Scientist of the Day - James Gully

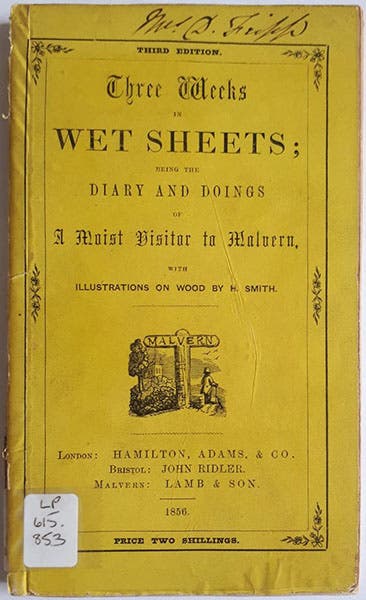

James Gully, an English physician, was born Mar. 14, 1808. In 1842, Dr. Gully, with a partner, set up a hydropathy (hydrotherapy) establishment in Great Malvern, in Worcestershire. More popularly known as a "water-cure," Dr. Gully's spa provided treatments based on his belief that the body could be cleansed of toxins and disease by a bland diet, long walks in the Malvern hills, and an extensive regimen of cold showers, steam baths, wraps of cold wet sheets, and massages. The treatments were administered in Tudor House and Holyrood House, two large and handsome buildings that still survive and indeed prosper in modern-day Malvern (third image). One of the many current Malvern websites has a photograph of a contemporary book (1856) that described hydropathic treatment, with the wonderful title: Three Weeks in Wet Sheets: Being the Diary and Doings of a Moist Visitor to Malvern (fourth image).

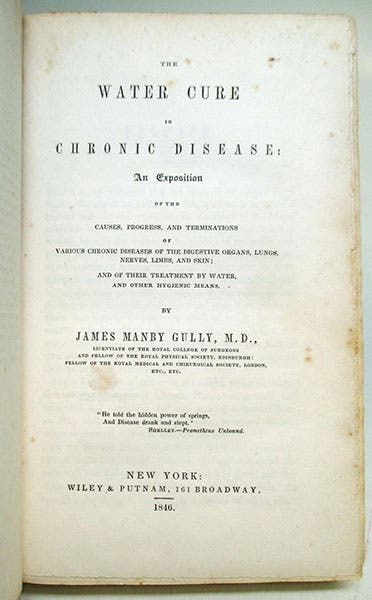

Many famous patients signed up for the "torture," including Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Charles Dickens and his wife. But the most famous patient of all was Charles Darwin, who by 1849 was in wretched health, enfeebled by fatigue and dizziness and wracked by spells of constant vomiting, and ready for a new approach. He read Dr. Gully’s book, The Water Cure in Chronic Disease (second image), secured a few favorable references from former patients, and decided to give it a try. He uprooted his entire family – wife Emma, 6 young children, and assorted maids and attendants – and moved from Down House in Kent to Malvern in Worcestershire to spend 3 months at Dr. Gully's spa in the spring of 1849.

Darwin found Dr. Gully’s establishment quite wonderful. He loved being fussed over, and the long, harsh treatment sessions were to him quite agreeable, since it meant that something was finally being done about his affliction. His nausea was cured (at least for 30 days) and his strength gradually returned. After his return home, he even had facilities for water treatment installed at Down House, the family residence.

Unfortunately, Dr. Gully was unable to do anything when Darwin's ten-year-old daughter, Annie, came down with scarlet fever and perhaps tuberculosis the next year. Annie died at Dr. Gully's in the spring of 1851, and is buried in the Great Malvern cemetery. That certainly must have colored Darwin’s memories of his days with Dr. Gully.

Darwin revisited Dr. Gully’s spa several more times for shorter stays, but without the success of the 1849 visit, and he gradually gave up on hydropathy. But water-cures proved to be very popular with other afflicted souls, and Malvern became quite the spa town, as it still is. Great Malvern is the name given to the historic center, within Malvern itself.

After Dr. Gully retired, he moved to London, which is why, after his death in 1883, he was not buried in the Great Malvern churchyard, but in Kensal Green, where his tombstone is reasonably clean and healthy, perhaps kept in good shape by regular hydrotherapy treatments (fifth image).

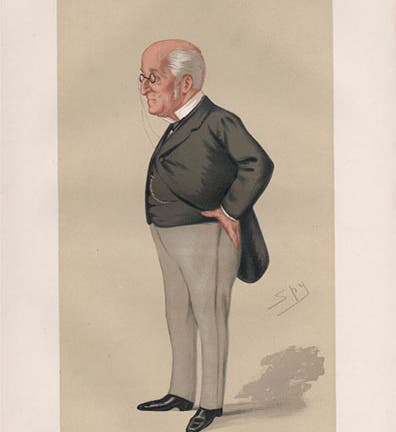

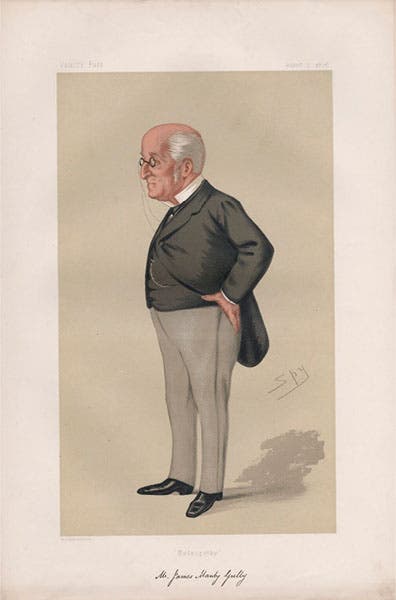

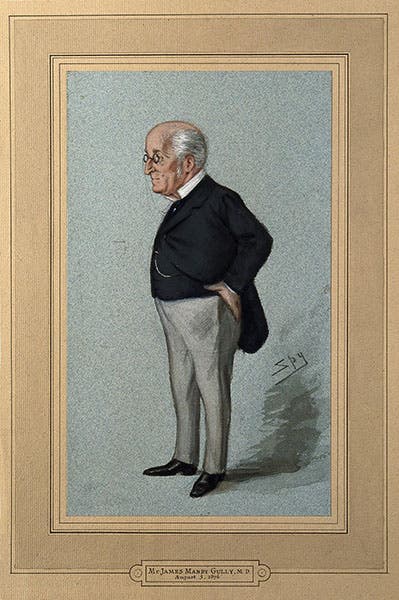

Well before his death, on this day, Aug. 5, in 1876, Dr. Gully was honored with a lithographed caricature in Vanity Fair by “Spy”, the pen signature of Leslie Ward (first image). The print is captioned: “Hydropathy.” We accidentally discovered, in researching this post, that the Wellcome Collection in London has the original watercolor by Leslie Ward from which the Vanity Fair lithograph was made (sixth image). The two portraits, original and print, seem to bookend this piece quite nicely.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.