Scientist of the Day - Johan Joosten van Musschenbroek

Johan Joosten van Musschenbroek, a Dutch instrument maker, was born Aug. 2, 1660, in Leiden. He came from a long line of Leiden artisans, who started out making a variety of brass household implements, such as oil lamps. In the late 1660s, Johan's much older brother, Samuel, began making "philosophical instruments,” such as air-pumps and microscopes, which established the direction that the Musschenbroek workshop would take for the next century. One of Samuel's air-pumps, made after the design of Robert Hooke for Robert Boyle, built in 1675, still survives in the Museum Boerhaave in Leiden. It should perhaps be noted that “air-pump” is the early modern term for what we call a vacuum pump.

Samuel died prematurely, only 41 years old, in 1681, and the workshop passed to brother Johan, who was only 21 at the time. He too would die young (at age 46 in 1707), and the workshop would be taken over by Johan's son Jan, who ran it until his own death in 1747. Johan’s younger son Pieter had the leisure to attend university, receive his medical degree, and become a professor of experimental physics at several Dutch universities, ending up in Leiden, where he discovered the Leyden jar. Because Jan and Pieter lived long, and established excellent reputations in their fields, father Johan has always been overshadowed by his sons. Today we give him the limelight.

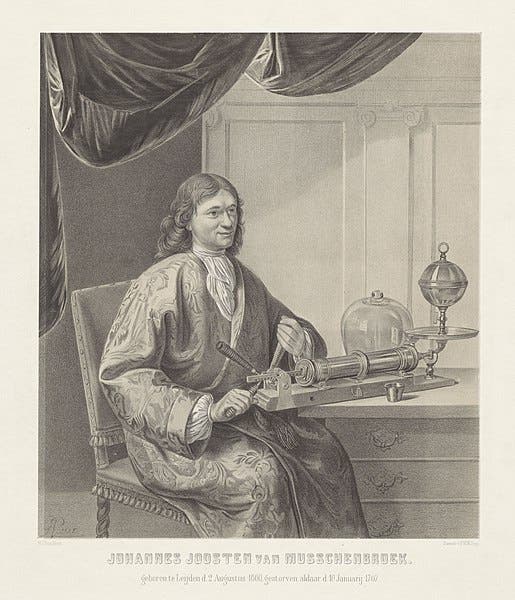

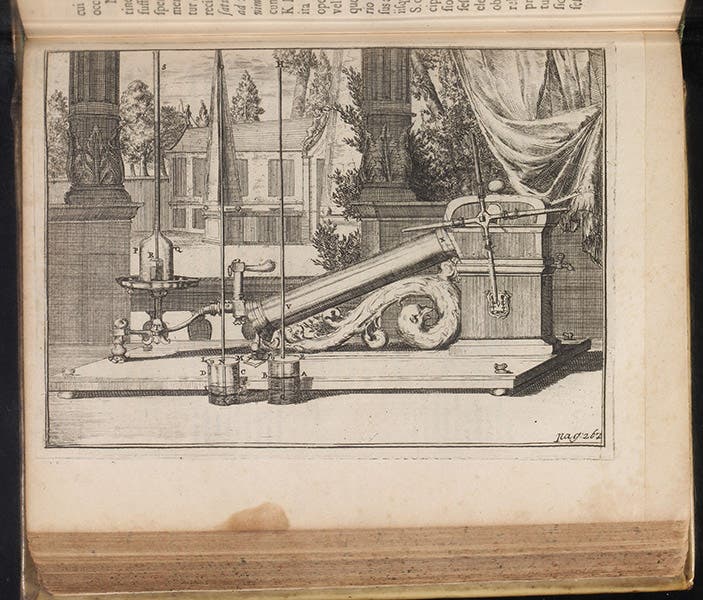

Johan intrigues me because he made and sold a new kind of air-pump. That is not so special – lots of people made new kinds of instruments in the late 17th century. But Johan's air-pump is illustrated numerous times in a variety of works published in the 1680s and 1690s, and that IS unusual. The novelty of the instrument was that the barrel of the pump was set at an incline, so that one man could both turn the handle and operate the valves (with the Hooke/Boyle air-pump, it took two people to do that). Johan’s air-pump is often called the Senguerd-style air-pump, after the natural philosopher who claimed to have invented it, and who first illustrated it in his natural philosophy textbook of 1685. But Senguerd was not an instrument maker, and it seems evident that even though he never gave his craftsmen any credit, it was Samuel van Musschenbroek who first built the new air-pump around 1680, and Johan Joosten who perfected and marketed it.

