Scientist of the Day - Jane Colden

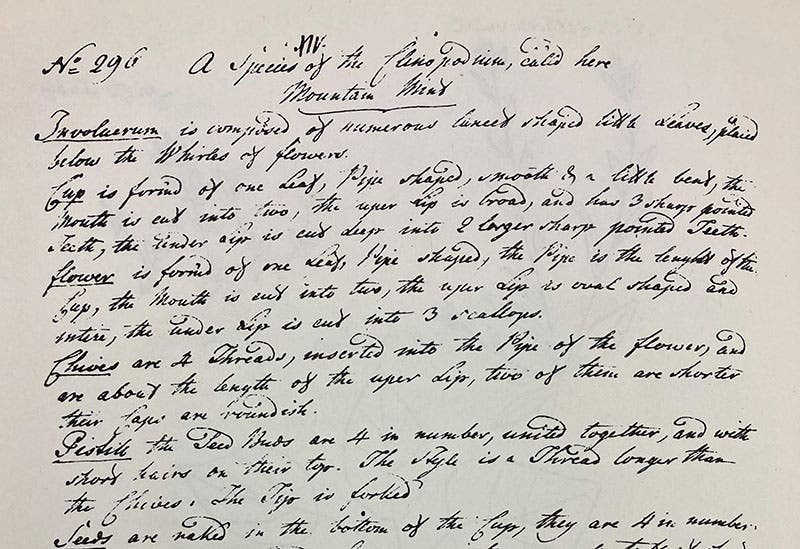

Jane Colden, a colonial American botanist, was born Mar. 27, 1724. She was the daughter of Cadwallader Colden, an Edinburgh-trained physician and a prominent figure in the Colony of New York which he served as Surveyor-General and later as Lieutenant-Governor. Cadwallader acquired an estate of three thousand acres in Orange County near the Hudson River, between Albany and New York City, where Jane grew up, and where she developed a fascination for plants and flowers. Cadwallader must have taught Jane, who was his precocious fifth child (of ten), the basics of Linnaean botany, for it was brand new in the 1750s. Carl Linnaeus had published his Genera plantarum in 1737, and his Species plantarum in 1753, and in these two works, he divided the plant kingdom into 24 classes based on the structure of the male flower, and then broke each class down into orders based on the structure of the female flowers. It was therefore a sexual system of classification, and later in the century would be quite controversial. But in the 1750s, it was simply new, and very attractive to a botanist like Jane, because it was so easy to use – count the pistils and stamens, and there you were. Jane took to it immediately and compiled a manuscript describing 340 species of plants that she herself collected in New York along the Hudson River, with each description accompanied by a line drawing. Her descriptions are thorough, accurate, and suggest to modern botanists that she had an exceptionally keen eye and great patience. Each of the plants in her manuscript is described according to the Linnean system, a first for any botanist in colonial America, male or female.

