Scientist of the Day - Immanuel Velikovsy

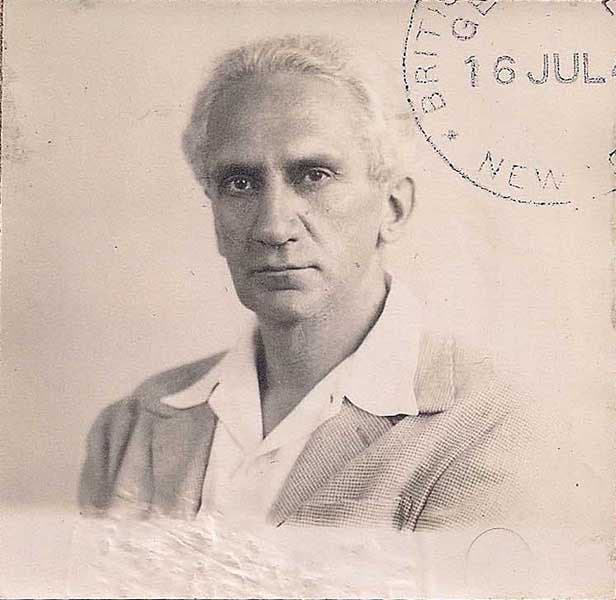

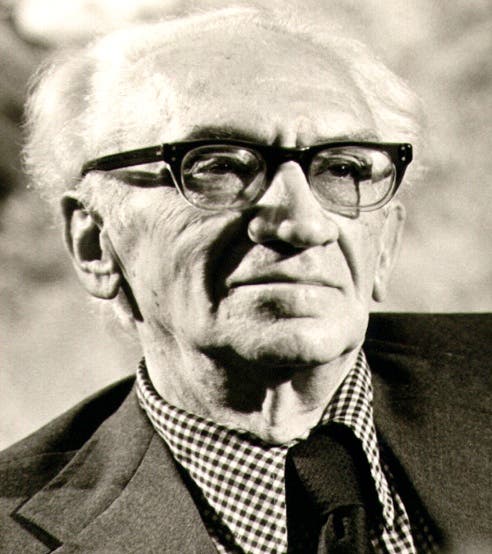

Immanuel Velikovsky, a Russian Jewish psychiatrist and would-be scholar, was born June 10, 1895, in what is now Belarus. Velikovsky came to world attention in the spring of 1950, when he published a book called Worlds in Collision. Velikovsy had spent many years studying ancient mythology, immersing himself in stories from Nordic, Mayan, Chinese, Indian, and Babylonian cultures, as well as accounts found in Hebraic sources, especially the Book of Exodus. He found that all these cultures had handed down stories about heavenly battles, massive floods and earthquakes, crop disasters, the raining down of matter, including fire, from the skies, and radical changes in the length of the day. He concluded that such similar tales from all these separate and distinct cultures must reflect real events, and he offered this scenario: Sometime around 1500 B.C., Jupiter ejected from within a large comet. The comet passed near the earth, tilting it on its axis and briefly stopping its rotation, while its hydrocarbon tail swept across the planet and rained down carbohydrates (manna) on the tribes of Israel who were fleeing Egypt, while also creating a passage through the Red Sea. The comet then settled down into orbit around the Sun, becoming the planet that we call Venus. There was more to it, but this summary will do for our purposes.

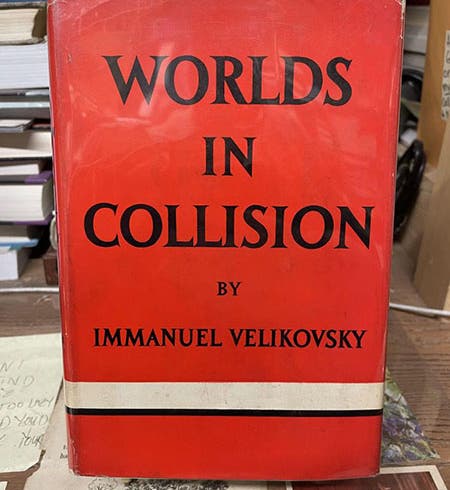

The surprise was not that Velikovsky found a publisher for his book – Charles Fort and Ignatius Donnelly had had no problem getting published – but that the publisher was Macmillan. Macmillan was the foremost publisher of science books in the United States, especially textbooks. So by accepting the manuscript of this unknown, first-time author for publication, Macmillan gave it an imprimatur of some stature.

Scientists – especially astronomers – were generally appalled by Worlds in Collision. They had no problem with the arguments from comparative mythology, but the physics was impossible. Celestial mechanics was a very precise science in 1950, and there was absolutely no way that Jupiter could spit out a comet – a comet 1000 times larger than comets were known to be – that blasted by Earth and briefly stopped its rotation, and then settled down into a nearly circular orbit around the Sun,leaving Jupiter unperturbed. It was utter nonsense to a physicist or an astronomer. Velikovsky’s view was that if the evidence was there in ancient texts, then the physics was wrong, and physics would have to accommodate itself to a truth derived from ancient literature. It is no surprise that two such different world views should clash, and clash strongly. Scientists who reviewed the book were unsparing in their denunciation of the scientific part of Velikovsky's book.

But their denunciation of Macmillan was far more heated. Several scientists, including Harlow Shapley, the dean of American astronomers at Harvard, wrote Macmillan even before publication, suggesting that they withdraw as publisher (a summary of the upcoming book had been published in January of 1950 in Harper’s Weekly). When the book appeared as scheduled, the criticism of Macmillan crescendoed. Many scientists were incensed that Macmillan included Worlds in Collision in their Science catalog for the spring of 1950, rather than labelling it comparative literature. Scientist wrote letters to Macmillan, pointing out that it would be hard to trust Macmillan's scientific textbooks if the editors thought that Velikovsky was a scientist. Some threatened a boycott of Macmillan if they did not disavow the book. Although the number calling for a Macmillan boycott was not large, it was enough to scare the publisher, and they soon decided that it would not violate the terms of their contract with Velikovsky it they turned publishing rights over to Doubleday, which did not have a textbook division. And that is what happened. Our Library’s copy of the book, a later printing, but still 1950, has the Doubleday imprint.

The disparagement of Velikovsky’s book by scientists was great publicity, and World’s in Collision became a best seller, and would remain popular for 30 years. The battle over the book was the first engagement in what Michael Gordin has called the “Pseudoscience Wars” (in his book The Pseudoscience Wars: Immanuel Velikovsky and the Birth of the Modern Fringe, 2012). Worlds in Collision was widely read, discussed, and embraced by the counterculture of the 1960s, and used to attack the intolerant elitism of the scientific establishment. I first read the book in the late 1960s, and I remember being awed and impressed by the argument from comparative mythology (a subject of which I knew nothing) and scornfully amused by the celestial mechanics (physics being my undergraduate major). I remember being particularly struck by the presumption that hydrocarbons are equivalent to carbohydrates. But I could well understand how someone untrained in either discipline might be in awe of Velikovsky’s scholarship and unswayed by the criticism of experts. The real surprise is that the entire controversy, so heated for three decades, suddenly dissipated, and the figure of Velikovsky, as an anti-authority hero, abruptly disappeared. You can review the entire war, its denouement, and the implications the story has for our own culture, in Gordin’s book, which I highly recommend.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Columbine, hand-colored woodcut, [Gart der Gesundheit], printed by Peter Schoeffer, Mainz, chap. 162, 1485 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3829b99e-a030-4a36-8bdd-27295454c30c/gart1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)