Scientist of the Day - Joan Blaeu

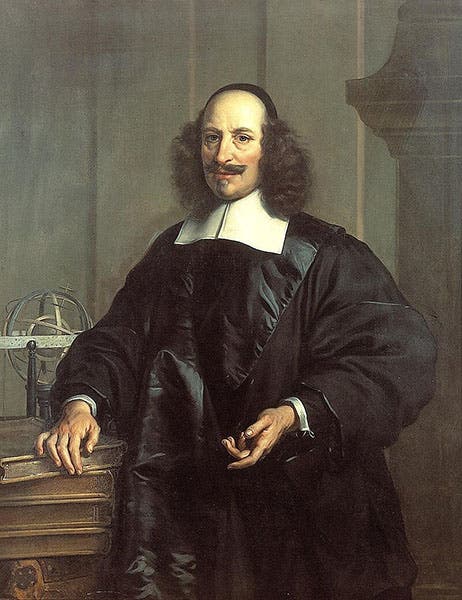

Joan Blaeu, a Dutch printer and cartographer, was born Sep. 23, 1596. Blaeu was the son of Willem Blaeu, who around 1600 began a map- and globe-printing firm in Amsterdam. Joan trained as a lawyer, but instead of practicing law, he joined his father's printing firm, and inherited the business when Willem died in 1638.

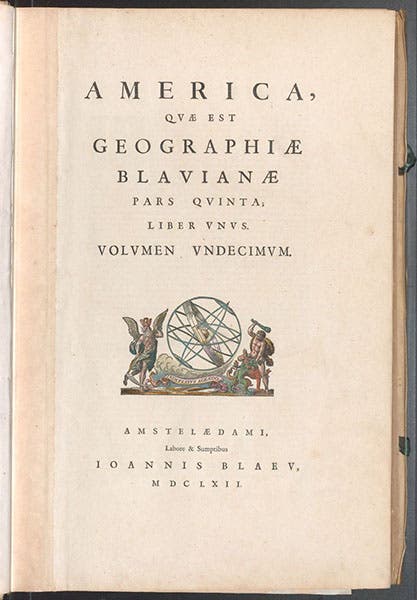

The Atlas, as a collection of uniform maps, had been invented by Abraham Ortelius in 1570, but it didn't change much as a format for 60 years. Then, in the 1630's, the Blaeus and another Dutch cartographic printer, Jan Jansson, began to compete for supremacy in the atlas market, resulting in large, multi-volume sets with, initially, scores of maps, and then hundreds. The culmination of the competition was Joan Blaeu's Atlas maior, published in Latin in 11 large folio volumes in 1662. Our set contains 596 hand colored engravings, most of them double-page maps, in original full-vellum bindings. From a printing point of view, it is the finest atlas ever published.

I wrote a post on Blaeu 9 years ago, and, daunted by the prospect of trying to convey the impact of such large maps on a small screen, I chose instead to focus on the cosmological diagrams in the introduction to volume one, which were generally unknown to historians of early modern cosmology. That was a clever ploy, but it certainly did not capture the essence of Blaeu's Atlas maior.

So we tackle the Atlas again today. We have only scanned two of the 11 volumes – volume 1, with the cosmological diagrams and engravings of Tycho Brahe's observatory at Uraniborg, which we used in a post on Brahe, and volume 11, on the Americas. Today we show some of the maps and engravings from that final volume.

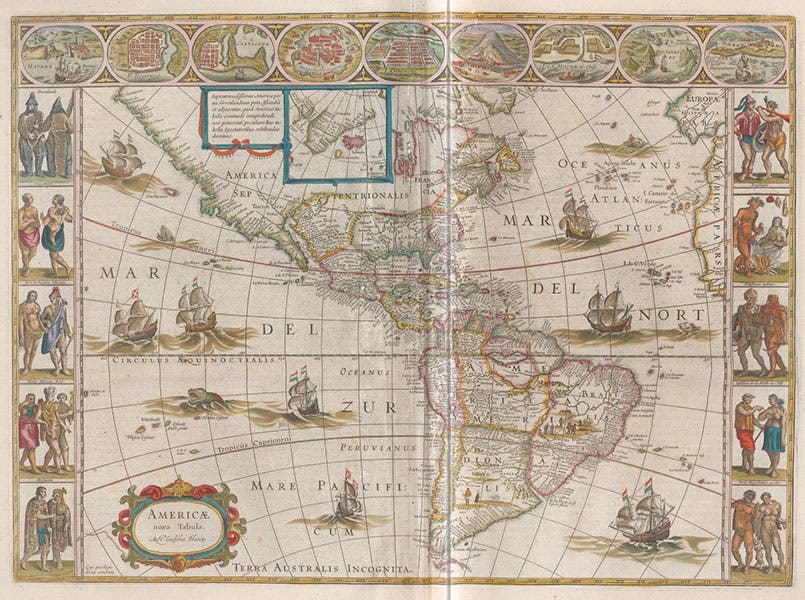

The most compelling map from vol. 11 is surely the first, which shows North and South America together (fourth image). If you compare it to the corresponding map in the Atlas of Ortelius (the second map in our post on Ortelius), you will see that both continents are recognizable in both maps, but the contours of South America have yet to be worked out, and North America, except for the east coast, is still pretty much terra incognita.

