Scientist of the Day - James Glaisher

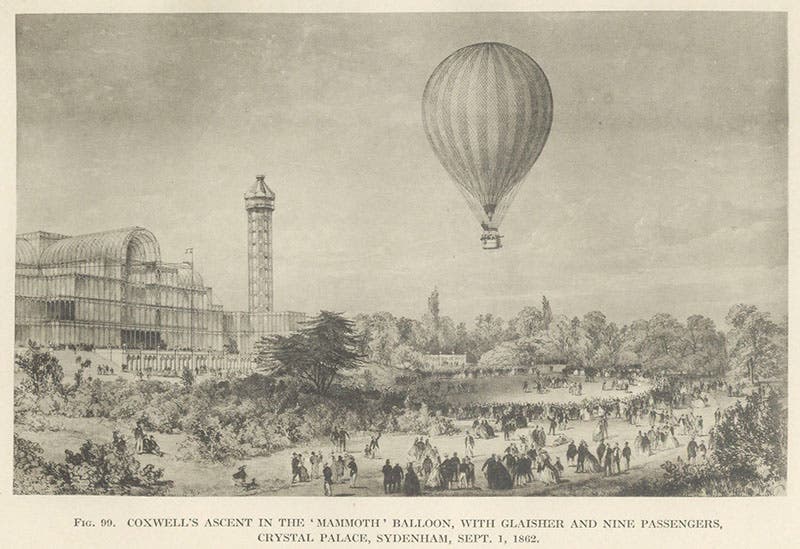

James Glaisher, a British meteorologist and balloonist, was born Apr. 7, 1809. The birth-class of 1809 was a good one, including Charles Darwin, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Abraham Lincoln, Edgar Allen Poe, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Felix Mendelssohn. Glaisher is not as well-known as these six, but he was unexcelled as a scientific balloonist. He spent the first 53 years of his life preparing for, and becoming, an expert on meteorology, working at Greenwich. But in 1862, a committee of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, taxed with coming up with a program to study the upper atmosphere, selected Glaisher to supervise such an effort. They ordered a balloon, called the Mammoth, with which to pursue their high-altitude investigations (third image). That meant hiring a balloonist, and Glaisher chose an experienced one, Henry Coxwell. Glaisher had no intention of leaving the ground himself, but he was talked into taking part in a training flight in 1862, and he was hooked. He was soon an ardent balloonist, partnered always with Coxwell.

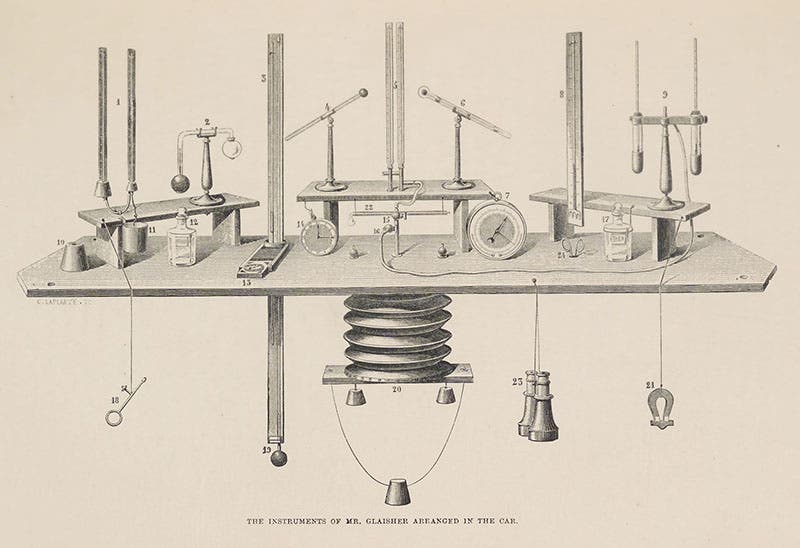

Glaisher designed a "balloon board" that fit across the wicker gondola and sported a variety of barometers (for measuring the altitude), thermometers, hygrometers, and clocks, all carefully fastened down but quickly detachable, lest they needed to be quickly stored in the event of an upcoming hard landing (fourth image). Glaisher became a master of his instrument board, able to take and record an observation every 3 seconds from his array, while Coxwell managed the ups and downs of the balloon. They flew originally from Wolverhampton in the Midlands, where there was a coal gas plant, and a plant manager who was enthusiastic about coal-gas ballooning. They also flew from the Crystal Palace grounds in Sydenham (third image), where their ascents attracted large crowds, and sometimes over London.

