone basin, first page of article by Nathaniel Langford, Scribners’ Monthly, May 1871 (author’s collection)

The Giantess geyser, wood-engraving after Thomas Moran, Scribners’ Monthly, June 1871 (author’s collection)

When they returned from the expedition, Langford wrote a two-part article for Scribners' Monthly, which appeared in the May and June issues, 1871. The article was richly illustrated with wood engravings, some of them after designs by a young and unknown artist, Thomas Moran, who would later go on to achieve great fame as an artist of the West. We wrote a post on Langford in 2020, and showed several of those illustrations, but at the time we were deep in the pandemic and restricted to just two images per post. So today we show some of the other text engravings from the Scribners' Monthly article, including the Grotto geyser (first image), the first page of the first part of the article, with its playful headpiece depicting the Washburn party (third image); the Giantess geyser erupting (fourth image); a detail of a bird's-eye-view map of Geyser Basin (you can see the full view in our post on Langford), and a large wood-engraving of the Upper Yellowstone Falls, that Thomas Moran would later memorialize in a monumental painting. In our post on Moran, you can see not only his painting, but a two-page opening from part two of the Scribners' Monthly article, which included the wood-engraving of the Giantess in context.

Bird’s Eye View of the Geyser Basin, detail of wood-engraving, Scribners’ Monthly, June 1871 (author’s collection)

Upper Falls of the Yellowstone River, wood-engraving, Scribners’ Monthly, May 1871 (author’s collection)

Washburn and his party did not discover Yellowstone; there are multiple claimants for that. But the Washburn expedition led directly to the Hayden expedition of the next year, which in turn inspired the designation by Congress of Yellowstone as the country’s first national park. You can pursue this chain of events a little further in our posts on Moran and Ferdinand Hayden.

Henry Washburn never saw any of this happen. He returned to his Indiana home after his successful expedition and died just four months later, on Jan. 26, 1871, of causes unknown to me. He was only 38 years old. He is buried in Riverside Cemetery in Clinton, Indiana. You can see his tombstone here.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.