Scientist of the Day - Jean Jallabert

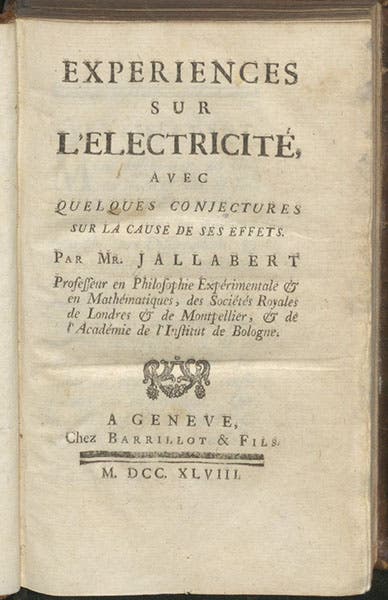

Jean Jallabert, a Swiss mathematician and experimental physicist, was born July 26, 1712. Jallabert started out as a Protestant cleric, but he switched to physics arouind 1744. His particular interest was electricity, which was a hot topic around this time, especially after the Leyden jar was invented. Jallabert made a scientific grand tour, visiting, among others, the abbé Nollet in Paris, and Petrus von Musschenbroek in Leiden, both of whom were prominent electrical investigators. He returned home to Geneva to conduct his own researches, and he published a book, Experiences sur l'electricité, in 1748, which we have in our collections. Four of the images reproduced here were taken from this book.

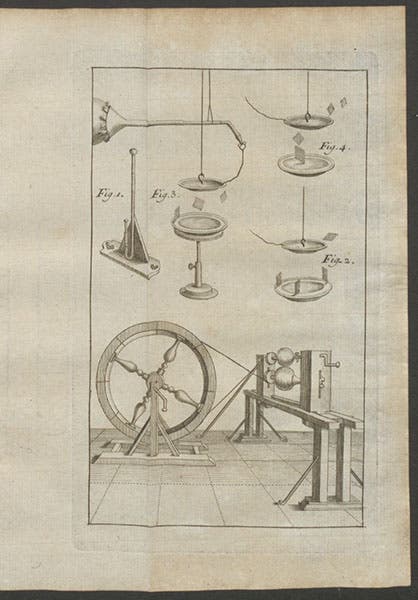

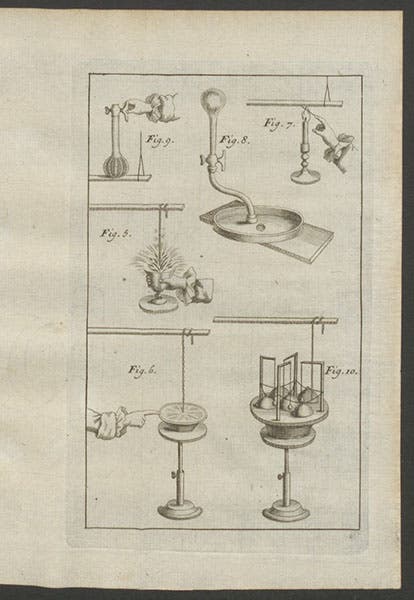

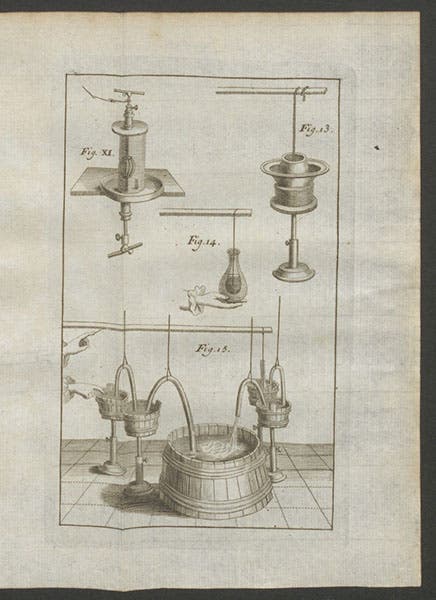

As you can see from the plates, Jallabert did all the usual electrical experiments. He built (or possibly acquired) an electrostatic generator (second image), fitted it with a prime conductor (a metal rod connected to an electrical machine which one could come near or touch to investigate electrical effects, third image), and he even had Leyden jars with which to experiment (fourth image, below). However, if you read later works that attempt to provide a history of electrical experimentation, such as Joseph Priestley's The History and Present State of Electricity (1767), you will find that Jallabert is typically mentioned in a single sentence, and for one solitary discovery: the "power of points." Jallabert found that if you approach an electrified object with a pointed conductor, it will bleed off the electrical charge, usually without a spark, from a much greater distance than a blunt conductor, which usually does provoke a spark. This was an important discovery, because Benjamin Franklin, the next year (1749) went from the power of points to the idea of a lightning rod, which might bleed dangerous electricity out of clouds, if atmospheric electricity did turn out to be the cause of lightning. It is said, by several historians, that Franklin knew of Jallabert's discovery. I have not verified this, but since Franklin knew Nollet, and Nollet knew Jallabert, it is not unlilkely.

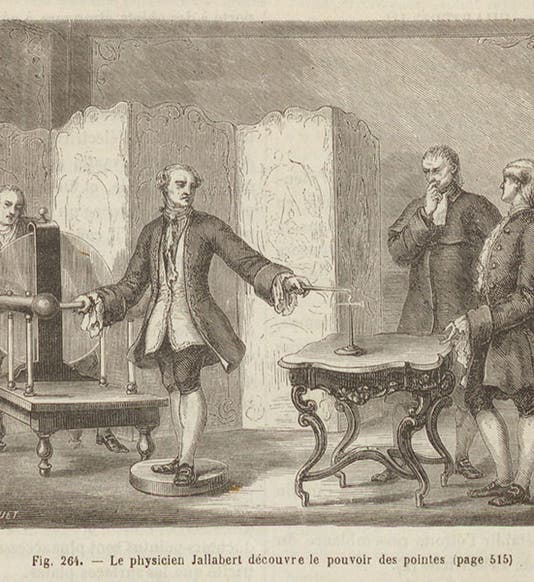

It might be that one of the figures on the plates in Jallabert’s book is intended to illustrate the power of points – it is hard to say. The best illustration of this effect comes from volume 1 of Louis Figuier's Les merveilles de la science (1867-91), a book that we have drawn on many times in these posts. We use his wood engraving, of Jallabert standing on a wax insulator and extending a pointed rod to an object, as our opening image.

The experimental study of electricity goes back to William Gilbert (1600) and Otto von Guericke (1650s), with further advances by Francis Hauksbee (1719), Stephen Gray (1729), and Charles du Fay (1733-37). But the decade of the 1740s showed an astounding increase in the number and variety of publications on experimental electricity, as everyone was grasping for a theory of electricity. We have in our library an impressive collection of such books and papers, all written in the 1740s, by such experimenters as Christian Hausen (1743), Johann Winkler (1744), Ewald von Kleist (1745), Georg Bose (1745), and William Watson (1745-48), as well as Franklin, Nollet, and Musschenbroek. The ones highlighted have been the subjects of posts in our Scientist of the Day series. If you would like a mini-introduction to electrical incunabula, as I like to call electrical publications written in the 1740s, here is your chance.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.