Scientist of the Day - Henry Foster

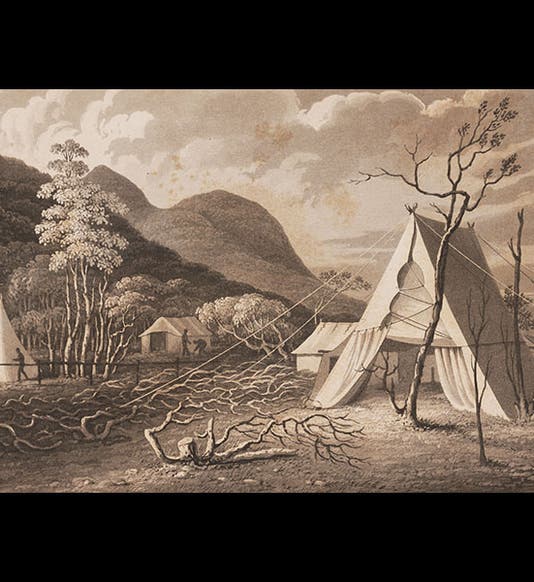

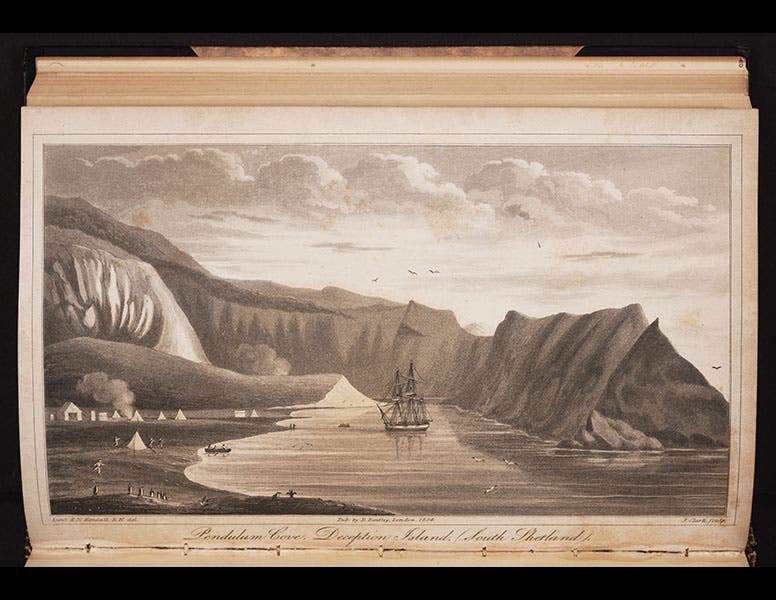

An engraving depicting one of Foster’s pendulum experiments, as it was set up on Staten Island.

Henry Foster, a British scientist and naval officer, died Feb. 5, 1831; his date of birth is unknown. Foster participated in several expeditions to the Arctic between 1823 and 1827. On the first of these, he assisted the Army officer and physicist Edward Sabine as he used a pendulum to try to establish the exact force of gravity at various locations in the Greenland Sea. On the second voyage, 1824, Foster accompanied Edward Parry in an attempt to navigate through the Arctic archipelago. The quest was unsuccessful, but Foster's magnetic and pendulum studies so impressed the Royal Society that he was awarded the Copley medal, the Society's highest annual award. In 1827, Foster sailed with Parry again in a fruitless attempt to take a ship to the North Pole. The narratives of both of the Parry voyages, his 3rd and 4th overall, were featured in our 2009 exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance, although we didn't mention Foster in our descriptions.

