Scientist of the Day - James Croll

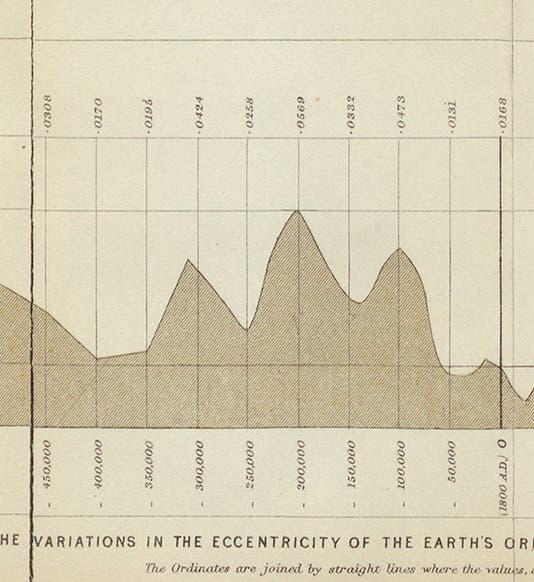

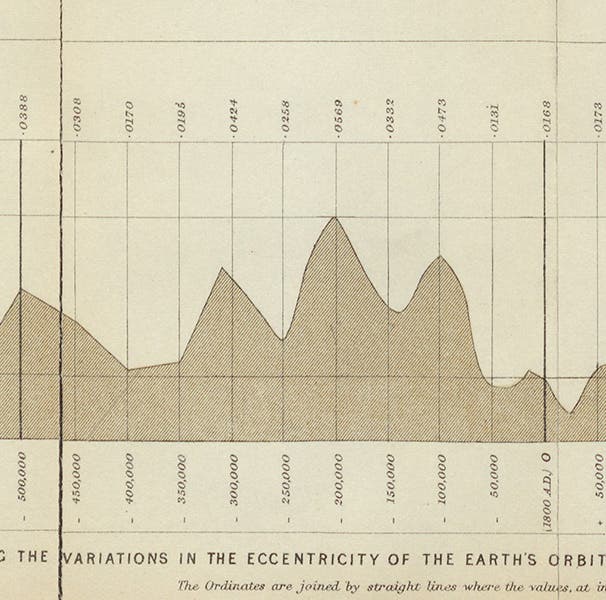

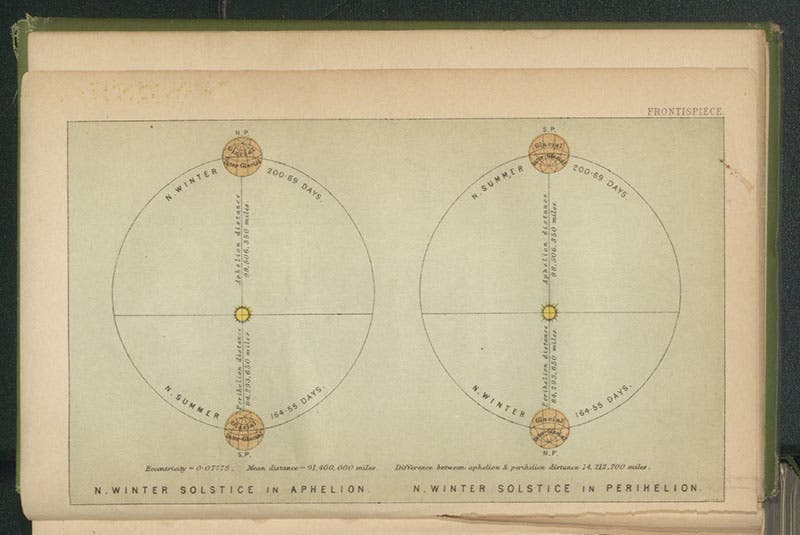

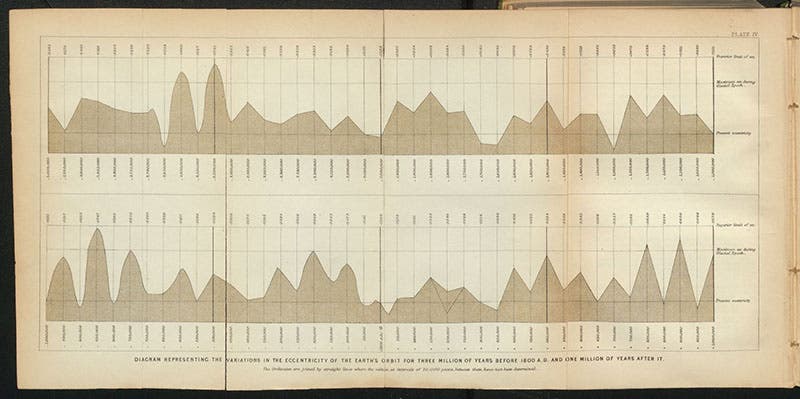

James Croll, a Scottish astronomer and climatologist, died Dec. 15, 1890, at age 69. In 1864, Croll proposed that ice ages were caused by changes in the orbit of the Earth. It had been known for centuries that the Earth's orbit slowly changes shape over time, going from more circular to more elliptical and back again over a cycle of tens of thousands of years. Moreover, the position of the winter solstice in the Earth’s orbit changes because of another cycle called the precession of the equinoxes. Croll wondered how these cycles might affect the earth's climate, and he demonstrated that when winter in the northern hemisphere occurs when the Earth is at aphelion (farthest from the Sun) during a time of high orbital eccentricity (when the orbit is most elliptical), then snow would accumulate in the northern hemisphere, which would in turn reflect more heat from the sun and make it even colder, and this feedback loop would eventually cause a sustained ice age. As the entire process is cyclic, this suggested that there had might have been multiple ice ages in the past, not just one, and Croll was able to provide numbers, predicting for example that there would be a 22,000-year cycle of ice ages during times of high orbital eccentricity. In a graph of the change of orbital eccentricity during the past 3 million years, the peaks represent probable periods of glaciation (sixth image; detail in first image).