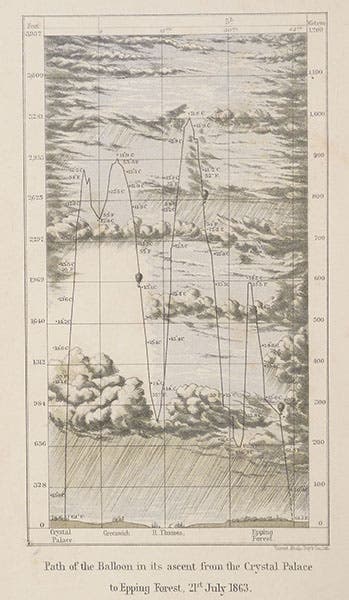

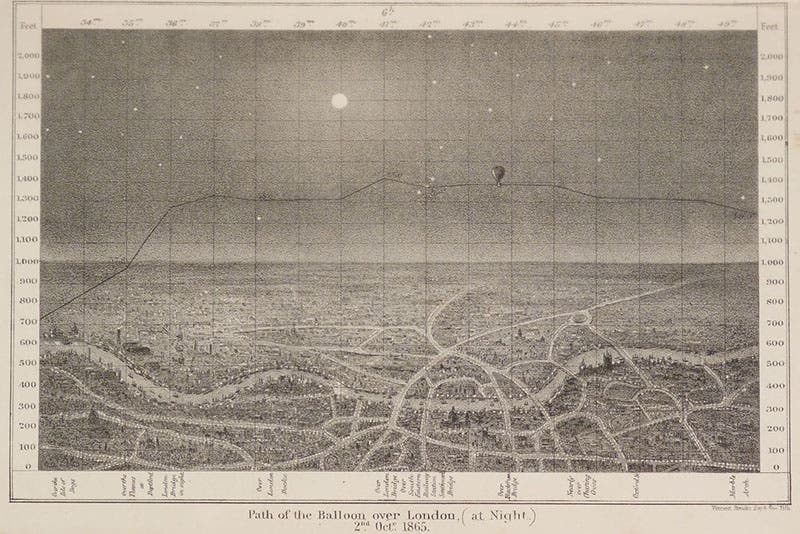

Because he collected so much data, Glaisher was able to devise unique methods of graphic display for his balloon ascents. A typical graph for a complete ascent might display the altitude reached over time, the changing temperature with increase in altitude, and the changing geographic location, and even such variables as the deepening blue of the sky at higher altitudes. We show here two of those graphics, as printed in Glaisher’s Travels in the Air (1871), one of the classics of ballooning literature. The first (fifth image, just below) shows a flight from Crystal Palace on July 21, 1863, that travelled over Greenwich and the Thames and landed in Epping Forest. This flight only ascended to 3300 feet, and the temperature never dropped below 54 °F. Notice the careful depiction of the cloud layers that the Mammoth passed through – Glaisher was first and foremost a meteorologist.