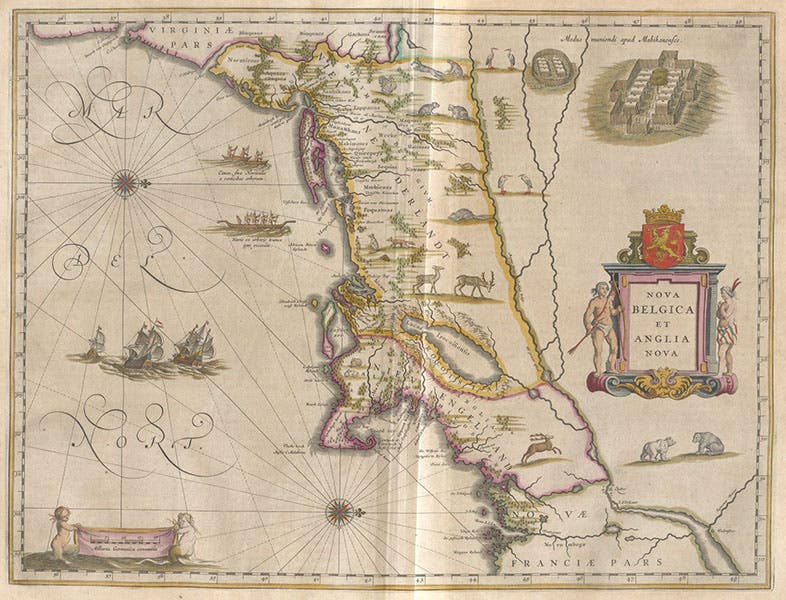

But I find some of the regional maps to be more interesting, probably because, except for Brazil, few areas had really been properly mapped. For North America, Blaeu included maps of New England, Virginia, and Florida. We show the one for New England (fifth image). You will notice that north is to the right, rather than "up", and the same is true for all of the regions on the Atlantic coast. You should be able to spot Cape Cod, and New York City harbor at far left.

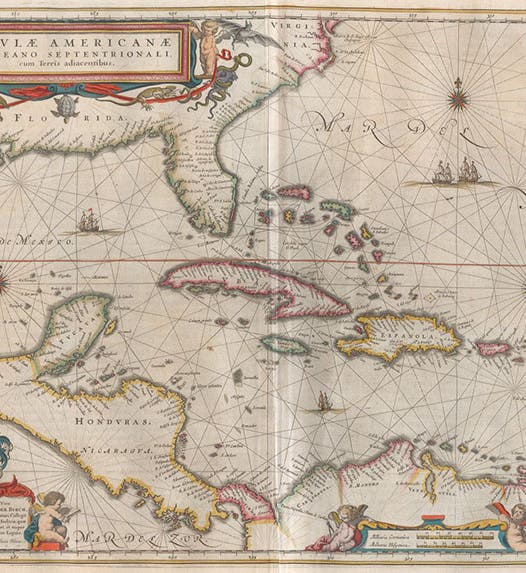

It is not surprising that areas surrounded by the sea are the most accurately mapped. The map of the Caribbean (first image) is immediately recognizable, with reasonably accurate depictions of Cuba and the rest of the Greater Antilles, as well as the lesser Antilles, and he Bahamas.

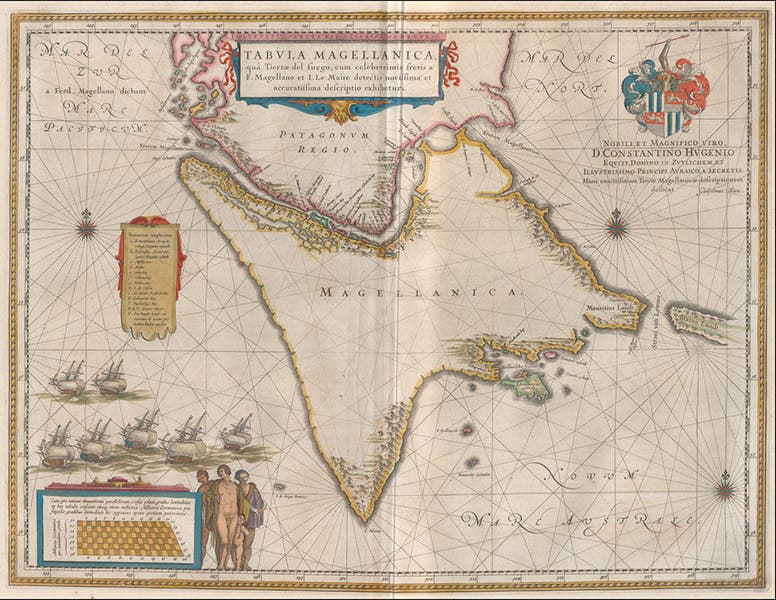

The map showing "Magellanica" is also intriguing, since it shows clearly the Straits of Magellan, which by the time of Blaeu's map had been known for 140 years (sixth image). Patagonia is just above the Straits, and Tierra del Fuego below.

