Scientist of the Day - Jean de Charpentier

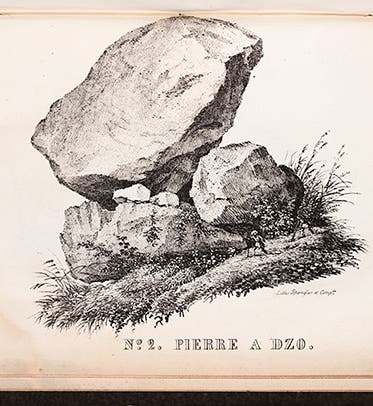

Jean de Charpentier, a German-Swiss geologist, was born Dec. 7, 1786. Charpentier was one of the first proponents of the idea that the glaciers of the Alps had once extended far beyond their present environs. His evidence lay in "erratics", as they were called – huge boulders that dot the lower Alpine landscape, and are completely foreign to the terrain upon which they sit. A number of these cluster around the town of Monthey, on the lower Rhône, just above Lake Geneva, and not too far from Charpentier's home base of Bex. One impressive specimen is the "Pierre a Dzo" (first image), which is actually two erratics, one perched delicately on the other. It was hard to imagine what kind of force could move two such mammoth rocks from their place of origin, which Charpentier traced to a spot some 20 miles up the valley, and leave them in such a position.

To Charpentier, a flood was inadequate, as was a floating iceberg; the only possible explanation was that the glaciers of the Alps had once extended down the Rhône valley all the way to Lake Geneva and had carried the erratics down with them, and then left them behind when the glacier receded. Charpentier conveyed his ideas to Louis Agassiz, who transformed them into the idea of an Ice Age, and who today receives most of the accolades for a discovery that was only partly his own.

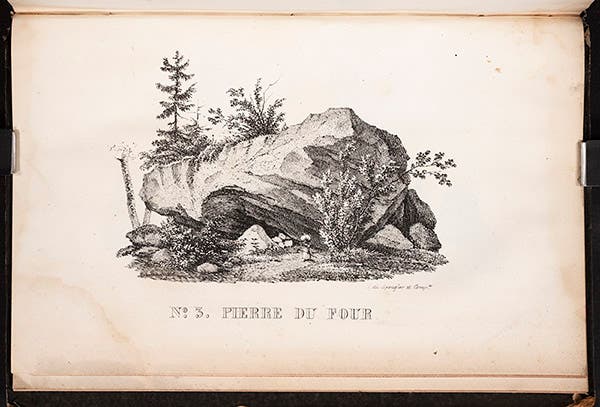

Charpentier published his ideas on erratics in his Essai sur les glaciers et sur le terrain erratique du bassin du Rhône (1841), where he displayed seven erratics, including lithographs of not only the Pierre a Dzo, but the Pierre du Four (second image) and the Pierre des Marmettes (third image). We displayed this book in our 2008 exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance, where it was opened to the lithograph of the Pierre des Marmettes.

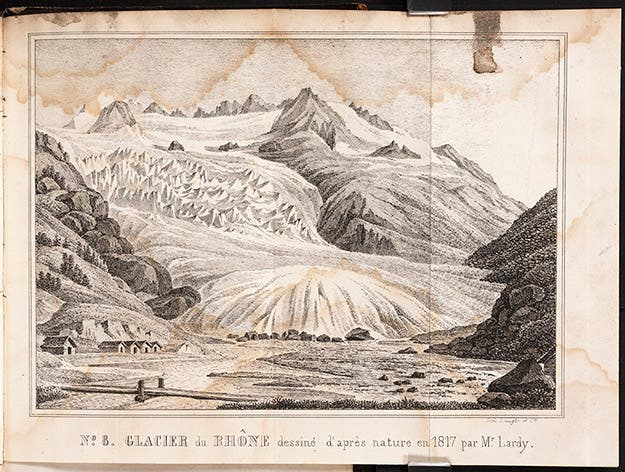

At the very end of the plate section at the back of the book, Charpentier included a drawing of the present appearance of the Rhône glacier, now far up the valley (fourth image). Our plate is quite water-stained, as you can see. But this often happens to books in their extended lifetimes; long before it came to rest here, this book was set at some point in a small puddle of water and the liquid seeped around the back cover and into the last plate. It is nothing to be ashamed about, and we have no qualms about displaying it in its picturesquely damaged condition.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.