Scientist of the Day - Johann Conrad Eichhorn

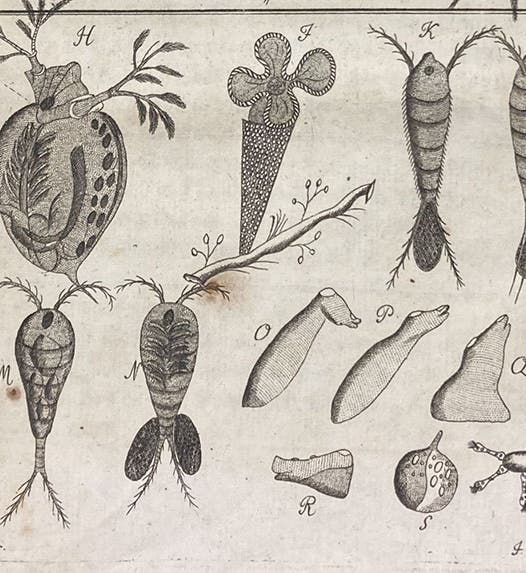

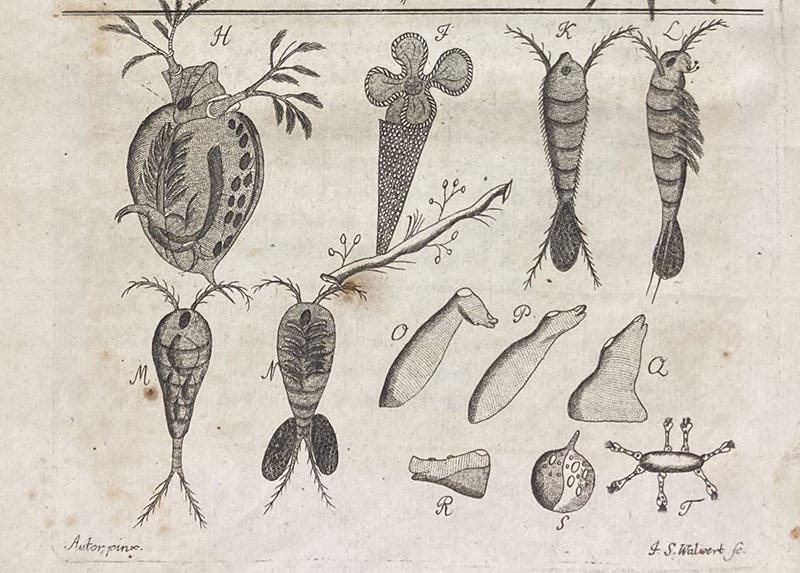

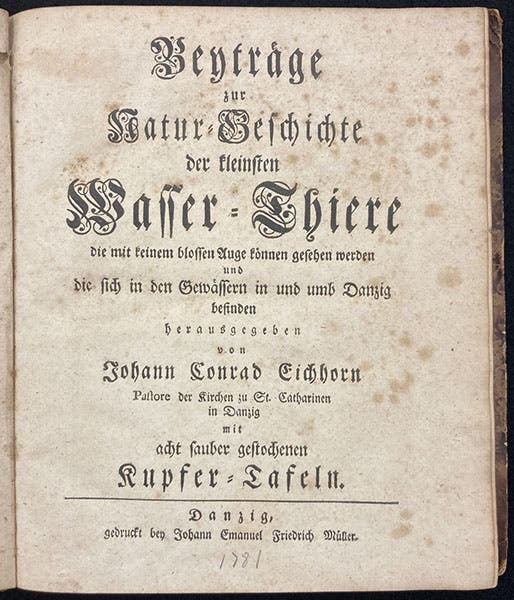

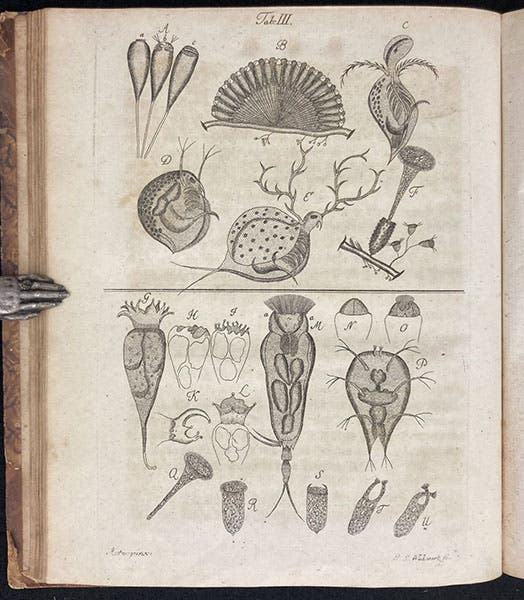

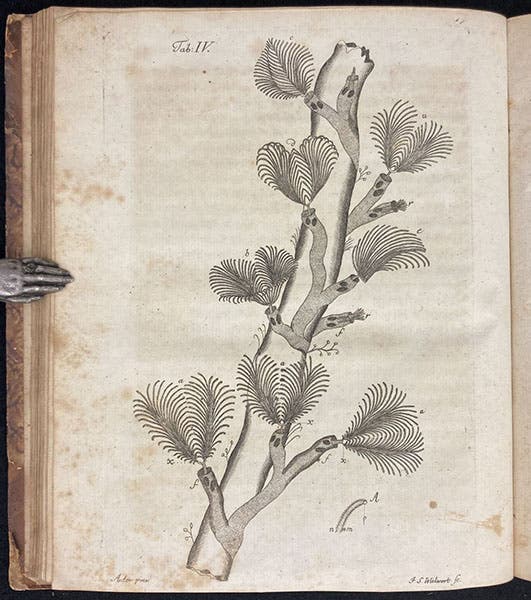

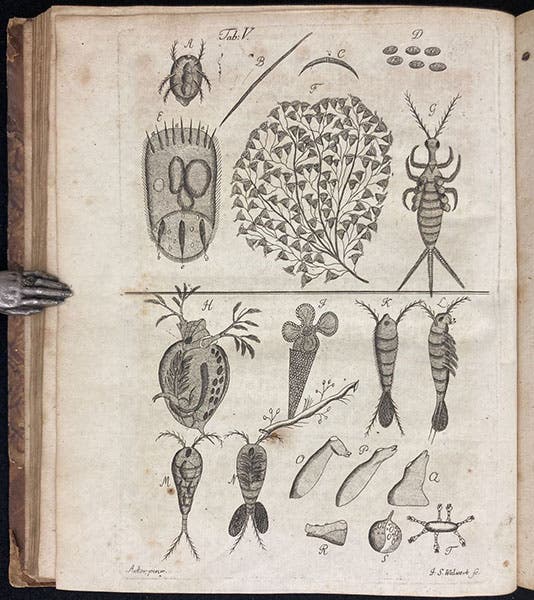

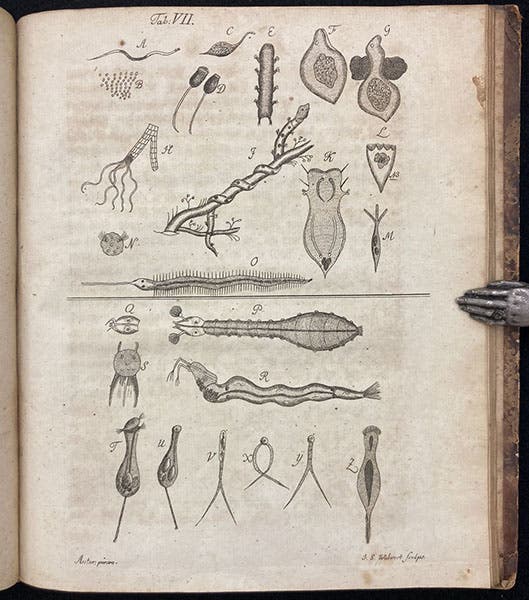

Johann Conrad Eichhorn, a German cleric and amateur naturalist, was born in Danzig (now Gdańsk) on June 2, 1718 (although one usually reliable source has him born on Feb. 6). He spent most of his life as the pastor of St. Catherine's Church in Danzig, and he was apparently a devoted minister to his flock. But he spent most of his flock-free hours with a microscope, examining water samples from the various estuaries and ponds of Danzig, and drawing the water creatures he found there. In 1781, he published a book, Beyträge zur Naturgeschichte der kleinsten Wasserthiere (Contributions to the Natural History of the Smallest Water Animals), illustrated with 8 engravings containing at least a hundred figures made after his own drawings. We have this book in our collections, and all of our images today are from our copy of this publication.

There was a great deal of interest in Germany in the 1770s and 1780s in microscopic organisms, displayed by naturalists such as Jacob Christian Schaeffer (we have written a post on Schaeffer) and Martin Ledermuller (we have not yet done Ledermuller), in which the concern was usually to bring microscopic animals under the umbrella of Linnaean taxonomy and assign them binomial names. Eichhorn could not have cared less about Linnaeus; he just wanted to describe and illustrate the water creatures of Danzig for his fellow citizens, and in the process demonstrate the handiwork of God in fine detail. He was a natural theologian at heart, not a biologist

For names for his "animalcules" (to use the word coined by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek in the 1670s), Eichhorn avoided Latin and gave good German descriptive names like water-buck, water-broom, water-bear, water-louse, water-flea, etc. – the word wasser appears a lot.