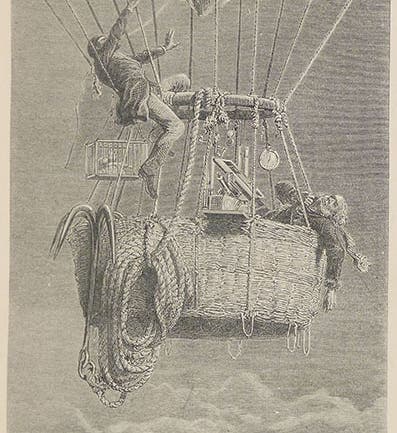

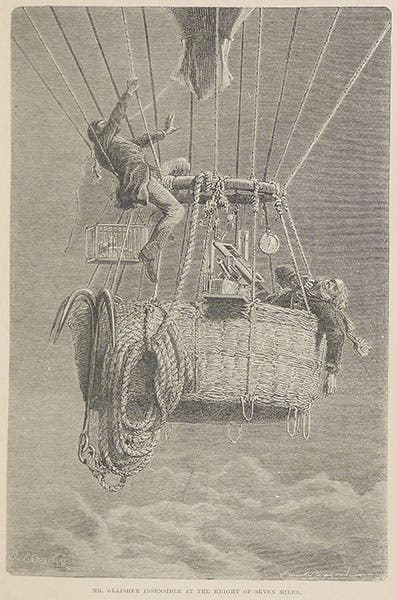

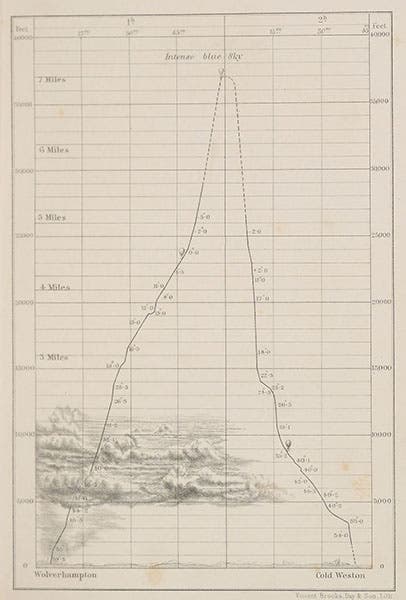

The second such graph we include (sixth image, just above) is sparer but more startling, when you look at the values of the coordinates. This records an ascent of Sep. 5, 1862, from Wolverhampton, that attained, so the graph says, an altitude of 37,000 feet, or about 7 miles! This is a very famous ascent in ballooning history, because Glaisher passed out at 29,000 feet, and the gas-release-valve rope got tangled up; by the time Coxwell freed it, his hands were frozen and useless, so he had to open the valve with his teeth! Both men survived. Clearly Glaisher made no altitude measurements while insensate, so the altitude was estimated by the amount of time that elapsed, and he later modified the estimate to 32,000 feet, which was probably closer to the mark. We told the story, more fully, in our post on Coxwell. The appeal of the tale probably owes a great deal to a wood engraving made by Charles Laplante, showing the gondola of the Mammoth with Glaisher unconscious and the desperate Coxwell trying to open the valve. It appeared not only in Glaisher's book (first image), but in quite a few others, including John Hodgson's magisterial History of Aeronautics in Great Britain (1924). Not surprisingly, it is all over the internet.

Glaisher’s Travels in the Air contains not only an account of his balloon adventures (and all but one of the images shown here), but also narratives on the balloon exploits of Camille Flammarion, Gaston Tissandier, and Wilfrid de Fonvielle, written by the aeronauts and edited by Glaisher, who also commissioned the wood engravings. In our post on Fonvielle, all but one of the images came from Glaisher’s book. It is available online in our Library’s digital collection, as is Hodgson’s well-illustrated History of Aeronautics (1924), online here.

There is an excellent account of the ballooning career of Glaisher in Richard Holmes’ book, Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air (2013), a history of the Age of Ballooning written for a general audience that is very readable and knowledgeable. If scientific ballooning intrigues you, we have also written posts (in addition to the four already mentioned) on Charles Green, Nadar, John Wise, and the ill-fated Sophie Blanchard.

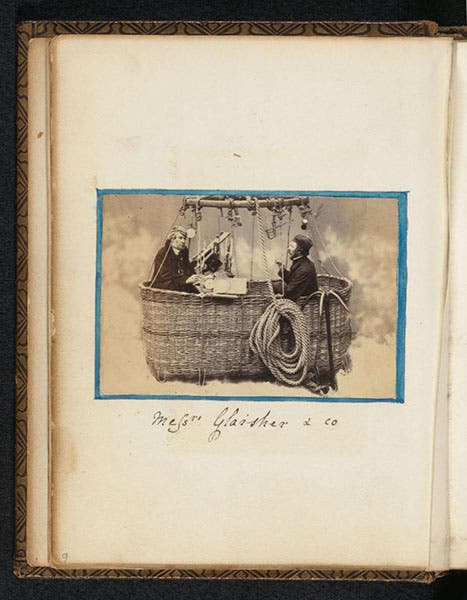

For our final image, we thought we would show you a delightful photograph of Glaisher and Coxwell that is not quite what it seems. It shows the two men in the gondola of the Mammoth (Glaisher on the left), but this is a studio shot, with the gondola firmly on the ground and a backdrop of the sky in place. The photo is unique, part of a photo album held by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.