Scientist of the Day - J. Robert Oppenheimer

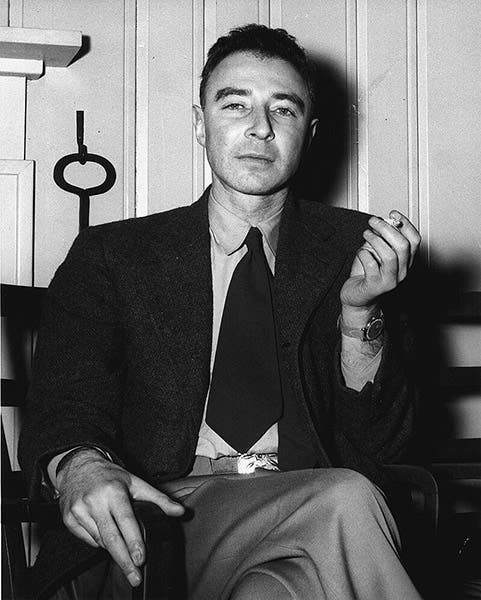

J. Robert Oppenheimer, an American theoretical physicist, was born Apr. 22, 1904. Oppenheimer was a gifted mathematician who came of age during the rise of quantum mechanics in the 1920s, indeed, he took an active role in its success, studying in Germany with Max Born and writing his first important papers when he was barely in his twenties himself. When he returned home, he was eagerly sought by many universities; he chose the University of California at Berkeley, which allowed him to share his time with Caltech in Pasadena. He was a superb seminar teacher and produced many excellent students.

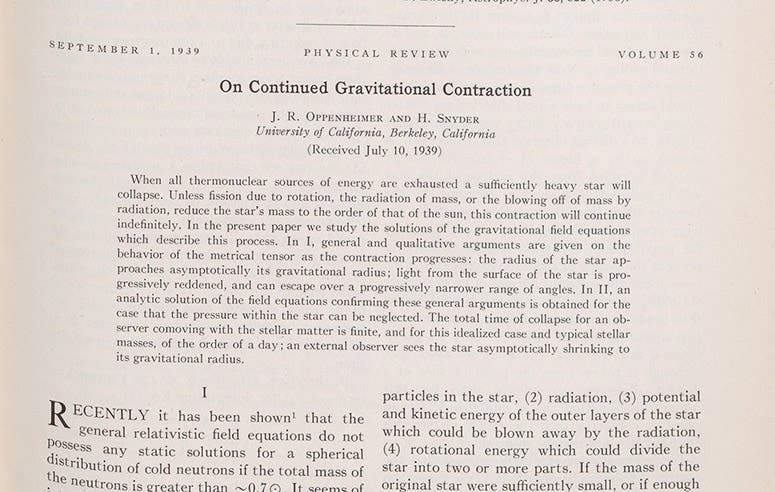

In the late 1930s, about the time his friend Hans Bethe at Cornell was writing his "bible" on nuclear physics and explaining how the sun produces energy, Oppenheimer developed his own interest in astrophysics and the workings of stars, and he published 3 papers with various students in 1938-39 that predicted the existence of neutron stars. In the last one, he demonstrated that neutron stars of a certain size would collapse catastrophically and without limit (see third image, below). It was the first modern paper to predict mathematically the existence of black holes, 155 years after John Michell posited black holes in a more general way.

Detail of first page of article by Robert Oppenheimer and Hartland Snyder, in which the existence of black holes is predicted, Physical Review, vol. 56, p. 374, 1939 (Linda Hall Library)

