Scientist of the Day - Jacobus Henricus van ‘t Hoff

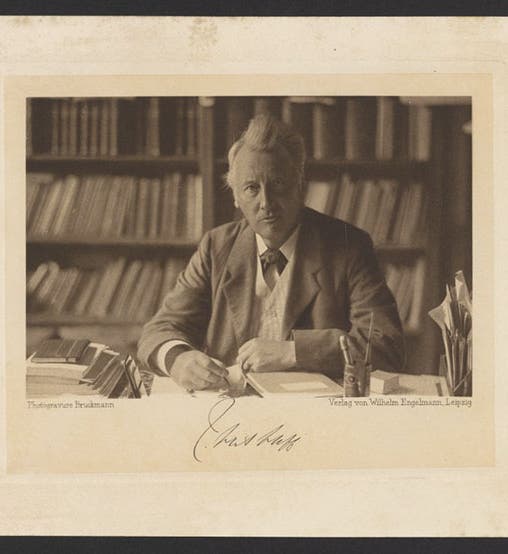

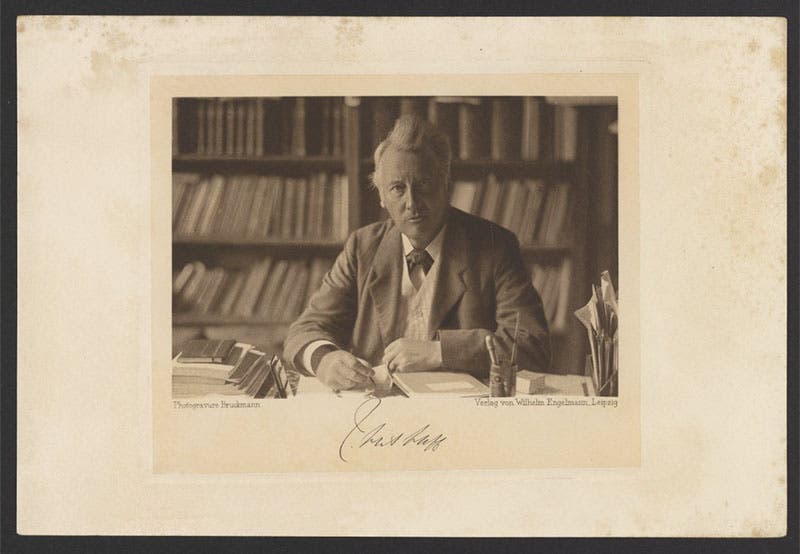

Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff, Jr., a Dutch chemist, was born Aug. 30, 1852, in Rotterdam. He studied chemistry in Delft and Leiden, spent a year with August Kekulé in Bonn, and another in Paris. Just before he received his doctorate at Utrecht in 1874, he published a small 11-page pamphlet that would dramatically alter the approach taken by chemists in their attempts to unravel the structure of chemical compounds.

Chemists by 1874 had worked out the chemical formulae of scores of molecules involving carbon. It was known that carbon was tetravalent, meaning that carbon would bond with four hydrogen atoms or other combinations of atoms that involved four bonds. But chemists tended to visualize molecules in two dimensions, imagining that a carbon molecule could be spread out on a piece of paper, with bonds going in various directions in the plane of the paper. But such two-dimensional models lacked explanatory power – they predicted many more isomers (structural variants) than Nature provided. Moreover, two-dimensional models could not explain optical activity, a property of many carbon molecules whereby the plane of polarized light is rotated right or left. Louis Pasteur had done some famous experiments in 1848 on the optical activity of tartaric acid.