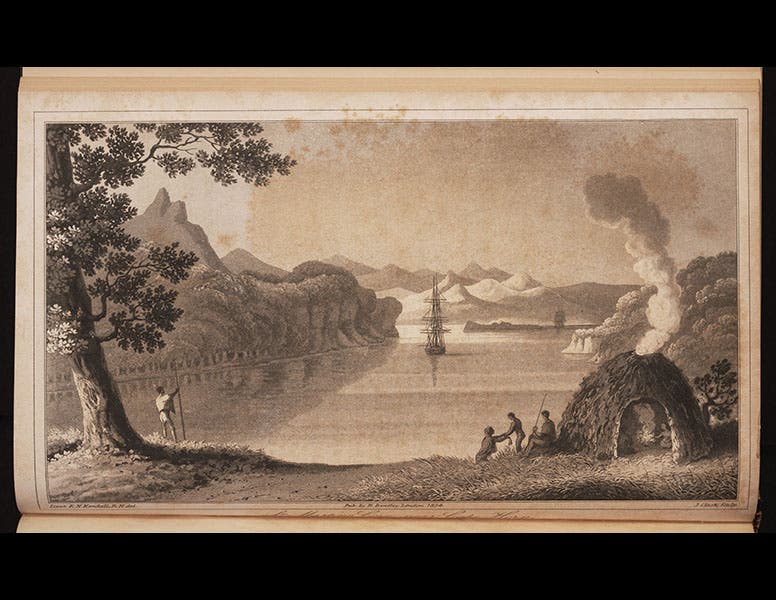

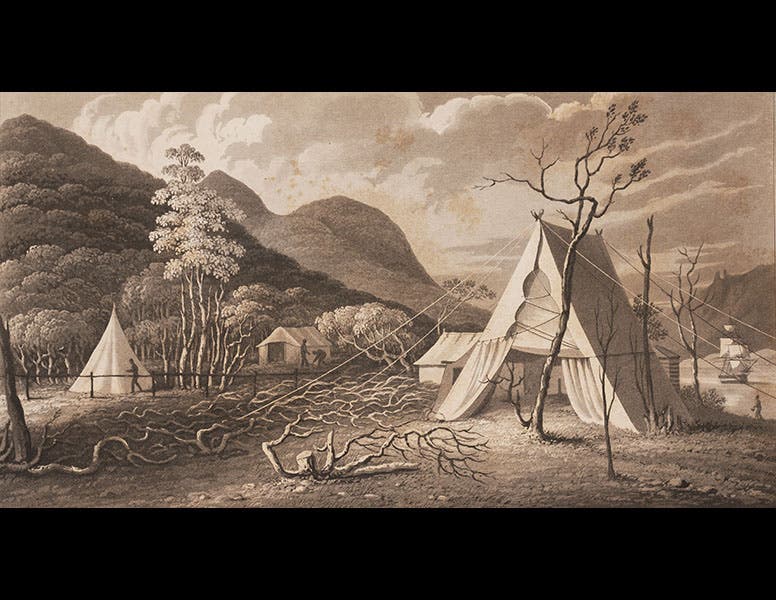

In 1827, Foster got his own command, as he was handed the tiller to HMS Chanticleer and sent on an exploring voyage to the South Atlantic. His mission was to survey the various islands east and south of South America, to make magnetic and pendulum studies wherever possible, and (it was hoped) to discover some new territory for Great Britain. He made it all the way down to the South Shetland Islands, and he discovered some new islands near Cape Horn, which he named the Wollaston Islands, after the English chemist William Wollaston. The narrative of the voyage of the Chanticleer (1834) has an engraving depicting one of Foster’s pendulum experiments, as it was set up on Staten Island (first image). Chanticleer also explored the islands of Tierra del Fuego and the natives who lived there, and there is a depiction of one of the Fuegian huts in the narrative as well (third image).