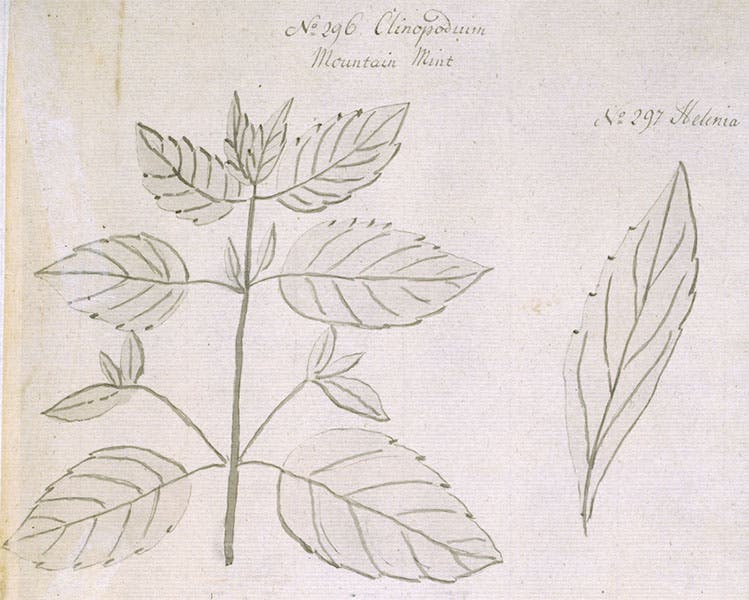

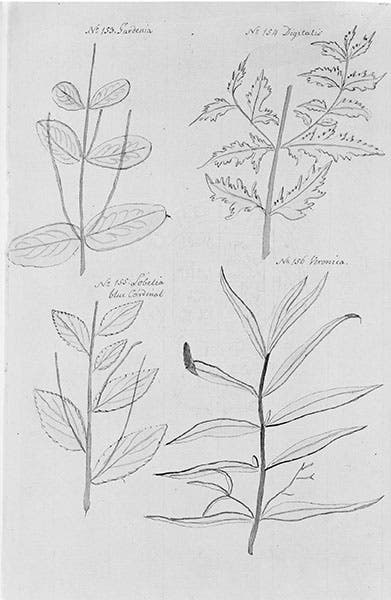

Jane's botanical skills came to the attention of John Collinson, the Quaker merchant and gardener in London whom we discussed in our post on John Bartram just a few days ago. Bartram himself spoke highly of Jane's work, and another botanist mentioned Colden to Linnaeus, although Linnaeus's own opinion of Colden is not known. Jane knew Alexander Garden of South Carolina, who like Bartram supplied seeds and plants to London collectors, and she tried to name a plant after Garden (first image), but it turned out that Gardenia was already taken as a name, so that her Gardenia is now our Hypericum, or St. John's wort.

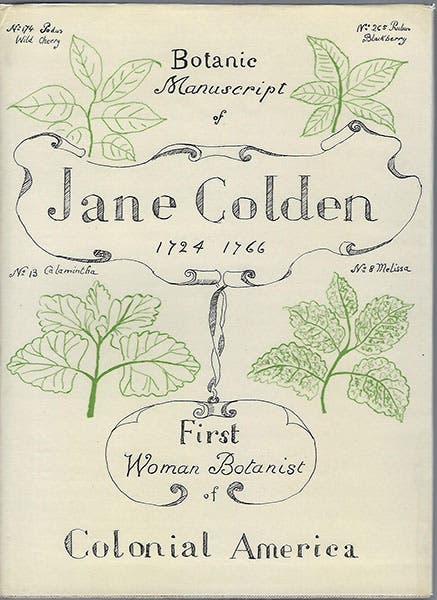

I don't think any attempt was made during Jane's lifetime to publish her manuscript. She married in 1759 and seems to have given up her botanical pursuits upon becoming Mrs. Farquhar. And then she died, too young, in 1766, just shy of her 42nd birthday. The manuscript passed through several hands, beginning with those of a Hessian mercenary, and finally ended up in the considerable library of Joseph Banks in London. All of Banks’ collections and books then went to the British Museum, including Jane Colden's botanic manuscript. It originally had no title page, but one of the German owners provided one that we now usually ignore. The manuscript is currently in the Botany Library of the Natural History Museum. Strangely, neither the library nor the Museum has made much effort to make it more widely available. They did allow the curator of the New York Botanical Garden Library to reproduce the ink drawings in black-and-white and fifty or so of the hand-written descriptions, along with transcriptions, and publish them as Botanic Manuscript of Jane Colden, 1724-1766, under the auspices of the Garden Club of Orange and Dutchess Counties, New York. We have this work in our collection, and we show a detail of one of the descriptions in our copy (second image), but we lack the stylish dust jacket, with four of Colden's drawings reproduced in green ink, so we show that from a copy currently being offered for sale (fourth image). However, the Natural History Museum has not made any of the drawings or the hand-written descriptions available online – at least, I could find any. The only two I could turn up were in an article in the online version of Atlas Obscura, which I include here (first and third images).

If you search Google Image for a portrait of Jane Colden, you will turn up many thumbnails, but none of them are valid – they show other Colden women, or other women on websites where Jane is mentioned, but not Jane herself. An enterprising blogger compiled a composite of four Colden women whose portraits are often confused with that of Jane, and I show it here (fifth image). Jane’s mother Alice is at top left, her sister Elizabeth is at bottom left, and the other two are Jane’s nieces. None of them is Jane. It is not improbable that a portrait of Jane will show up one day, perhaps a miniature that has been misidentified. You can see a larger black-and-white version of the portrait of Jane’s mother, “Mrs. Cadwallader Colden” (as she is labelled) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which also has the corresponding portrait of Jane’s father, this time reproduced on the museum website in color.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.