Scientist of the Day - James Pugh Kirkwood

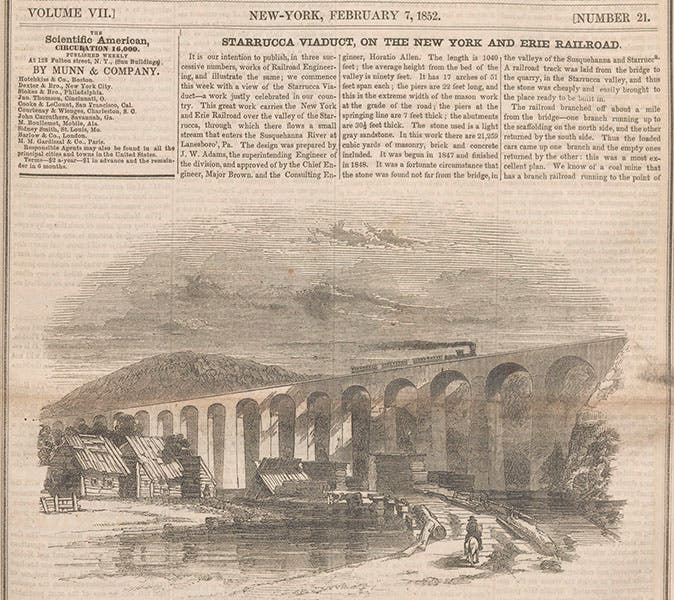

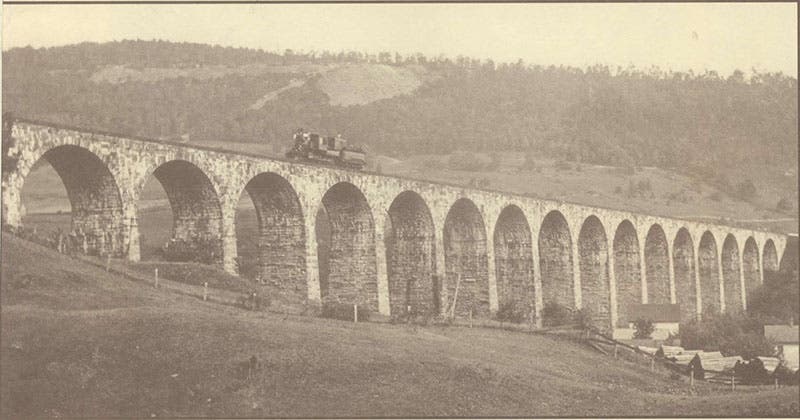

James Pugh Kirkwood, an American civil engineer, died Apr. 22, 1877, at the age of 70. Kirkwood was born in Scotland, but he spent most of his life building railroads in the United States. His most impressive accomplishment was designing and building the Starrucca Viaduct across a valley in Lanesboro, Pennsylvania, near the city of Susquehanna, on the northern border of the state. This was a railroad bridge, built for the New York and Erie Railroad, and it lay on the line connecting New York City and Buffalo. The Starrucca Viaduct was completed in 1848, and it was built entirely of local bluestone. The viaduct has 18 pillars framing 17 arches; each of the arches has a span of 50 feet and is slightly horseshoe shaped, with the pillars thickening gently as they go down. The roadbed clears the creek below by about 116 feet.

The Starrucca Viaduct is a most impressive structure. It can be compared to another famous railway bridge, the Kinzua Viaduct, also built for the Erie Railroad in northern Pennsylvania, but 200 miles further west, and completed 35 years later. The Kinzua Viaduct (designed by Octave Chanute; there is a view of the viaduct at our post on Chanute; here is another) was built of wrought iron (later replaced with steel), and it looks like the more impressive achievement, since it is not clear now those spindly iron legs could hold up the roadway. And it truth, they couldn’t. The rebuilt bridge was levelled by a tornado in 2003, after standing for 121 years. The masonry Starrucca Viaduct has stood for 174 years and still carries railway traffic. If this were a contest, the Starruca Viaduct would be the clear winner.

It should be said that Julius Adams was superintending engineer for the railroad and Kirkwood worked for him, and it is not clear who was chiefly responsible for the design, although it is likely that this was Kirkwood’s achievement. Our four views of the Starrucca Viaduct come from a Scientific American front-page article in 1852 (second image); a photograph taken 53 years later, in 1905 (third image); a modern aerial photograph (fourth image); and a painting by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1865), now in the Toledo Art Museum (first image).

After his stint with the New York and Erie Railroad in Pennsylvania, Kirkwood moved to St. Louis in 1850 to take over the construction of what was then called the Pacific Railroad, the first railway to venture west of the Mississippi. He determined the route and supervised the laying of the first stage of the railway (which would later be called the Missouri Pacific) in 1852. Just west of St. Louis, a town was laid out on either side of the tracks, and it was named Kirkwood, after our engineer. A lovely railroad station was built there, completed after Kirkwood's death, and called the Kirkwood Station. It is considered a fine example of "Richardsonian Romanesque" architecture, and Amtrak trains still stop there, although the station itself is now privately owned and listed on the National Register of Historic Places (fifth image, below).

In 1865, Kirkwood was appointed Chief Engineer of St. Louis, with responsibility for redesigning their waterworks. However, the city fathers were apparently in no mood for innovation, so Kirkwood quit and went back to New York. But he published the results of his survey of waterworks throughout Europe and their suitability for the American Midwest, as Report on the Filtration of River Waters, for the Supply of Cities, as Practised in Europe, Made to the Board of Water Commissioners of the City of St. Louis (1869). Not only do we have this book in our collections, we have Kirkwood’s personal copy, with his book stamp, and numerous pencil annotations throughout. It came to us when we acquired the Engineering Societies Library in 1995.

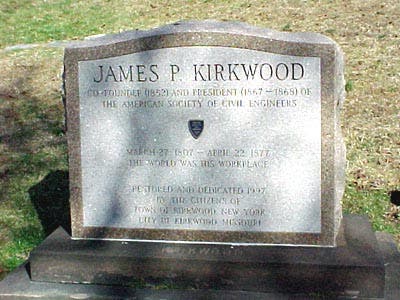

Kirkwood died in 1877 and was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. As his tombstone tells us (sixth image), in addition to the achievements discussed above, he co-founded of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) in 1852, and was the second president of the ASCE in 1867. If you visit his grave, look around for the nearby graves of Samuel F.B. Morse, Peter Cooper, Nathaniel Currier, Elias Howe, and Ormsby MacKnight Mitchell, to name just a few of the scientific luminaries interred at Green-Wood.

There is only one portrait of Kirkwood, an unfortunate photograph that I would not like to have as my sole surviving visual memento. Therefore, I do not show it here. But you may take a look for yourself at the ASCE website.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.