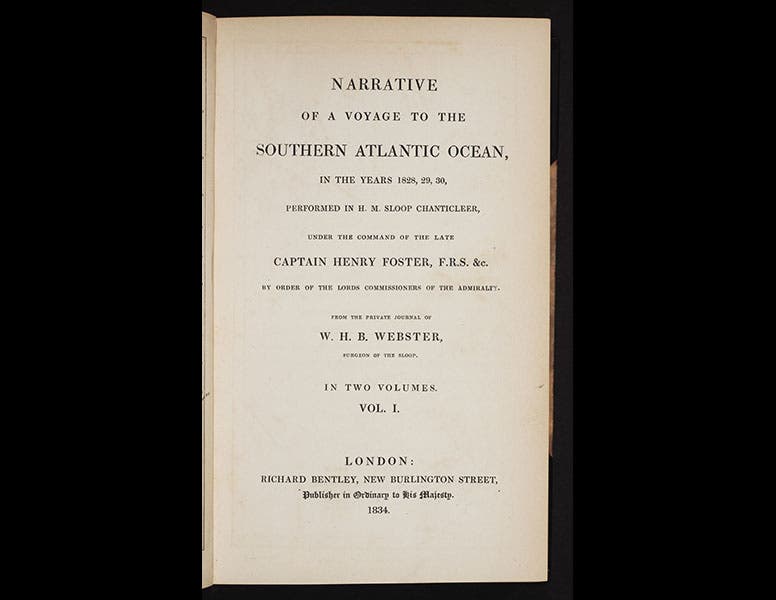

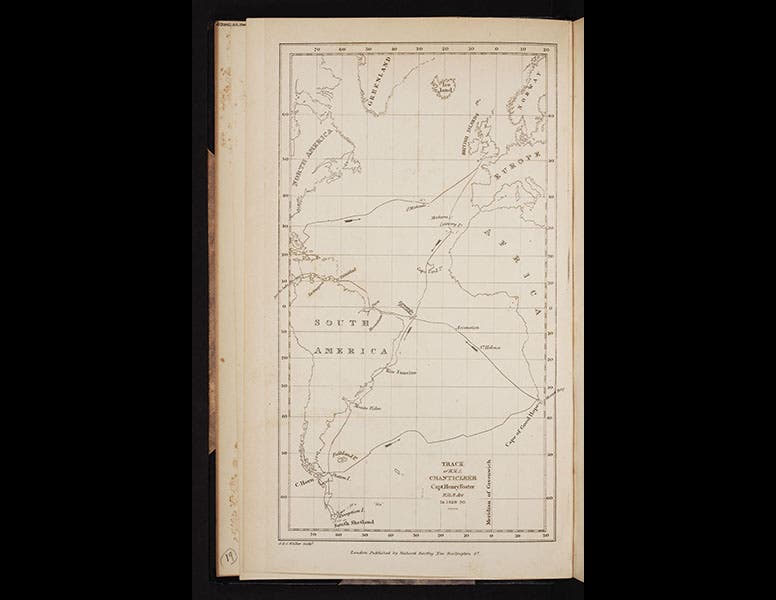

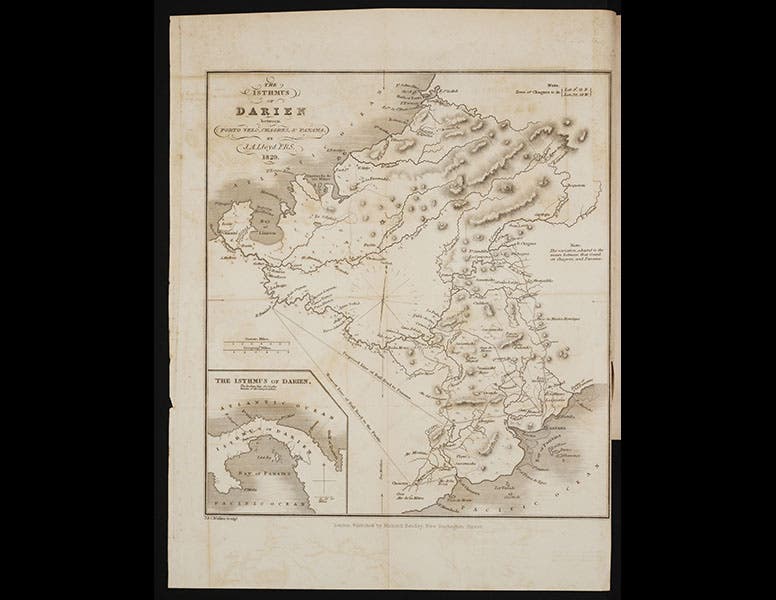

With the surveying completed in the South Atlantic, headed for the Isthmus of Panama (by way of Africa!), to do further geodetic work there. The narrative includes a map of the entire voyage as a frontispiece to volume 1 (fourth image), and a map of Panama in the second (sixth image). Foster would certainly have wished that the Panamanian section of his mission had been scrubbed, for while he was navigating down the Chagres River, on this day in 1831, he toppled out of a large canoe while trying to walk from stern to bow, and drowned. He was 34 years old. The narrative of the voyage, usually written by the captain, had to be compiled by the ship's surgeon, William Webster (second image). We have this two-volume set in the History of Science Collection. The map of Panama in the second volume was used in our 2014 exhibition celebrating the centennial of the Panama Canal.

Foster's Chanticleer had one last odd historical role to play. The Admiralty intended to send Chanticleer back to South America for another set of surveys in 1831, but the ship was so beaten up by its travels that they grounded it and sent another, younger ship in its stead. That ship was HMS Beagle. Charles Darwin’s life history might have been quite different, had the Chanticleer been a little more sea-worthy.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.