Scientist of the Day - James Walker

James Walker, a Scottish civil engineer, was born Sep. 14, 1781. Walker was involved in all sorts of engineering projects, designing railways, docks, bridges, canals, and, most prolifically, lighthouses. Walker is seldom mentioned in the same sentence with lighthouse engineers such as John Smeaton, Robert Stevenson. and James Douglass, but he should be.

Walker built his first lighthouse in 1821 (the West Usk lighthouse), and he soon became chief consulting engineer to Trinity House, the corporation that oversees all the lighthouses in England. Over the next 30 years, he designed and supervised construction of more than 20 lighthouses, including the Trwyn Du Lighthouse at the eastern extremity of Anglesey (first image); Smalls Lighthouse off the coast of Wales (second image) and the dramatic Needles Lighthouse at the end of the formation that tapers out from the Isle of Wight (third image). The heli-pads on the top of two of these were much later additions, made necessary by the difficulty of accessing these structures. You can imagine what it was like to build them in the first place.

Walker’s toughest assignment was to put a lighthouse on Bishop Rock, the westernmost isle of the Isles of Scilly, which lie off the coast of Cornwall. It is a bit of an overstatement to call Bishop Rock an isle – even islet is overly generous, since it is nothing but a small chunk of igneous rock that sticks up out of the ocean. Walker didn’t think that a stone lighthouse, like the Eddystone Light, could withstand the high winds and the battering of the waves, so he first erected a structure on iron legs embedded in the rock. Work began in 1847 and was almost completed, but before they could put the lighthouse in operation, it was torn away by a gale in 1850.

Walker was undeterred and started over, this time reverting to the idea of a stone structure like Eddystone. Granite blocks were dressed on the mainland, shipped to the site, and laid in place, each one dovetailed to the others as at Eddystone. Initial work was slow because part of the rock was underwater even at low tide, and so a cofferdam had to be built for the first few blocks. Even above water, work was slow, and it took seven years to complete the structure. The finished lighthouse, opened for business in 1858, was 115 feet tall and weighed some 2,500 tons, about as much as ten large Egyptian obelisks. The lighthouse is still there, but you cannot see it from the outside, because between 1881 and 1887, James Douglass enclosed it in a thick granite sheath that extended the height to 155 feet.

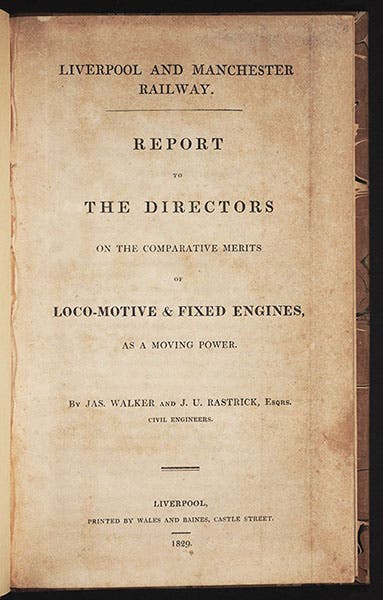

The only piece of Walkeriana that we have in the Library has nothing to do with lighthouses. In 1829, Walker was asked by the officers of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway to study whether stationary engines or locomotives would be more suitable for their soon-to-be-opened line. Walker responded with a printed report: Liverpool and Manchester Railway: Report to the directors on the comparative merits of loco-motive & fixed engines, as a moving power (1829). It is one of the scarcer pieces of railroad incunabula; we acquired our copy in 2008 from New York bookseller Jonathan Hill.

A memorial bust of Walker can be seen on Greenland Dock in London.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.