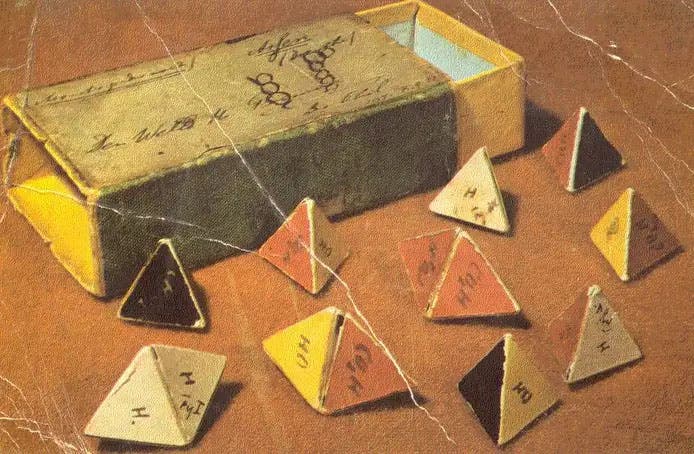

Van 't Hoff proposed in his pamphlet to extend chemical structure "into space." The full title of his booklet, translated from the Dutch, was: “Proposal for Extending the Currently Employed Structural Formulae in Chemistry into Space.” The next year, the pamphlet was greatly expanded and translated into French, but the title was shortened: La chimie dans l'espace (1875). Van ‘t Hoff suggested that the four atoms that bond to carbon occupy the four points of a tetrahedron, with the carbon atom in the center (see a modern diagram, second image). By extending carbon molecules into three dimensions, van 't Hoff realized that with four different bonding atoms, it was possible to build a molecule in two forms, with identical constituents but mirror-image structure, so that the two molecules could not be superimposed on one another. And no more than two mirror-image molecules were possible. The tetrahedral carbon atom did have explanatory power. Our word for “chemistry in space” is stereochemistry. That science was born in 1874, with van ‘t Hoff’s 11-page paper.

A French chemist, Joseph Achille Le Bel, also proposed the tetrahedral carbon atom in 1874, and van ‘t Hoff always gave him due credit in his later editions. But Le Bel never did anything further in stereochemistry, although he continues to be acknowledged as a co-discoverer of the tetrahedral carbon atom.

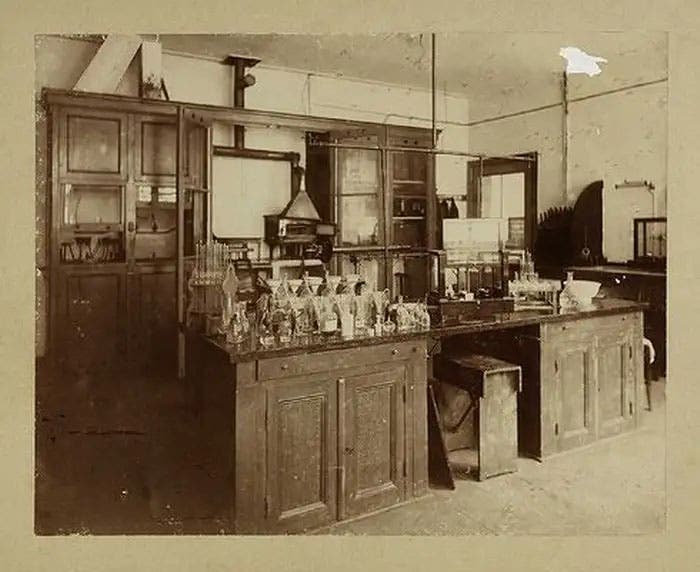

Van ‘t Hoff taught at Amsterdam until 1896, and then was invited to Berlin to finish his career. He was awarded the very first Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1901. Interestingly, he was not specifically rewarded by the Nobel committee for his work on the tetrahedral carbon atom; the prize rather was given “in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by the discovery of the laws of chemical dynamics and osmotic pressure in solutions”. Perhaps this wording is what allowed them to avoid splitting the Prize between van ‘t Hoff and Le Bel.

We do not have any of van ‘t Hoff’s early works on the tetrahedral carbon atom, which is too bad. I am sure the Voortel (the short title for the original 1874 Dutch pamphlet) is unobtainable, but copies of the French edition (1875) or the first German edition (1877) ought to be out there somewhere. We should look for one (we do have quite a few later editions of various van ‘t Hoff works, including an 1894 edition of “Chemistry in Space”). Perhaps we might also look for some of the cardboard models that van ‘t Hoff made to demonstrate his three-dimensional molecules (third image). EBay can have some surprising treasures.

Van ‘t Hoff died on Mar. 1, 1911, in Berlin, and is buried in the Berlin-Dahlem Cemetery there. There is a statue honoring van ‘t Hoff in Rotterdam, his birthplace.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.