Scientist of the Day - Jean-François d’Aubuisson de Voisins

Jean François d'Aubuisson de Voisins, a French geologist and mining engineer, was born Apr. 19, 1769, the same annus mirabilis that produced Georges Cuvier, Alexander von Humboldt, Marc Isambard Brunel, and Napoleon Bonaparte. D’Aubuisson was born into a well-to-do family in Toulouse and spent 6 years in the army in Spain before deciding to enroll in the famous mining academy at Freiberg in Saxony, presided over by Abraham Gottlob Werner. Werner was a neptunist, meaning that he thought all rocks are sedimentary in origin, deposited as strata from water, and he dismissed the arguments of vulcanists, such as Nicolas Desmarest, who thought that many kinds of rock, such as basalt and granite, had cooled from a molten state.

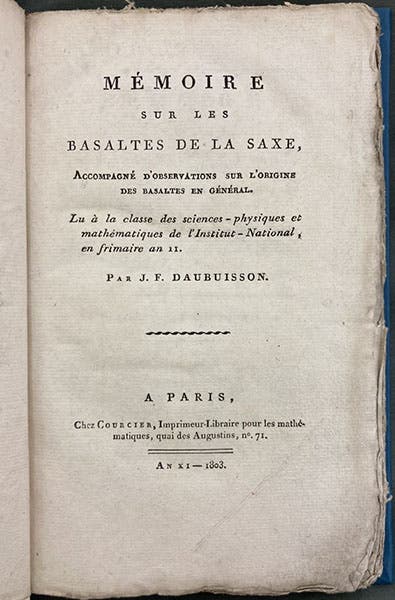

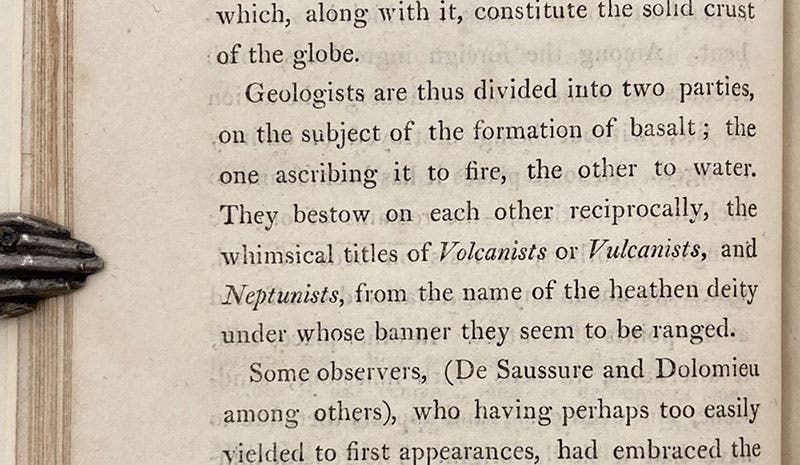

D’Aubuisson initially followed Werner in his geological beliefs, and he published a small book in 1803, The Basalts de la Saxe (The Basalts of Saxony), in which he maintained the sedimentary origin of basalt (third image). Eleven years later, in 1814, his book was translated into English (fourth image). Werner had many followers in England and Scotland, and there was even a Wernerian Natural History Society in Edinburgh, and so they welcomed an English defense of neptunism. In his original preface, d’Aubuisson had explained the difference between vulcanists and neptunists; we show you that passage from the translation (fifth image). The translator did not mention that right after d’Aubuisson published his book, he visited the Auvergne region of France, where there is a lot of basalt about, nestled among the extinct volcanoes, and his faith in neptunism, at least with respect to basalt, quickly eroded away. In England in 1814, he was still welcomed as a neptunist.

D'Aubuisson then entered the ranks of mining engineers, even though he had never attended the École des Mines, and he spent the rest of his life as a chief mining engineer in Tououse. In 1819, he published a general book on geology, called Traité de géognosie, which was quite influential, and was soon enlarged into a 3-volume second edition (1828-35). Geognosy was a bit of Wernerian word-smithing; Werner preferred it to geology, because geologists like to speculate on such things as the origin of the earth, while true geognosts just present the facts, based solely on observations (the irony, of course, is that Werner himself was the arch-theorist of them all). We have both editions of d’Aubuisson’s Traité in our library (the first in its original paper wrappers, sixth image). We displayed the first edition in an exhibition, Theories of the Earth: The History of a Genre, in 1984, as an example of a geology book without a “theory of the earth”. This was the first exhibition, and the first exhibition catalog, that I curated for the Library, in collaboration with Bruce Bradley; it is hard to believe that was 40 years ago. The catalog is available as a PDF here; d’Aubuisson’s Traité (1819) was exhibit item 51.