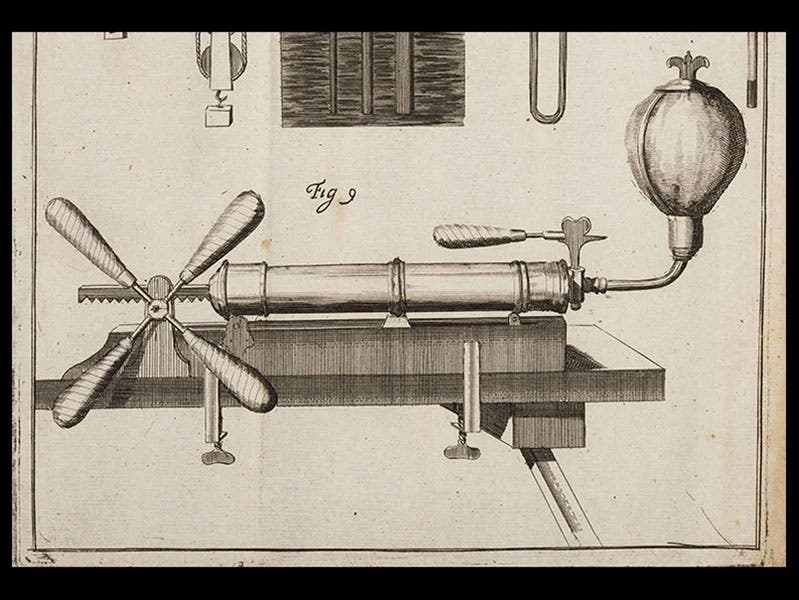

Wolfgang Senguerd succeeded Burchard De Volder as professor of physics at Leiden (De Volder established an experimental physics laboratory at Leiden, the first anywhere; it was for him that Samuel built the Hooke-style air-pump in 1675). Senguerd published his Philosopha naturalis in 1680 (an edition I have not seen) and again in 1685 (we have that edition in the Library). The 1685 edition has two plates demonstrating the inclined air-pump that he claimed as his own invention; we show both of these here (second and third images). The first is the “clean ”version; the second shows details of the valves and rack-and-pinion crank, and the water bath that in practice enclosed the lower end of the pump to prevent air leaks.

