Scientist of the Day - Jacob Wortman

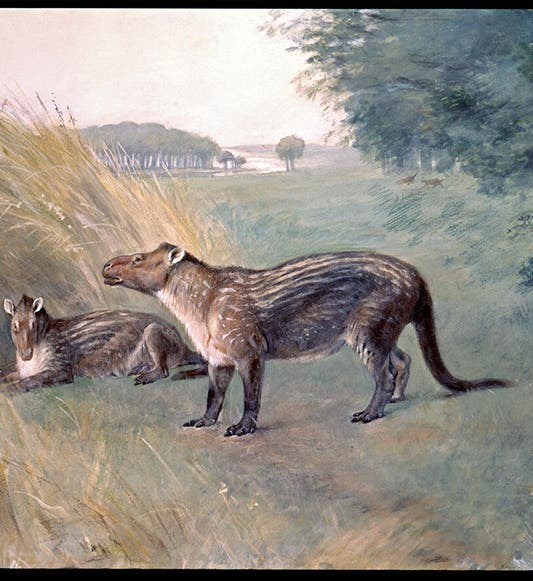

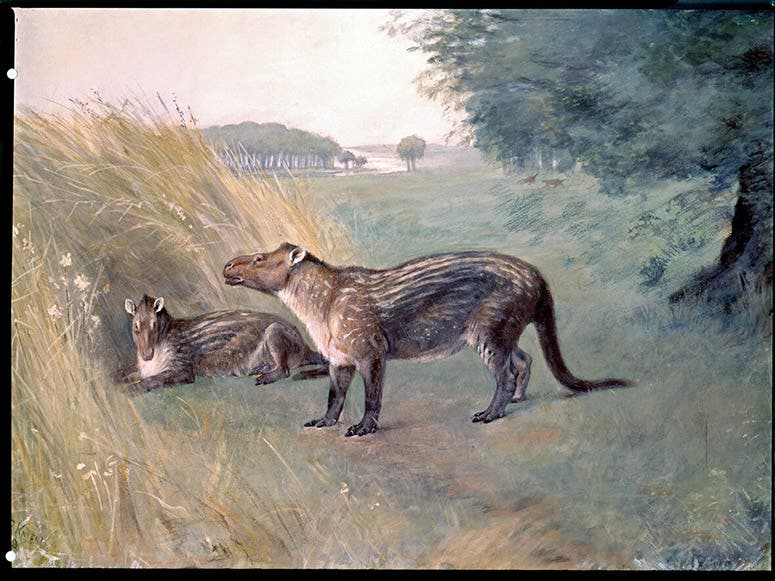

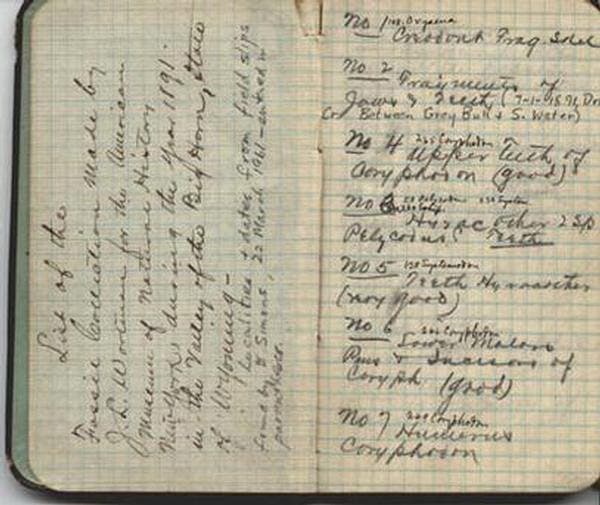

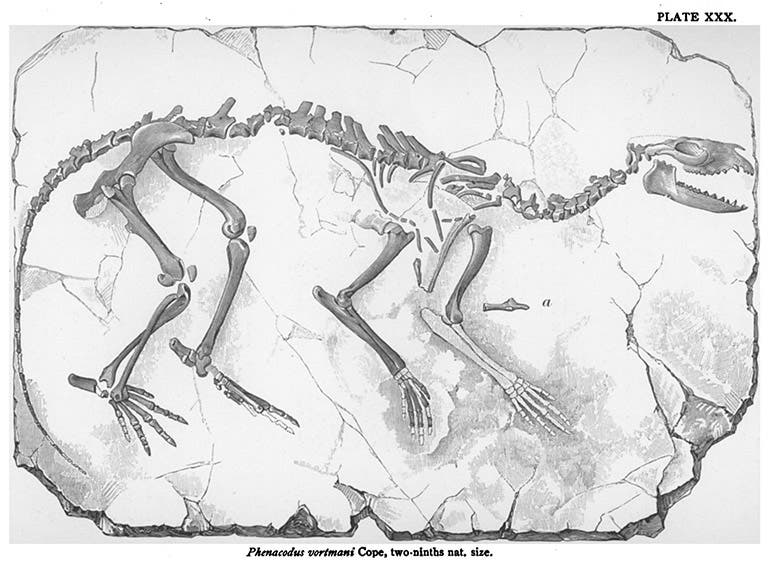

Jacob L. Wortman, an American fossil hunter, died June 26, 1926, at age 69. Wortman came from Wyoming, attended Oregon State University in Eugene, and met a professor interested in vertebrate fossils who kindled a similar interest in Wortman. So Wortman dropped out of school and was off to hunt fossils. He was hired by Charles H. Sternberg of Kansas for two of his expeditions, where he proved himself an adept fossil hunter, excavator, and preparator of specimens. Sternberg was working for Edward D. Cope of Philadelphia, a wealathy professor of paleontology who paid well for specimens from Western badlands. Wortman went to work directly for Cope, and remained on his retainer throughout the 1880s. His special interest was not dinosaurs but early mammals – he had a keen eye for their tiny fragments – and he found hundreds of specimens representing scores of new species, mostly from the Paleocene and Eocene epochs, 65-50 million years ago. Cope would describe and name these back in Philadelphia; sometimes he would give Wortman credit, as he did with Phenacodus, a primitive Eocene ungulate, a species of which he named after Wortman (first and second images). But usually Wortman got little credit, and he was never allowed to name and describe his own finds.

Fossil skeleton of Phenacodus vortmani, a primitive Eocene ungulate, found by Jacob L. Wortman and named and described by Edward D. Cope, American Naturalist, vol. 18, 1884 (Linda Hall Library)

