Scientist of the Day - James Sowerby

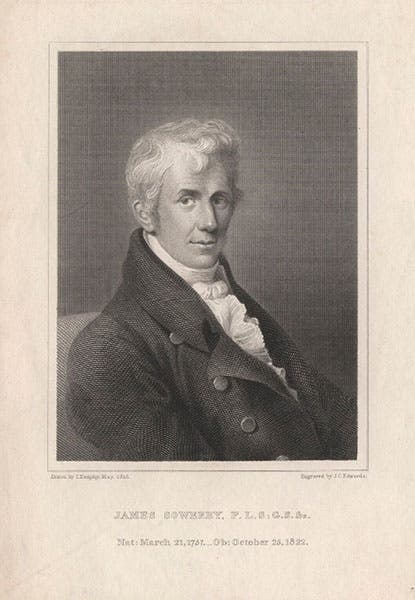

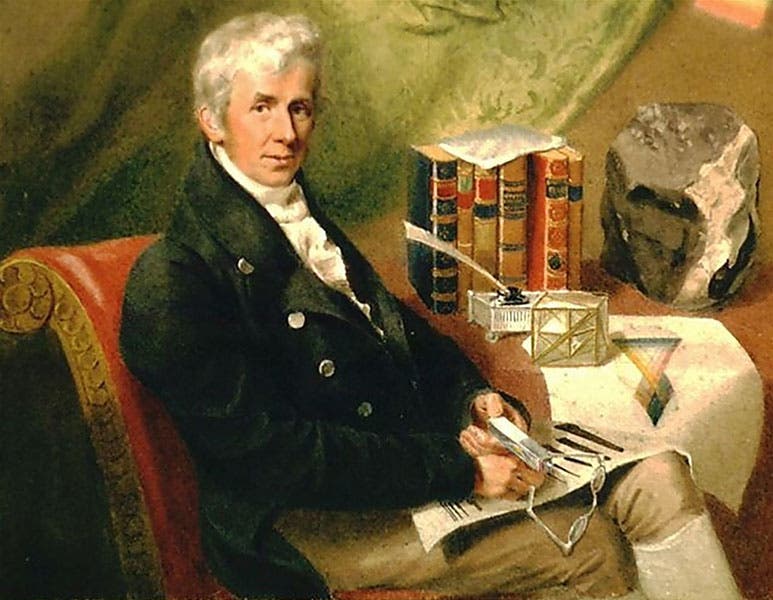

James Sowerby, an English artist, collector, and engraver, died Oct. 25, 1822, at age 65. Sowerby was a Royal-Academy-trained painter who loved flowers, and he found that he was able to support himself and his family by drawing, engraving, and publishing plant illustrations for public consumption. Sowerby published English Botany in 36 volumes over the course of 14 years (1790-1814), with several thousand hand-colored engravings. We have, I am slightly embarrassed to say, two complete sets of this beautiful work in the History of Science collection. We would probably happily trade one for a set of Sowerby's British Mineralogy (1804-17), which we do not have, or perhaps his Mineral Conchology of Great Britain (1812-[46]), but no one has made us any offers. Sowerby had three sons – James De Carle, George, and Charles – and all were trained by James to be artists and engravers. He must have been an exceptional teacher, for all three proved to be the equal of their father. George, for example, engraved the plates for Charles Darwin's volumes on barnacles (1851-54).

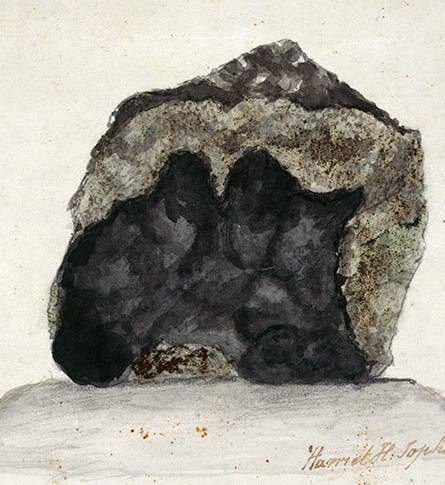

The most frequently reproduced portrait of Sowerby père shows him in a reading chair with a large and unusual rock-like object on the table beside him (third image). That is the Wold Cottage meteorite. This 56-pound chunk of stony iron fell in the hamlet of Wold Newton in Yorkshire on Dec. 13, 1795, on the property of one Edward Topham, and was sketched by his daughter (first image). Topham tried to turn it into a tourist attraction, even erecting a monument on the impact site (which still stands), but it must not have been a successful venture, for in 1804, he sold the meteorite to Sowerby, who displayed it in a museum in his home, and engraved its image for the second volume of his British Mineralogy (which, as I have lamented, we do not own).