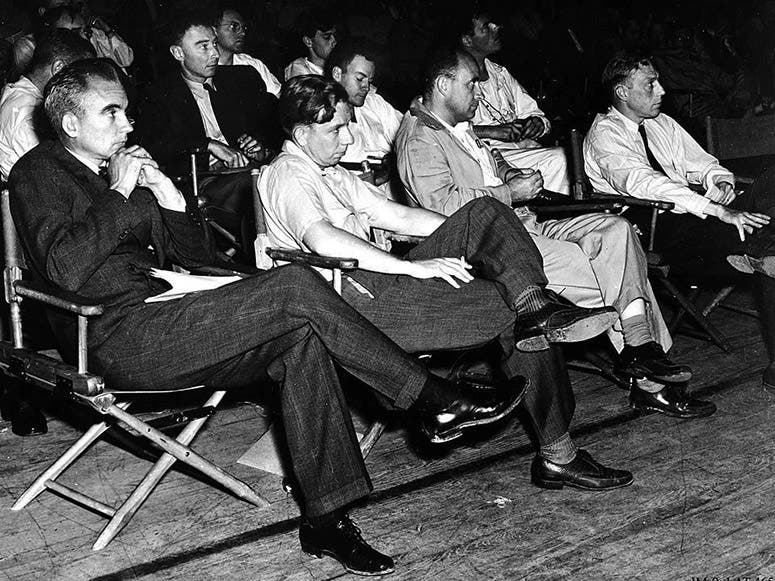

In the fall of 1941, after the United States was informed by the British that it might be possible to build an atomic bomb, and that the Germans could be working on just such a project, President Roosevelt established a committee headed by James B. Conant to coordinate an American atomic bomb effort, even before the U.S. entered the war. Conant knew Oppenheimer and put him in charge of a difficult calculating project, in which many of Oppenheimer's students became involved. The Manhattan Project to develop at atomic bomb was established in June of 1942, and U.S. Army General Leslie Groves was placed in charge, concerned mainly with logistics. To head up the scientific team, he chose Oppenheimer. No one is quite sure why he made that choice, since Oppenheimer, although brilliant, had no leadership experience at all. But the choice was truly inspired. Oppenheimer proved to be a master at assembling and directing a large scientific team of unconventional geniuses such as Richard Feynman. Much of his success can be attributed to the fact that he understood immediately the physics of every problem that arose, and thus knew what had to be done to solve the problem and who was best able to solve it. People on his team such as Bethe and Feynman, future Nobelists both, had nothing but praise for Oppenheimer's intellect, his ability to get to the root of a problem, and his skill at handling sometimes difficult prima donnas like Edward Teller.

The Manhattan Project was a great success, setting up plants to produce plutonium and enriched uranium at Hanford, Washington, and Oak Ridge, Tennessee, respectively, with the design team located at Los Alamos, New Mexico. There was no precedent whatsoever for a nuclear weapon, so people like Feynman and Bethe and their colleagues had to figure it all out on paper, and they did so. The plutonium bomb was successfully assembled and tested at the Trinity site in New Mexico on July 16, 1945. The bombs targeted for Hiroshima and Nagasaki were dropped three weeks later.

Oppenheimer was not happy with Truman's decision to drop the second bomb on Nagasaki, thinking it unnecessary, and he became increasingly wary of the push to develop more and more powerful nuclear weapons. He was especially opposed to working on the "Super," a hydrogen fusion bomb, for which Teller was the principal advocate. Oppenheimer finally left Los Alamos in 1947 to take over the Institute for Advance Study at Princeton, where Albert Einstein was the most famous resident, and where Oppenheimer excelled at attracting talent, such as the young Freeman Dyson.

When the Red Scare movement arose in this country in the early 1950s, Oppenheimer was a prime target. His politics were left-wing; he was a socialist, and many of his friends from the 1930s had been Communists. He had an interest in un-American topics such as Eastern philosophy, and religions such as Hinduism – he had even quoted a passage from the Bhagavad Gita at the Trinity test in 1945. He had been under surveillance by the FBI since even before the War. Finally, in 1954, in a reprehensible decision, he was stripped of his security clearance by the Atomic Energy Commission and effectively shut out of cutting-edge nuclear research. It was a low-point in government-science relations, and certainly an ungrateful act toward a man who had been absolutely essential in the success of the Manhattan Project. Edward Teller testified against Oppenheimer at the AEC hearings and was never forgiven by the scientific community. Oppenheimer was forgiven when he was awarded the Enrico Fermi Award in 1963 by President Kennedy (presented by President Johnson), in an act of official apology for a government that had behaved badly. It came none too soon, as Oppenheimer died, of lung cancer caused by his incessant smoking, in 1967. He was only 62 years old.

I have seen the film Oppenheimer (2023), but it was several years ago, and I did not rewatch it for this post. I do remember thinking that Cillian Murphy, much to my surprise, gave an excellent performance as Oppenheimer.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.