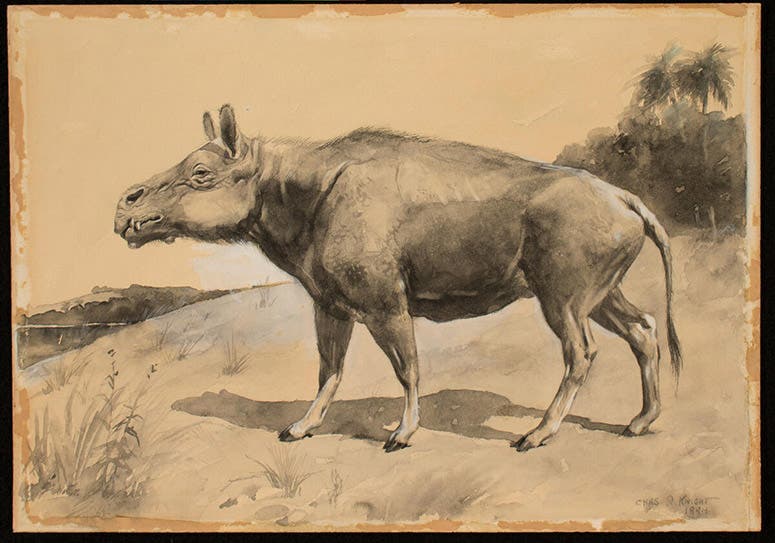

Perhaps tiring of his forced anonymity, Wortman left Cope in 1891 and went to work for the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), eventually for Henry Fairfield Osborn, their lead paleontologist. Wortman wanted to hunt mammals, but the Museum wanted dinosaurs, so Wortman was sent in pursuit of Brontosauri, not Eohippi. His most notable achievement at the AMNH may have been asking the young and unknown artist Charles Knight to do a life restoration on paper of an Elotherium (now Entelodon), a Eocene omnivore somewhat like a hippo with a boar’s head, one of the many early mammals Wollaston had unearthed. Knight completed his painting (third image) and showed that he had an unusual ability to bring prehistoric animals to life. Knight was off and running on a career that would be much more distinguished than Wortman’s. In 1898, he painted Wortman’s Phenacodus, bringing to life Wortman’s discovery in a way that Wortman never could (first image).

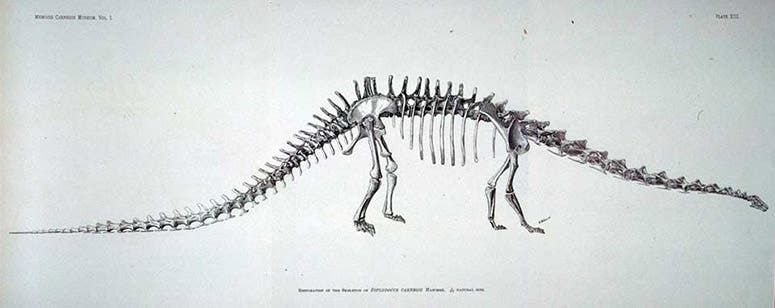

Wortman apparently did not get along with Barnum Brown, Osborn’s other featured dinosaur hunter at the AMNH, so when the new Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh asked Wortman in 1899 if he wanted to jump ship and join their team, he accepted their offer. He must have known that they were going to send him out after dinosaurs, not mammals, which is precisely what William J. Holland, their new director, did. Holland wanted a spectacular dinosaur to please his own boss, Andrew Carnegie, and he sent Wortman out to Wyoming to find one. Wortman promptly did just that, his team unearthing a nearly complete skeleton of a new species of sauropod, which was named Diplodocus carnegeii, after Carnegie, not Wortman (fourth image). It became the signature dinosaur of the Carnegie Museum, and Carnegie was so pleased that he commissioned replicas and distributed them to museums around the world, including the British Museum in London. You can read about the British Museum Diplodocus in our exhibition catalogue, Paper Dinosaurs.

But Wortman was not around to enjoy the success of Diplodocus carnegeii. In 1900, because of some perceived slight or misfeasance of duty, he demanded that a member of the staff be fired; when Director Holland refused, Wortman abruptly resigned. He moved on for a while to the Peabody Museum at Yale. After a few years of desultory work there, he resigned again, and gave up fossil hunting entirely. He moved to Brownsville, Texas, opened a drugstore, and for the last twenty years of his life, as far as we know, never looked at another fossil or even read about them. This was strange behavior for an accomplished fossil hunter. As Holland put it in his obituary for Wortman, “It was a curious act of renunciation, the psychology of which is hard to explain.” It remains a mystery to this day.

Group portrait of four field workers from the American Museum of Natural History; Jacob Wortman is second from left, 1895, reproduced in Edwin H. Colbert, Men and Dinosaurs, plate 43, E.P. Dutton, 1968 (author’s copy)

Photos of Wortman are hard to come by; I found no individual portraits, and only several group portraits in which Wortman made a usually sullen appearance. I show you one of those (fifth image), taken in the field in 1895, where Wortman is second from the left, and which also includes Walter Granger, a former post subject. Perhaps he is disgruntled because he is being asked to look for dinosaurs, not mammals. The AMNH has one of Wortman’s notebooks (probably more than one) from his first field expedition for the museum, which you can leaf through online on a very clunky webpage. It is not very thrilling, but he does mention there finding many of the mammal specimens that established his reputation. We reproduce here the first two pages (sixth image). The page written vertically at the left identifies the notebook as one kept by Jacob L. Wortman listing the fossils found in the Valley of the Big Horn in Wyoming during the 1891 season.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.