Scientist of the Day - Henry Schoolcraft

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, an American explorer, Indian agent, and would-be ethnologist, was born Mar. 28, 1793, in New York. Schoolcraft was a member of the Lewis Cass expedition that explored Lake Superior and the land to the west (the upper Mississippi basin) in 1820. In 1822, he was appointed as an Indian Agent, responsible for Indian Affairs in northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Schoolcraft was not a typical agent; his wife, Jane, was the daughter of an Ojibwe woman, and Henry learned and spoke Ojibwe. He was not immune to the prejudices of American settlers and frontiersmen against native Americans, but he seems to have admired Indian culture and to have recorded information and stories from them for his entire life.

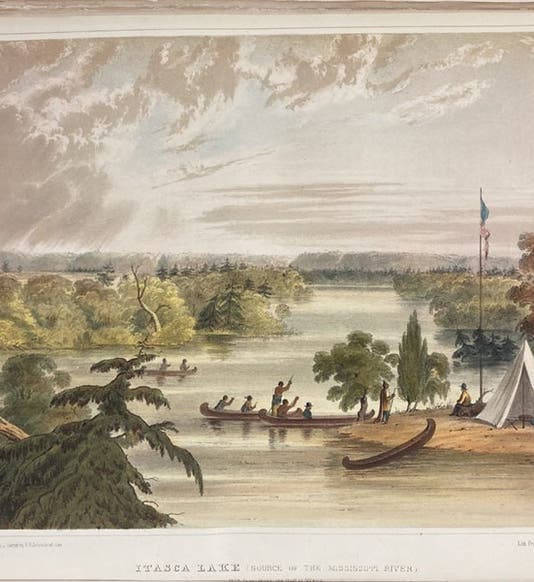

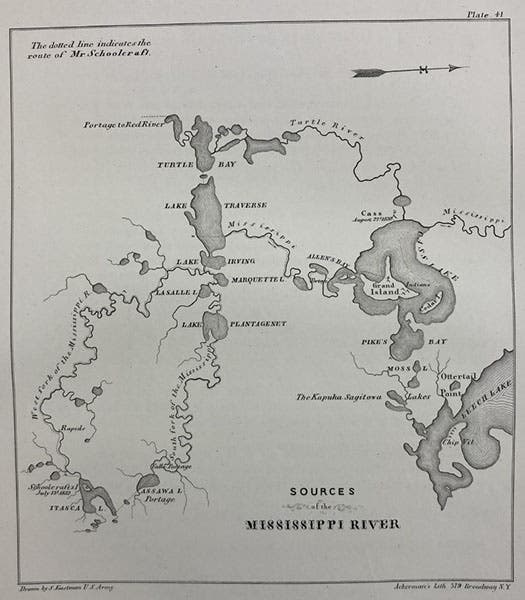

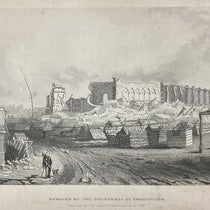

Schoolcraft had sought the origin of the Mississippi River while part of the Cass expedition, but the season had been late and the water level low and they couldn’t get to the source. He returned to northwestern Minnesota in 1832 and succeeded, with the help of an Ojibwe guide, in tracing the river to a lake that he named Lake Itasca. It is curious that the lake then had a French name, Le Biche, which would seem to suggest that some French explorer had been there before him, but perhaps the earlier voyageur had not traced the Mississippi connection. Common wisdom has it that Schoolcraft came up with the name "Itasca" by shortening the Latin phrase "Veritas caput"-- "the true head." But since this explanation was first offered by a third party in 1872, 8 years after Schoolcraft's death, and since Schoolcraft is unlikely to have known his "caput" from his "cauda", Latin-wise, I have my doubts about this attribution. Schoolcraft published a Narrative of his expedition in 1834, with a map, but this was not one of the treatises we acquired from the Engineering Societies Libraries, although many other works just like it were included. However, Schoolcraft did publish a map of the upper Mississippi, and a view of Lake Itasca, in a later publication (discussed below), and we show those here (first and third images).