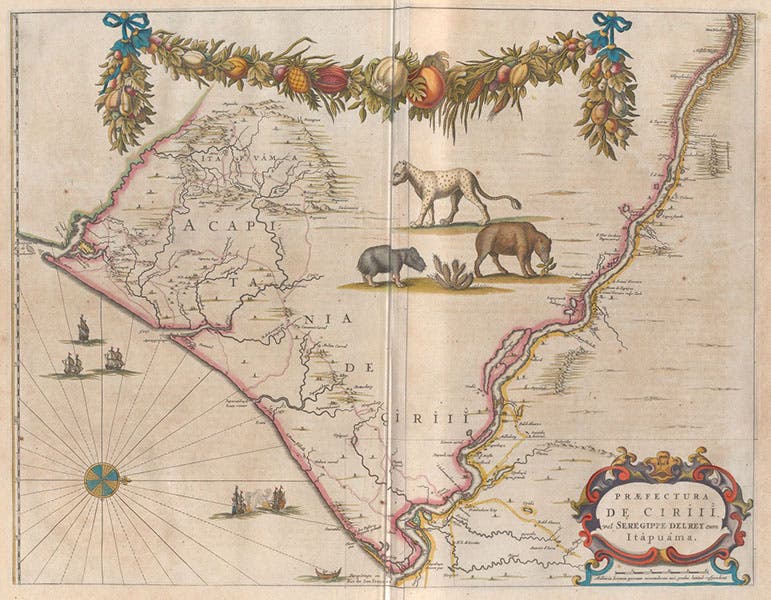

Brazil is one of the few countries that has maps for each province, or prefecture, as the Dutch termed such sub-divisions. We don't show here the map of the entire country, but we do show the prefecture of Ciriji, because the unexplored interior of the prefecture has been decorated with pictures of a capybara (on the fold), and a jaguar, and what might be a paca or a tapir (seventh image).

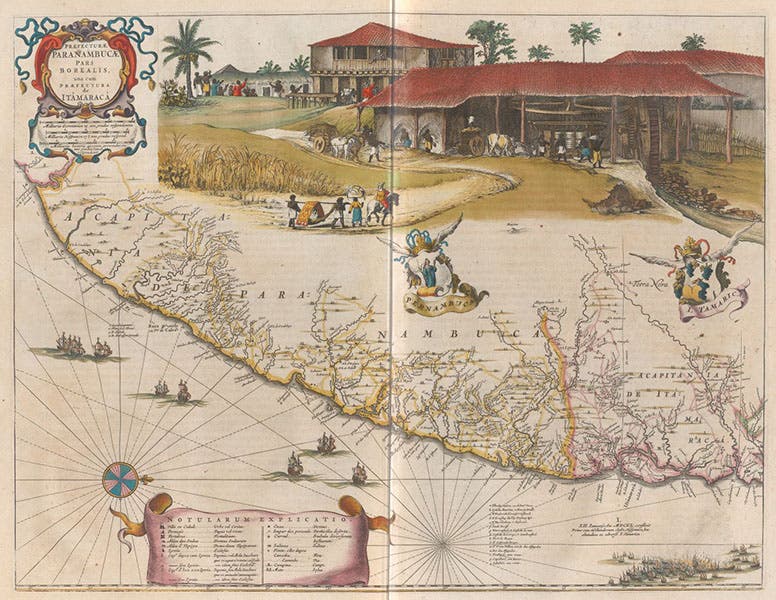

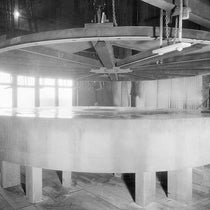

The map of the prefecture of Paranambuca in Brazil (eighth image) is the most striking of all the maps in this volume because it is almost entirely devoted to depicting a sugar cane plantation and sugar processing plant. Just 30 years earlier, the Dutch Prince Frederick William of Orange had established sugar production facilities in Recife, Brazil, and had sent Johann Maurits of Nassau to turn it into a going concern. Maurits took several excellent artists with him, and I suspect one of them made sketches of a sugar plantation and mill that Blaeu was able to get his hands on. He probably obtained his pictures of the capybara and jaguar from the same source.

I had thought about pulling all 11 volumes of the Blaeu Atlas for a group shot, with some of the volumes opened, and the rest just looming ominously, like some vellum Stonehenge. But I wasn’t up to it, not without help. That might be a good project for a snowy winter’s day. It would be an impressive photo.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.