Scientist of the Day - Isaac M. Singer

Patent model for Isaac M. Singer's patent application for his sewing machine, patent granted Aug. 12, 1851, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution (author’s photo)

Isaac Merritt Singer, an American inventor and businessman, died July 24, 1875, at age 63. Singer was abandoned by his divorced mother when he was 12, so he ran away with a troupe of actors for some years. He had an inventive mind, and sold the rights to a miners’ drill to give him his first financial independence, after which he went back on the acting trail. But by 1849, he was in Boston, trying to perfect and sell a device for carving wood-blocks for printers, where he stumbled into the rapidly growing world of sewing machines manufacture.

Elias Howe had invented and had the patent on a lock-stitch mechanism for a sewing machine, which every machine needed, but otherwise there were dozens of variations in the shape of the needle, how it moved, how tension was maintained, how the cloth was fed, and how a machine was powered, and there were dozens of machines on the market in 1850. Singer developed his own machine, which used a straight needle moving vertically on a horizontal surface, and received a patent on Aug. 12, 1851. His patent model survives and is on display in the Old Patent Office Building in Washington, D.C. (first image), which sounds appropriate, except that the building now houses the National Museum of American History and the National Portrait Gallery, both part of the Smithsonian Institution. I ran across the model unexpectedly in 2017 and snapped a photo; it was not far from the over-the-top portrait of Singer in the NPG (second image).

I. M. Singer & Co. showroom, wood engraving, 1857, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Aug. 29, 1857, Smithsonian Institution photo 48091-B (www.si.edu)

As soon as he began manufacturing his own sewing machines, Singer was sued by Howe, and Singer had to go into partnership with a lawyer, Edward Cabot Clark, who had helped Singer get his patent, and who now had to deal with Howe. Clark was the real genius behind the success of I.M. Singer & Co.; he came up with the idea of selling door-to-door and allowing buyers to pay in installments, which was a novelty in American business economics at the time, and he also set up showrooms in New York City where prospective customers could be coddled and exposed to the wonders of Singer machines (third image).

The other brilliant mind behind the success of Singer was Orlando Potter, who was the head of a rival sewing machine manufacturer, and who suggested in 1856 that the major players in what was now a “sewing machine war” pool their patents into what was called the Sewing Machine Combination, so they could quit suing each other at great expense, and they convinced Elias Howe to accept a small payment for each machine sold. The litigious age for sewing machines was over.

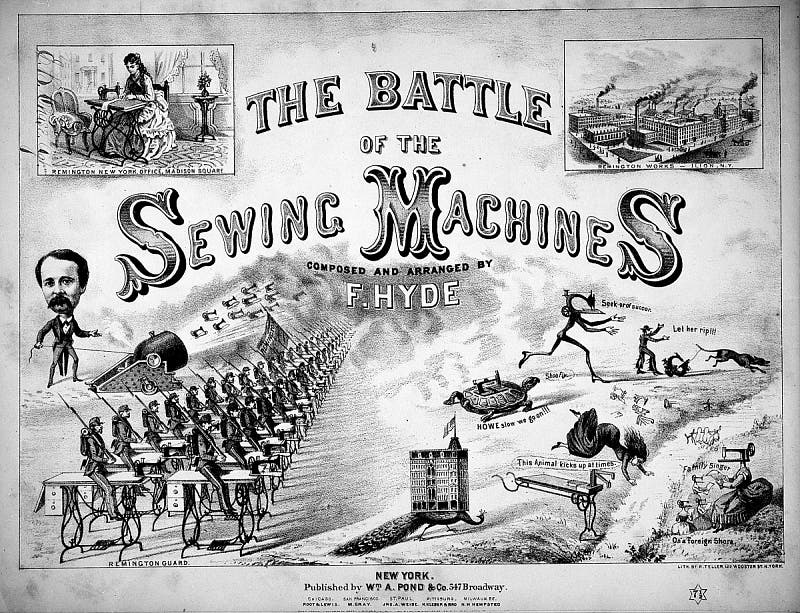

"The Battle of the Sewing Machines", lithograph, 1874, showing new Remington machines driving out machines of Singer, Howe, Wilcox and Gibbs, and others, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution (www.si.edu)

The Smithsonian Libraries has a piece of sheet music for "The Battle of the Sewing Machines," apparently written in commission from the Remington Corporation in 1874, showing an army of Remington sewing machines vanquishing the ill-equipped forces of Howe, Wilcox and Gibbs, Singer, and others. Out of curiosity as to the real aftermath of this apparently one-sided battle, I checked the figures. In 1875, one year later, Remington sold 25,000 machines, a respectable number, about what Howe sold. However, that same year, the Singer company sold 250,000 machines, about ten times more than anyone else. Singer would dominate the trade for decades.

However, Isaac had nothing to do with any of his company's subsequent success. He was forced out in 1863, when his initials were removed from the company logo, and he moved to Europe, which is where he must have run across American-in-Paris painter Edward Harrison May, who did his portrait (second image).

Singer seems to have been generally unlikeable, except to the 4 or 5 women, with whom he fathered at least 24 children, most of whom inherited sizeable fortunes. Singer is the kind of individual whom I usually avoid profiling, since, in my opinion, he doesn't deserve to be remembered. But since the Singer company succeeded despite, rather than because of, Singer’s contributions, we make an exception today.

The sales figures we quoted, and our third image, were drawn from an excellent book, The Invention of the Sewing Machine, by Grace Rogers Cooper, published by the Smithsonian Institution back in 1968. We have the work in our Government Documents Collection.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.