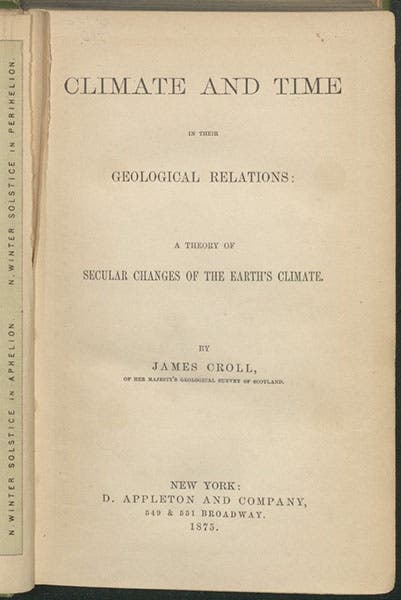

Croll communicated his initial results to Charles Lyell, who was the most eminent geologist in Victorian England. Lyell was intrigued by Croll's calculations, and he in turn introduced Croll to Archibald Geikie, the eminent Scottish geologist. Geike was equally captivated, and he hired Croll to work on the Geological Survey of Scotland, of which Geikie was director. With the backing of Lyell and Geikie, Croll published Climate and Time, in their Geological Relations, in 1875. The book was well received by geologists; for example, it was highly praised by James Geikie, brother to Archibald and a respected Scottish geologist who had just published his own book on the ice ages in Scotland. Croll would be elected a fellow of the prestigious Royal Society of London the next year, and would retire in 1880, because of health reasons, with an enviable reputation in geological circles. Even though many of his exact predictions were incorrect, he was nevertheless the first to demonstrate any kind of connection between changes in the Earth's orbit and climate change, and when more precise evidence of such connections was provided in the 1970s, Croll was singled out as the father of astronomical theories of climate change.

But none of this constitutes the most remarkable feature of Croll's career. His greatest feat, by far, was to overcome his low birth and lack of education and pull himself up by his bootstraps to become a respected scientist. The son of a farmer from a small Scottish hamlet, he started life as a wheelwright, then became, in turn, a tea shop owner, a hotel manager, an insurance agent, and a museum janitor. All the while, he taught himself astronomy and physics, and he was still working in the museum when he wrote to Lyell in 1864 and presented his climate-change theory. Lyell had no reason to pay him any attention, and neither had Geikie. But amazingly, they did, and moreover, they encouraged and supported Croll. Our fondness for rags-to-riches stories notwithstanding, this almost never happens in science, especially to someone who is well into middle age before anyone takes notice of his work. How Croll managed to pull this off, I do not know. Perhaps clues can be found in Autobiographical Sketch of James Croll, with Memoir of his Life and Work (1896), by James C. Irons, which we do not have in our Library.

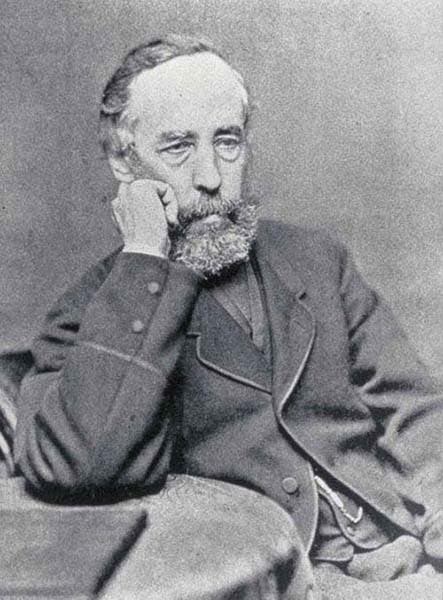

Not surprisingly, there is only one surviving portrait of Croll, a photograph taken late in life and published only after his death (second image). But we do have, in our History of Science Collection, a copy of Climate and Time (the New York edition of 1875), from which we drew the images for this post. We also have two later books by Croll.

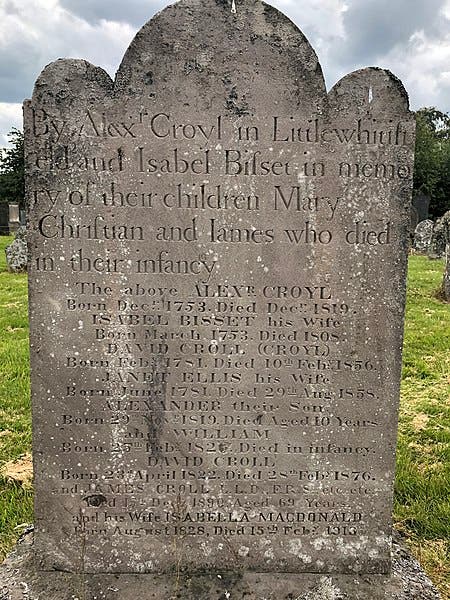

Croll was buried in the family plot in Cargill, Ireland, where there was barely enough room at the bottom of the headstone to accommodate the names of James and his wife Isabella (seventh image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.