Scientist of the Day - Hewett Cottrell Watson

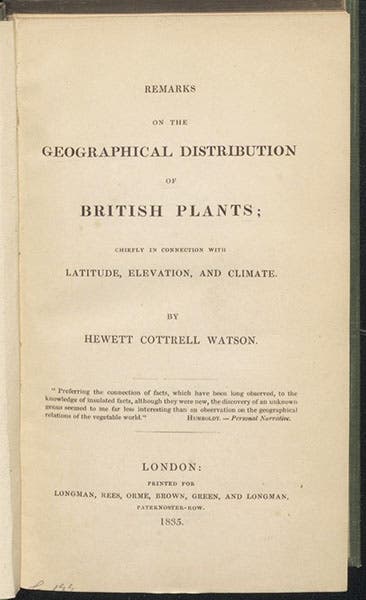

Hewett Cottrell Watson, an English botanist, was born May 9, 1804. Watson was what was called in Victorian England a “philosophical naturalist,” in that he was interested in explaining nature, rather than just naming, describing, and classifying organisms. His field was plants, more specifically, plant geography (phytogeography), and early in his career, just after finishing his education at Edinburgh, he privately printed a book, Outlines of the Geographical Distribution of British Plants (1832), in which he began to sketch out the locations of some 1400 species of plants in Great Britain. We do not have this work in our collections, but we have its second iteration, Remarks on the Geographical Distribution of British Plants (1835), in which he makes it clear that it is important to know not just the geographical location of every British plant, but its elevation range, the climate conditions under which it grows, the dates of earliest and latest flowering, and a host of other particulars. His hope was that, when we know where plants are, we will be able to figure out why they are there, and not somewhere else.

