Scientist of the Day - Henry Weekes

Henry Weekes, an English sculptor, was born Jan. 14, 1807. Weekes was primarily a portrait sculptor, one of the most successful of his era (the early Victorian period), fashioning busts and statues for the likes of Queen Victoria and the Duke of Wellington, and memorials for such historic figures as Raphael, but he also sculpted portraits of a surprising number of scientists. His best-known marble scientist is probably the Francis Bacon which sits outside the Trinity College Chapel at Cambridge, but as it is not even close to being my favorite, I have put it further down the page (sixth image). Weekes sculpted a number of busts of geologists, which is odd, because they were not all for the same patrons; the busts portrayed such figures as Roderick Murchison, Adam Sedgwick, and William Buckland, the last of which we show for our lead image. It was commissioned for the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and completed in 1858.

Weekes also did portraits of a variety of medical figures. There are two of these that are especially nice. The first is a full-body sculpture of John Hunter, which he completed in 1864 for the Royal College of Surgeons, where it still stands, or sits (third image). It was clearly inspired by the portrait of Hunter painted by Joshua Reynolds in 1786, a copy of which you can see as the fourth image in our post on Hunter.

The other medical figure sculpted by Weekes, and my favorite of all of his scientific portraits, is a standing statue of William Harvey, which he created, like the Buckland bust, for the Oxford Museum. The neo-Gothic Museum was built between 1854 and 1860, with a large inner court, around which were placed 28 statues of scientists, all newly commissioned. Various sculptors were involved, with the greatest number of commissions going to Alexander Munro. Weeks was only assigned one statue, but it is one of the finest in the Museum. It portrays William Harvey, discoverer of the circulation of the blood. The Illustrated London News singled it out for an illustration in 1863 (fourth image), and we also show a modern-day photograph from a different angle (fifth image). Notice that Harvey is holding, as his attribute, a human heart, which seems a reasonable enough choice. On the ArtUK website, you can see a detail of the stony heart, as well as a detail of Weekes’ signature on the base of the statue.

Weekes’ most dramatic, and most controversial, sculpture did not portray a scientist, but we thought we would mention it anyway, since one of its subjects, Mary Shelley, was once a Scientist of the Day. The marble sculpture is an ode in stone to Percy Byssche Shelley, and it shows him, washed in from the sea where he drowned, and cradled by Mary, very much in the mode of Michelangelo’s Pieta. It was commissioned by the Shelleys’ son, and was intended for Mary’s grave in St. Peter’s Church in Bournemouth. Apparently the authorities there were appalled by the starkly realistic portrayal of the dead Shelley and rejected the commission. So Weekes’ masterpiece now sits inside Christchurch Priory, also in Dorset. You can see a semi-distant view on ArtUK, and a more-detailed close-up at this Flickr page.

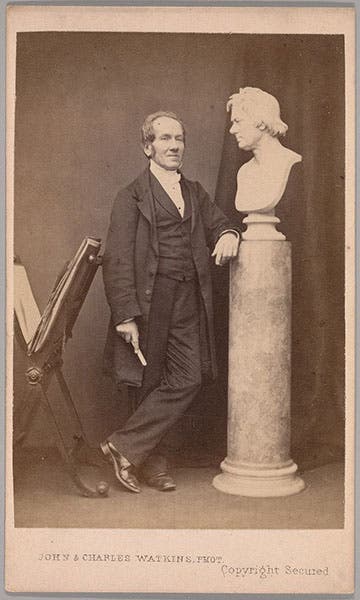

The portrait of Weekes that we show as our second image is a carte de visite from the 1860s, in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I have not figured out which of his busts he is contemplating. It does not appear to be one of his scientists.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.