Scientist of the Day - Hermann Schaaffhausen

Hermann Schaaffhausen, a German anatomist, died Jan. 26, 1893, at the age of 76. Schaaffhausen, a professor of anatomy in Bonn, was the professional authority consulted by Johann Carl Fuhlrott after he came to possess an assortment of human-like bones unearthed in 1856 in the Feldhofer quarry in the Neander Valley (Neanderthal) just east of Düsseldorf. The limestone quarrymen uncovered the partial skeleton of what they thought was a bear and called in Fuhlrott, who taught at a Gymnasium in Elberfeld. Fuhlrott recognized the bones as those of a human, but not a typical human. The skull cap was thick and long, with a shallow forehead, and the bone ridges over the eye sockets were quite pronounced. Both femurs were present and they were thick and heavy, and more curved than usual. Fuhlrott also noticed that the bones were almost completely fossilized, suggesting that they had been there for a long time. Perplexed, Fuhlrott took the bones to the University of Bonn, where he encountered Schaaffhausen. Schaaffhausen knew human anatomy quite well – that was his profession – and he concluded that these were indeed human remains, but not those of any modern human. It was not only a primitive form of human, but probably prehistoric. If so, it might be evidence of human antiquity. In 1856, except for the skull discovered in the Engis cave in Belgium in 1830, there was no other fossil evidence to suggest that humans were any older than 6000 years or so.

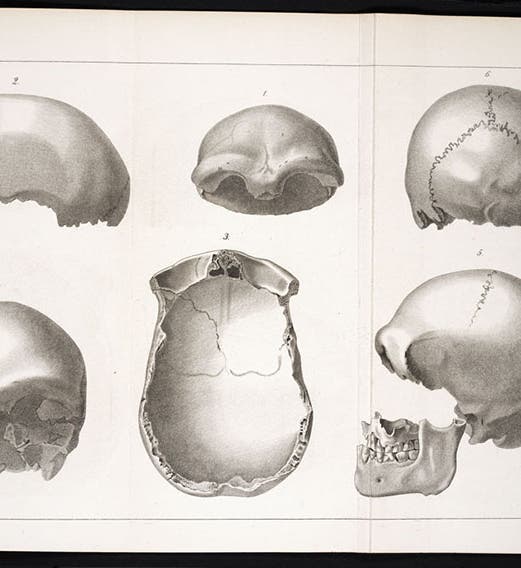

Schaaffhausen published a paper in 1858 on the find, "Zur Kenntniss der ältesten Rassenschädel” (“To the knowledge of the oldest human-race skulls”) in the Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und Wissenschaftliche Medicin, in which he argued for the great age of the Neanderthal specimen. He also included a plate showing different views of the skull cap (first image). (Fuhlrott made a similar argument the next year in a paper he published in a different journal, with different drawings of the cranium.) Traditionally, credit for discovering the first recognized Neanderthal specimen is given to both Fuhlrott and Schaaffhausen. Schaaffhausen's attribution of a great age to Neanderthal was opposed by many, especially Rudolf Virchow, probably the most respected professor of the life sciences in Germany, who thought it likely that the Neanderthal specimen was a recent individual, pathologically deformed, and perhaps with legs bowed by a life riding horses. Many others agreed that it was not necessary to create a race of primitive humans to explain one set of aberrant bones. It would be some time before Schaaffhausen became a hero in the history of anthropology, at least in his native Germany.

Many in England – seeing no need to be deferential to Virchow – were interested in the find. George Busk took the trouble to translate Schaaffhausen's 1858 paper into English and publish it in the Natural History Review in 1861, providing new views of the Neanderthal cranium (we did a post on Busk last year, where you can see his illustrations). Thomas H. Huxley and Charles Lyell both included wood engravings of the Neanderthal skullcap in their well-received books of 1863, Huxley's Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature, and Lyell's The Geological Evidences of th Antiquity of Man. Evidence supporting Schaaffhausen's interpretation of Neanderthal emerged in 1864, when it was recognized that the so called "Gibraltar skull", found long ago in 1848, was quite similar to Schaffhausen’s Neanderthal skull, making Virchow's suggestion that the Neanderthal man was some sort of bow-legged Cossack horseman much more unlikely. Further discoveries of two more Neanderthal-like skeletons at Spy in Belgium in 1886 made it even more probable that Neandethal represented some kind of primitive, prehistoric human.

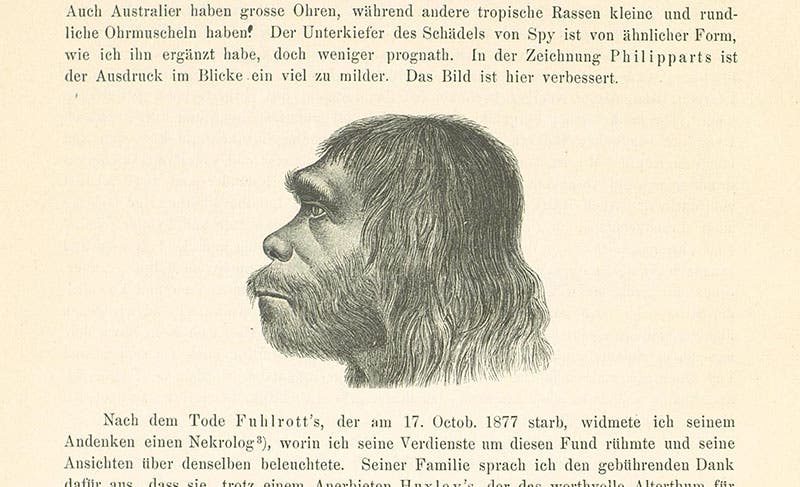

Schaaffhausen defended his view of Neanderthal as ancient for over 30 years. In 1888, after a description of the Spy skeletons was published, Schaaffhausen published a monograph called Der Neanderthaler Fund (The Neanderthal Find). We do not have a copy in our collections, but I found a German digital copy online, and I thought it worth mentioning, because it includes a drawing of a restored Neanderthal head and face (fourth image). For the next 80 years, Neanderthal would be the victim of many wild restorations that portrayed him as brutish and bestial. The drawing in Schaafhausen’s paper, on the contrary, presents a human forerunner who is indeed beetle-browed and hirsute, but who nevertheless looks lively and intelligent, seeming to be a worthy ancestor for modern humans, as Schaaffhausen thought he was.

Schaaffhausen was one of the founders of a provincial museum in Bonn in 1874, which grew into the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn, and that is where he deposited his Neanderthal partial skeleton. You can still see it there (fifth image), where it is now called Neanderthal 1, to distinguish it from the thousands of Neanderthal remains found since. The photograph above, from a very useful site called Don's Maps, was taken before a recent renovation of the Museum, but presumably Neanderthal 1 is still on display, laid out in a similar fashion.

I have heard it said that Schaaffhausen's career was dead-ended by his insistence on the antiquity of Neanderthal man and his resistance to Virchow. If so, you would never know it from his home, the Villa Schaaffhausen in Bad Honnef (sixth image), where he entertained visiting heads of state, and which was later given to the Archdiocese of Cologne by his daughter.

In our 2012 exhibition, Blade and Bone: The Discovery of Human Antiquity, we displayed the 1858-59 papers of both Fuhlrott and Schaaffhausen, as well as Lyell’s 1863 book that discussed and illustrated Neanderthal 1, Huxley’s 1863 book that also included Neanderthal, and the paper announcing the Neanderthal remains found at Spy in 1886.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.