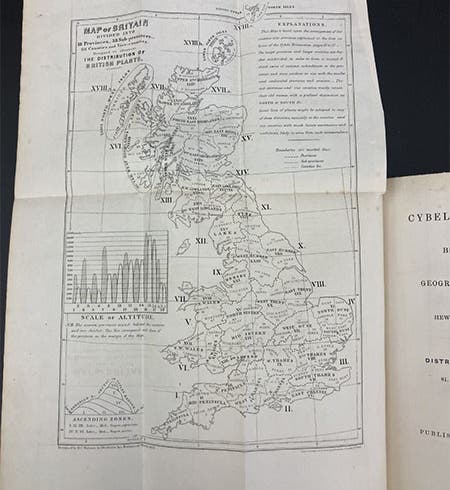

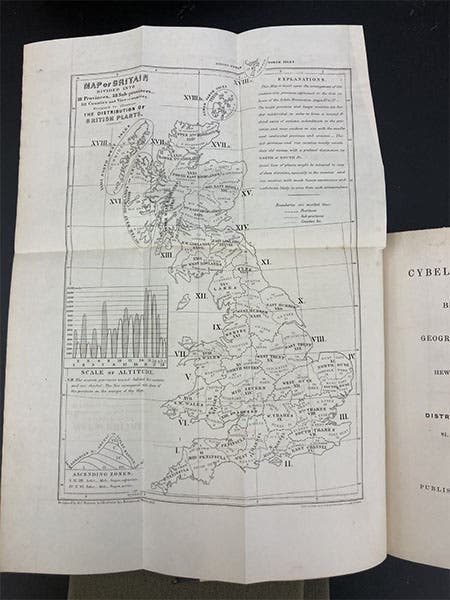

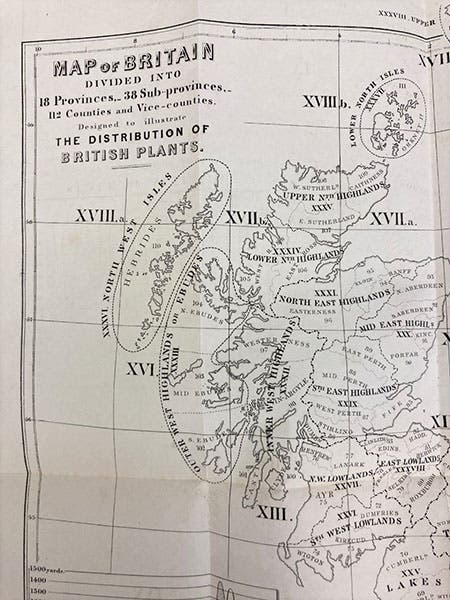

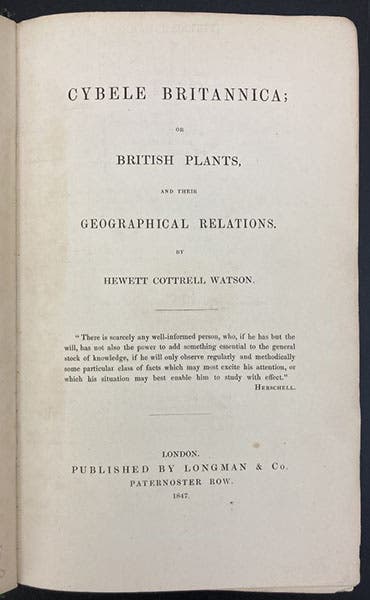

Watson took a career detour for about 6 years, pursing the study of phrenology and editing a phrenological journal (more about this below), but he returned to phytogeography in 1847 with the publication of the first volume of Cybele Britannica: or British Plants and their Geographical Relations (1847-59), which would eventually extend to 4 principal and 3 supplementary volumes, all of which we have in our collections, in their original cloth bindings. The bulk of the text is not very interesting to non-phytogeographers, but vol. 3 contains a map of the botanical provinces of Great Britain, and everyone likes maps (first image). Watson divided up the country into 18 provinces and 38 sub-provinces, in order to provide the basis for a nomenclature for plant geographers. We show here the entire map and a detail of the upper left corner, where some of the provinces and sub-provinces (and their relation to counties and vice-counties) can be more easily seen (fourth image, below).

Watson’s work soon came to the attention of Charles Darwin, who was avidly interested in plant distribution as he sought to find evidence for evolution by natural selection, and the two exchanged scores of letters in the 1850s. Watson had begun to doubt the fixity of species in the 1830s, and he later became convinced that plant species gave rise to other species as the conditions of life changed. He was not privy to Darwin’s private speculations about evolution, but when The Origin of Species was published in 1859, Watson read it and was an instant convert, and he wrote Darwin a letter, praising him as the “greatest revolutionist” of the century, if not of all time.

Watson, however, had a problem. In his professional exchanges with colleagues, he seldom behaved like a gentleman. He alienated just about everyone with his irascible behavior, even those who thought he was one of the brightest of the philosophical naturalists. His most notable breach of scientific etiquette came in 1847, in the first volume of Cybele, when he accused Edward Forbes, another respected philosophical naturalist, of plagiarizing his basic plant-zone system for Great Britain. Forbes had published a paper in 1846 in which he divided English plants into five floras, a variation on Watson’s six-flora system, without giving credit to Watson. Forbes had in fact appropriated Watson’s system, but he believed that by now it was public knowledge. He thought everyone knew that Watson was the supreme authority on plant distribution in Great Britain. Forbes probably should have given Watson credit for the basic system. But by the professional codes of the time, there were right ways and wrong ways to call attention to the fact that you felt your scholarly work had been slighted. And most definitely, the wrong way was to call someone a thief in print in a work available to the general public. Watson continued his attack on Forbes until Forbes’ premature death in 1854. As a result, he lost the friendship of many important botanists, such as Joseph Hooker. As time went on, Watson’s reputation faded, and he was little remembered by the time of his death in 1881. Only a century later would he be recognized as the greatest expert on British phytogeography of his day.

And now a few words about Watson’s interest in phrenology. Edinburgh was the hotbed of phrenological studies in the 1820s and 1830s, where Watson went to school. He joined the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1829 and edited the Phrenological Journal from 1837 to 1840. Phrenology has a disreputable reputation now, but it was quite respectable in the 1830s. After all, its fundamental premises were that brain function is localized, and that those localities can be identified by observation and experiment, and those certainly turned out to be worthy hypotheses. The bumps-on-the-cranium part turned out to be not quite so worthy. Other advocates of phrenology at the time were Robert Chambers, who wrote the evolutionary tract, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844), and John Pringle Nichol, author of a variety of popular books on astronomy. Only after 1850 would it be learned that most of the localized areas identified by phrenologists were incorrectly assigned, and phrenology rapidly dropped off in popularity among scientists (although it then rapidly gained popularity as a pseudo-science). Watson was one of the few advocates of phrenology to repudiate the discipline in his later years.

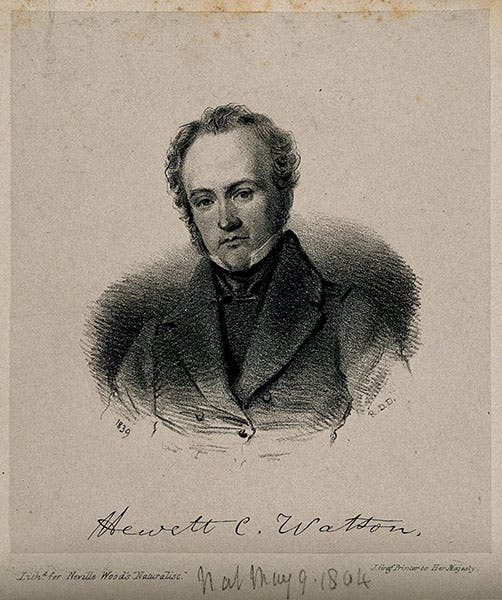

The portrait we use is a lithograph in the Wellcome Collection in London, printed in 1839 (second image). I must say, he does not look like a contentious man.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.