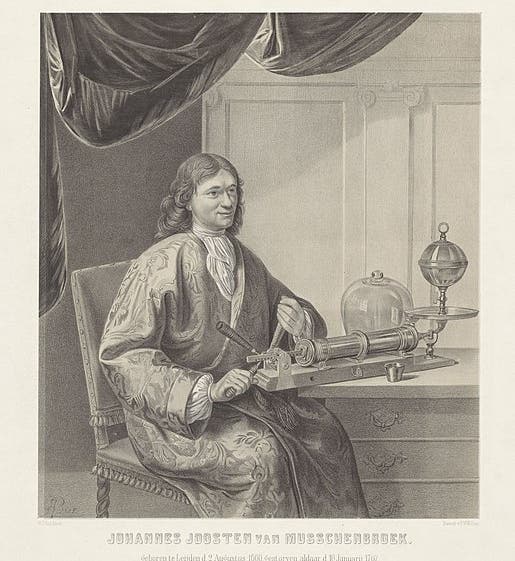

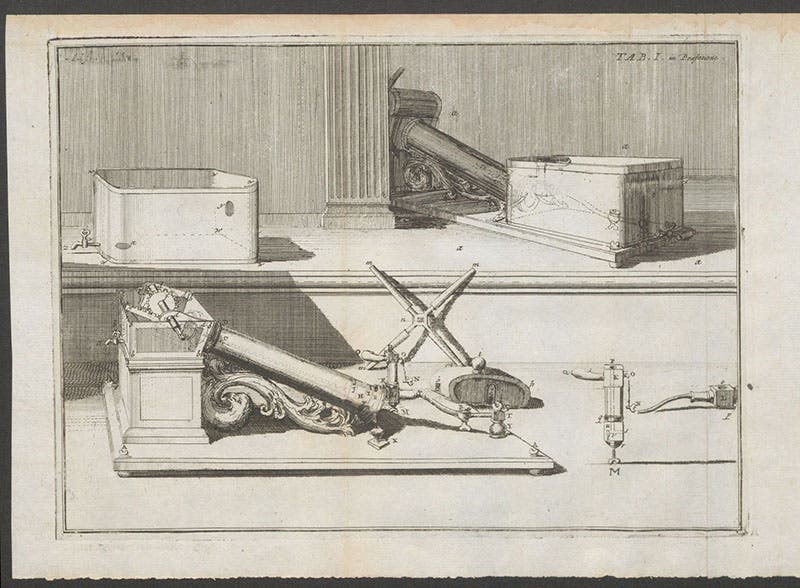

In 1686, James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount of Stair, then living in the Netherlands, published his physics handbook, Physiologia nova experimentalis. He also included an engraving of a Johan Joosten air-pump (fourth image). But this was an improved model, which Senguerd had nothing to do with; it was much smaller, with the barrel now horizontal, and no water-bath was needed. By all accounts, this was Johan’s own invention, and he was clearly proud of it, for when he posed for his portrait in 1686 (first image), he chose to be remembered for the small horizontal pump, which he held on his lap.

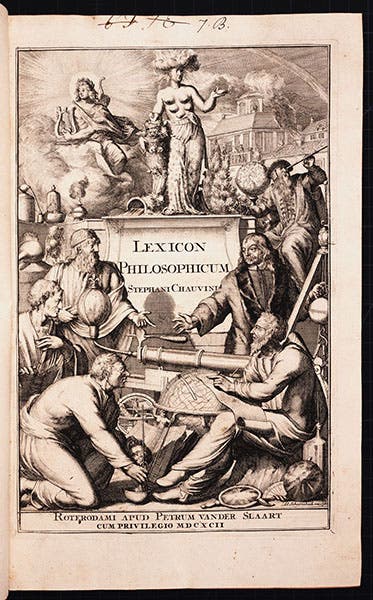

The Musschenbroek air-pump made its final iconographic appearance on the engraved title page of Étienne Chauvin’s Lexicon rationale (1692; fifth image). In this dramatic tableau, Aristotle and Plato, at the left, and René Descartes, standing at the right, are discussing and pointing at a Musschenbroek air-pump. Since none of the three believed in the possibility of a vacuum, their thoughts were probably not happy ones.

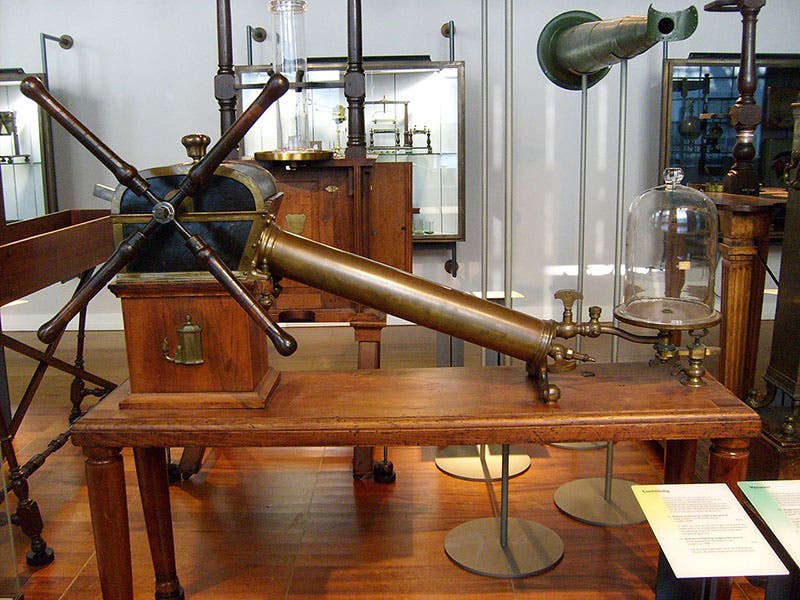

Quite a few air-pumps built by Johann Joosten van Musschenbroek survive, but only one is ever pictured – the one that he built in 1698 for the University of Groningen, which for a long time was in the Museum Boerhave in Leiden, and is now, I believe, back in Groningen (sixth image). This is a Senguerd-style pump, and on the wooden housing of the rack-and-pinion mechanism, there is a brass oil lamp. The “Oriental lamp” was the emblematic device of the Musschenbroek workshop for many years and frequently appeared on their products (why ‘oriental,’ no one knows). This is an especially nice one, and we show a detail in our seventh and last image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.