I am not much of a microbiologist, but I recognize quite a few of Eichhorn's water creatures, including Daphnia (first and third images), Volvox, Vorticella, Hydra (sixth image), and two copepods (first and fifth images). Considering how hard it is to observe some of these organisms, which rarely sit still, Eichhorn did an amazing job with his drawings. If you look closely at the first image, you can see the signature at bottom left: autor pinx – “the author drew this.” Although he dismissed all claims of being a naturalist in a scientific sense, others recognized the value of his illustrations, and his book was favorably cited well into the next century.

There is not a lot written about Eichhorn. One excellent resource is The Copepodologist’s Cabinet, by David M. Damkaer (American Philosophical Society, 2002), which is supposedly about the history of investigations of copepods, but tends to discuss all sorts of microbiologists, including Eichhorn (who did in fact observe copepods). It was Damkaer who had Eichhorn born on Feb. 6, not June 2, a difference of opinion that will not be resolved by me. Damkaer’s book is a delight to browse though and is one of the first places I look when I am face to face with a little-known protozoologist. I own a copy, and so does the Library.

Our copy of Eichhorn’s book carries the bookplate of Frank Patrick on the inside front cover (eighth image). Mr. Patrick was a Kansas City banker and amateur naturalist and microscopist who amassed an excellent library on microscopy and protozoology. He conveyed his love of microbiology to his daughter Ruth, who became one of the world's foremost experts in limnology and ecology. When Ruth Patrick died in 2013 (at the age of 105!), she left most of her library, which included her father's books, to the Linda Hall Library. We are very grateful for this substantial contribution to our collections.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)