Scientist of the Day - J.L.E. Dreyer

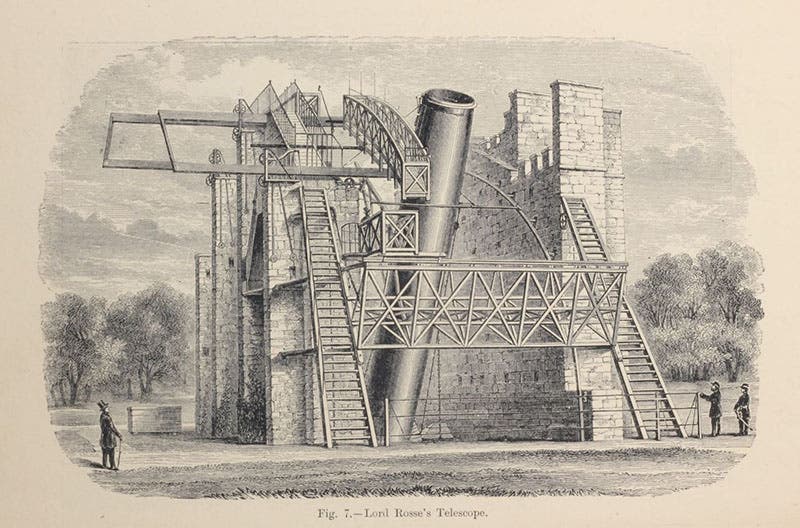

John Louis Emil Dreyer, a Danish/English astronomer who is almost always referred to as J.L.E. Dreyer, died Sep. 14, 1926, at age 74. Dreyer was born in Copenhagen and studied astronomy at the University there; in 1874, he moved to Ireland, and he would spend his next 42 years there. He first got a job as an assistant to Lawrence Parsons, the 4th Earl of Rosse, who owned a famous observatory at Birr Castle in Parsonstown, in central Ireland. Parsons' father, William, the 3rd Earl, had built a mammoth 72-inch reflector at the family castle in the 1840s, and had used it to discover the spiral nature of some nebulae. We show the Leviathan of Parsonstown, as it was called, in our third image; you can learn more at out post on William Parsons.

In 1878, Dreyer moved on to another Irish observatory, this one at Dunsink, near Dublin, where the observatory for Trinity College, Dublin, was located (fourth image). The observatory was directed by Robert Stawell Ball, a soon-to-be noted author of works on popular astronomy.; it had been directed before that by William Rowan Hamilton, inventor of quaternions. We have written a post on Ball and a post on Hamilton. Dunsink was over 100 years old when Dreyer got there; its principal observing instrument was a 12-inch refractor built by Thomas Grubb and installed in 1862. It sits in its own dome (see fourth image) and is called the South telescope, not because it is south of the main observatory (although it may be), but because it was donated by British astronomer James South.

In 1882, the director of the Armagh Observatory, the third of the venerable Irish observatories, retired, and Dreyer was hired to replace him, and Dreyer would be at Armagh for the next 34 years. Armagh, located in Northern Ireland, had been founded in 1789, and had an excellent telescope, a 15-inch reflector built by Thomas Grubb and installed in the 1830s. Dryer soon added another, a 10-inch refractor, also built by Grubb (now the firm of Grubb Parsons), which is still there, and still quite handsome, as you can see here.