In 1806, Sowerby acquired another meteorite, a large piece of the Cape of Good Hope meteorite that fell sometime around 1793 in South Africa (its fall was not observed, or at least not recorded). Sowerby had it tested by two chemists to confirm its other-worldly origin (chemists had just learned how to do that; see our posts on Smithson Tennant and Edward C. Howard). After that, the meteorite apparently just sat there in the shadow of the Wold Cottage meteorite until Emperor Alexander I of Russia arrived in London in June of 1814. Alexander was fresh from a successful invasion of Paris that forced Napoleon into exile at Elba, and was now on a triumphal tour, which included a stop in London. It occurred to Sowerby that a sword made from meteoritic iron would indeed be a “heavenly blade” for a conquering hero, and he immediately grabbed his Cape of Good Hope fragment and went scurrying for a swordsmith. He thought that such a sword, presented to Alexander while in London, would bring glory to Alexander, London, and perhaps James Sowerby.

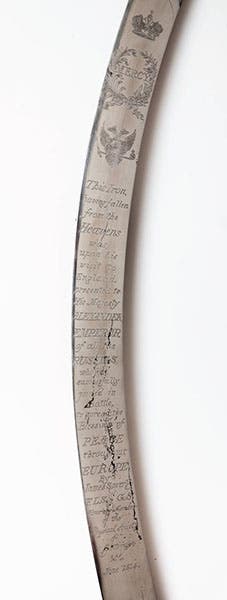

The sword was wrought in a matter of days and fitted into a custom-made mahogany case; It was the first sword ever made from a meteorite (fourth image). Sowerby then sought an occasion for presenting it to Alexander. But because of the intricacies of diplomatic channels, he never got the chance. The Emperor left London unaware of the existence of his custom-made sword. So Sowerby was forced to ship his gift to Russia in a diplomatic pouch, accompanied by a letter explaining the unusual nature of the weapon.

In the opinion of some of the members of Sowerby’s social circle, Alexander did not deserve the sword, and this view would seem to be borne out by subsequent events. Sowerby received no acknowledgement from Alexander or anyone else in Russia, and for the next four years, he tried in vain to find out if the Emperor had even received it. Finally, in 1819, he received a note of thanks, written on behalf of Alexander, and an emerald and diamond ring as a return present. But the sword had seemingly disappeared, and it was not heard of again until 2005, when a scholar found it in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. The mahogany case had disappeared, but the sword and scabbard seemed to be in good shape (fourth image). We can now read the inscription etched into the blade (fifth image): “This Iron, having fallen from the heavens was, upon his visit to England, presented to his Majesty ALEXANDER, EMPEROR of all the RUSSIAS, who has successfully joined in battle, to spread the Blessings of PEACE throughout EUROPE. By James Sowerby F.L.S. G.S. Honorary Member of the Physical Society of Göttingen &c June 1814.”

Given the lack of gratitude of the Emperor, it seems a pity that Sowerby did not choose to honor King Karl XIII of Sweden instead. Then Sowerby might have fashioned his piece of celestial iron into Mjölnir, the hammer of Thor. That would have been a much more fitting transmutation for a thunderstone such as the Cape of Good Hope meteorite.

We drew much of our information concerning Alexander's sword, and three of the images reproduced here, from an excellent article by Paul Henderson in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London in 2013. We are also grateful to the Royal Society for choosing this week as their annual Open Access week, which means you have until Oct. 29 to read the article for yourself for free, if you so choose. You may find it here.

The Wold Cottage meteorite was sold to what is now the Natural History Museum in London in 1835 by his family after Sowerby’s death; we show you (sixth image) the photo on the Museum’s website. You’d think there would be a better image available somewhere online, showing the meteorite actually on display, but I could not find one. However, the Wold Cottage meteorite is better off than the Cape of Good Hope meteorite, of which nothing seems to have survived in public collections except for the sword of Alexander, which apparently still resides somewhere in the archives of the Hermitage Museum, but not on display.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.