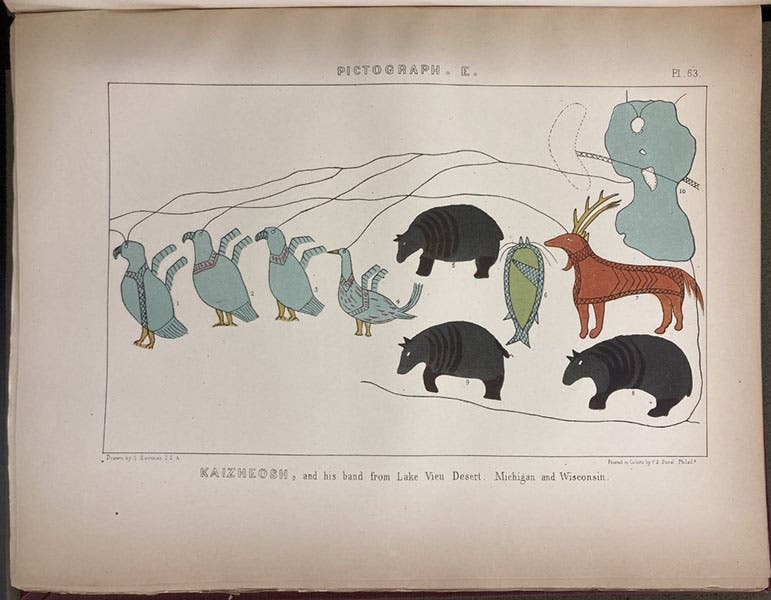

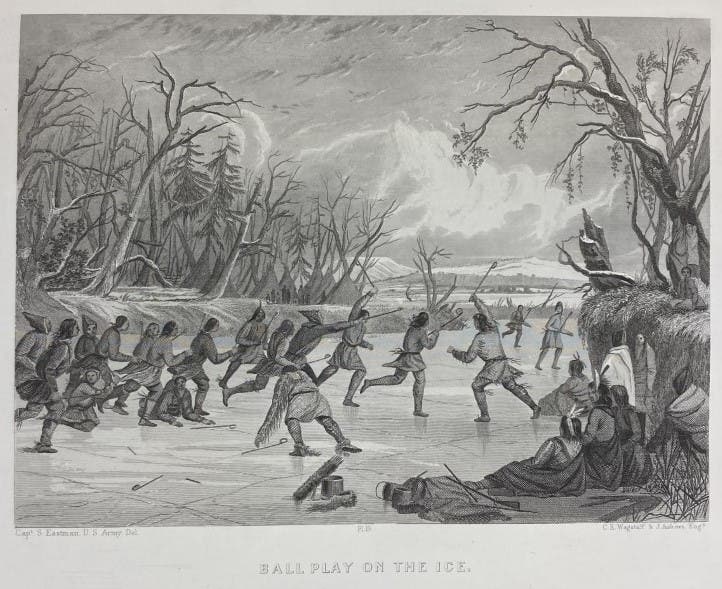

Schoolcraft was promoted to Superintendent for Indian Affairs for the Northern Department in 1839. However, when William Henry Harrison was elected President in 1841, Henry lost his post, and he and Jane returned to New York, where he continued his ethnological work on native American culture (and Jane unfortunately died). In 1846, Henry was commissioned by Congress to write an encyclopedia on native American culture. This he succeeded in completing; it was published in 6 very thick quarto volumes from 1851 to 1857, with the title: Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. We have the complete set of Schoolcraft's magnum opus in our library, and it is a remarkable work, both for the text and for the illustrations. Since publication was paid for by Congress, as with the Pacific Railroad Reports, the expense of engravings and lithographs was not a problem, and there are hundreds of plates in the six volumes, many colored. Schoolcraft wanted George Catlin to illustrate it, but Catlin turned down the invitation, and Schoolcraft settled for Seth Eastman, who was an Army officer and explorer and a very accomplished draughtsman, as you can see; he certainly deserves to be better known. Since we only have room for six of his illustrations, we will have to write a post on Eastman at some point, so we can include 6 more.

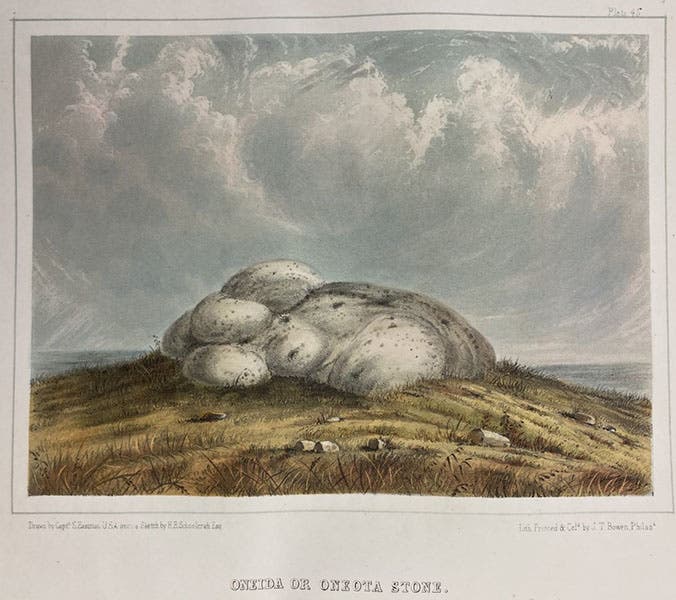

To make matters manageable, I chose plates from just volumes 1 and 2, and tried to convey the variety of images in the original work I.ended up with: a view of an encampment of Winnebago wigwams (fourth image), the Oneida stone in upstate New (fifth image), various pictographs observed in Michigan and Wisconsin (sixth image), and a view of some Dakotas playing ice hockey (seventh image). The map of Lake Itasca and the view of native canoes on Lake Itasca (with what may well be Schoolcraft himself in front of his staff tent at the right, third image), were also from the first volume of the work. It was very difficult to stop at six images; I really look forward to learning more about Eastman so I can write a second post.

Schoolcraft died on Dec. 10, 1864, at the age of 71; I do not believe his death was war-related. Henry and his second wife Mary are buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.