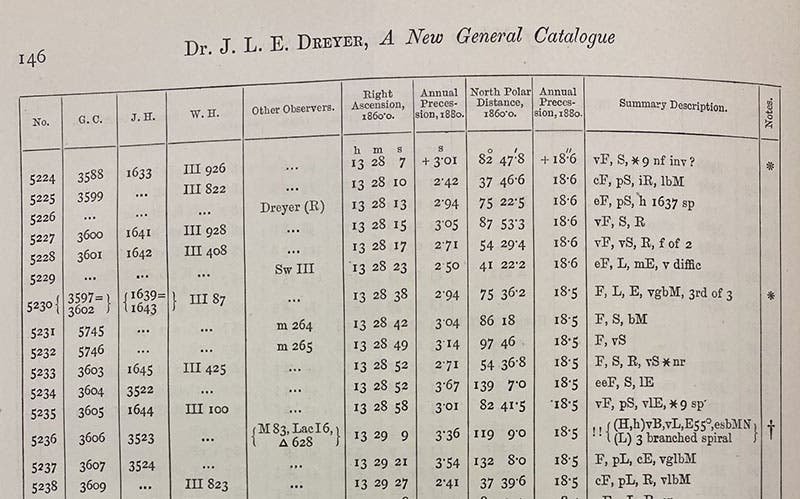

By this time, Dreyer was focused on compiling a new catalog of nebulae, to bring those of William and John Herschel up to date. Dreyer published this catalog in a volume of the Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1887-89, and it is still the standard reference work for nebulae. The prefix “NGC” denotes an object from Dreyer’s catalog, just as “GC” indicates an object from John Hershel’s 1864 catalog, compiled from his father William’s observations. We show you the top of one page of Dreyer’s catalog (fifth image), and near the bottom, you can see the entry for nebula no. 5236 (NGC 5236). In the fourth column, Dreyer indicated that this is also known as M83 (Messier 83). And at the far right, that column begins with two exclamation points, indicating that this is a splendid object to view. If you look up M83 or Messier 83 on Wikipedia, the article will immediately tell you that this is the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, NGC 5236. NGC numbers are a regular feature of any article on or catalog of nebulae to the present day.

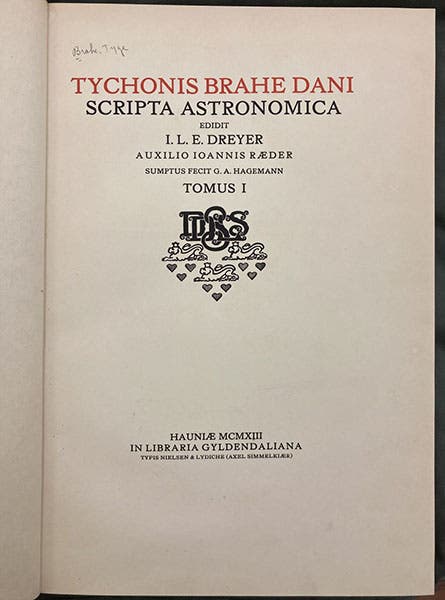

Dreyer also distinguished himself as a historian, for which he had no training, but who did back then? Being from Denmark, he had always been fascinated by the most distinguished of all Danish astronomers, Tycho Brahe, and in 1890, he published a biography of Brahe. For some inexplicable reason, our Library has never had a copy of the first edition of Dreyer's biography, but that lacuna gives me an excuse to show the 1963 Dover reprint of Dreyer's book, with its photo of Tycho's gravestone on the cover (sixth image). Having rekindled an interest in Brahe, Dreyer then undertook the publication of the complete works and correspondence of Brahe. Tycho Brahe Dani Opera Omnia began to see the light in 1913, with the publication of the first volume (seventh image), and wrapped up in 1929 (15 vols. in 17 parts), three years after Dreyer's death. We do have this set in our collections (and even though it is bound in green buckram, it is still a nice-looking set). This is not an edition of translations, but rather a reprinting of the original works, almost entirely in Latin.

Front cover, Tycho Brahe: A Picture of Scientific Life and Work in the Sixteenth Century, by J.L.E. Dreyer, orig. publ. 1890; this paperback ed., 1963 (author’s collection)

Dreyer also wrote A History of the Planetary Systems from Thales to Kepler (1905), which was also reprinted (under a slightly different title) by Dover Publications in the 1960s. When I studied Brahe and Kepler in graduate school, this was still a standard text.

Dreyer moved with his wife to Oxford in 1916, after retiring from Armagh, to work on Brahe's Opera, and he lived there until his death. He was buried in Wolvercote Cemetery in Oxford. You may see his gravestone here.

I find it interesting that there is an active movement in Ireland to have its three founding observatories at Birr Castle, Dunsink, and Armagh, designated as a single World Heritage site. These are the three observatories where Dreyer carved out his distinguished career. I hope his name figures prominently in the application. It wouldn’t hurt.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.