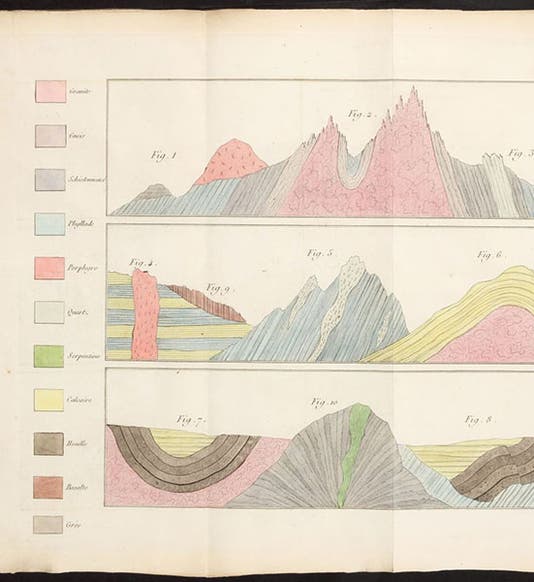

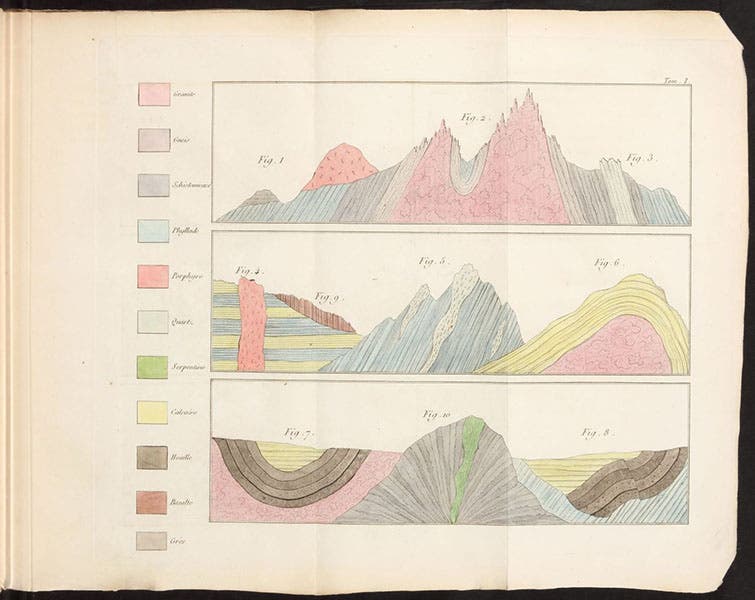

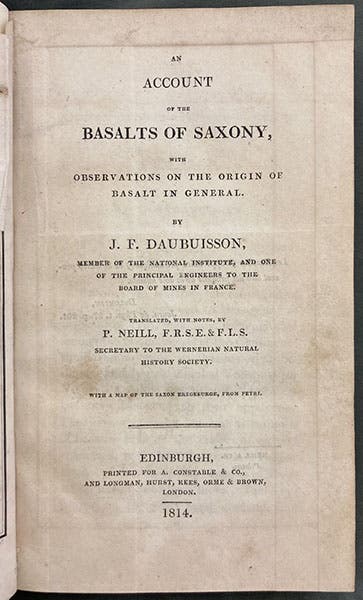

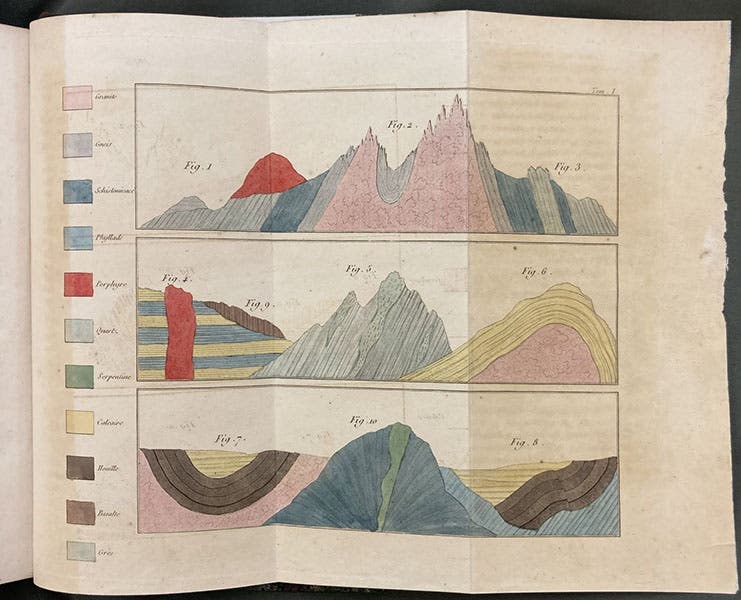

One of the interesting features of the two editions of Traité de géognosie is that one (and only one) plate appears in both editions, a hand-colored engraving with 10 figures showing different arrangements of geological strata. We reproduce both of them here (first image, seventh image), so you can see that, when it comes to hand-colored plates, individual prints tend to differ considerably.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.