Scientist of the Day - Johann Doppelmayr

Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr, a German astronomer and mathematician, was born Sep. 27, 1677. We profiled Doppelmayr as our Scientist of the Day nearly four years ago, and we focused then on what most people focus on when discussing Doppelmayr, his lovely over-size collection of cosmological maps known as the Atlas coelestis (1742). You may consult the earlier entry to see what all the fuss is about.

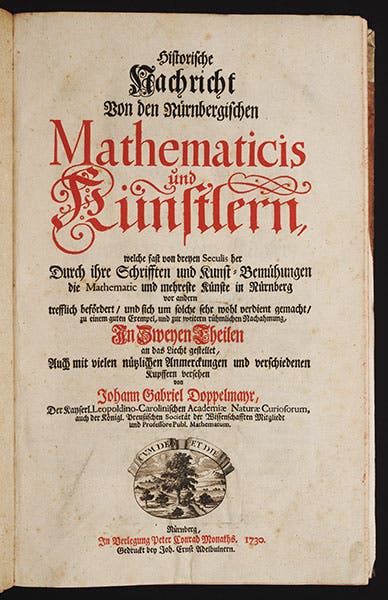

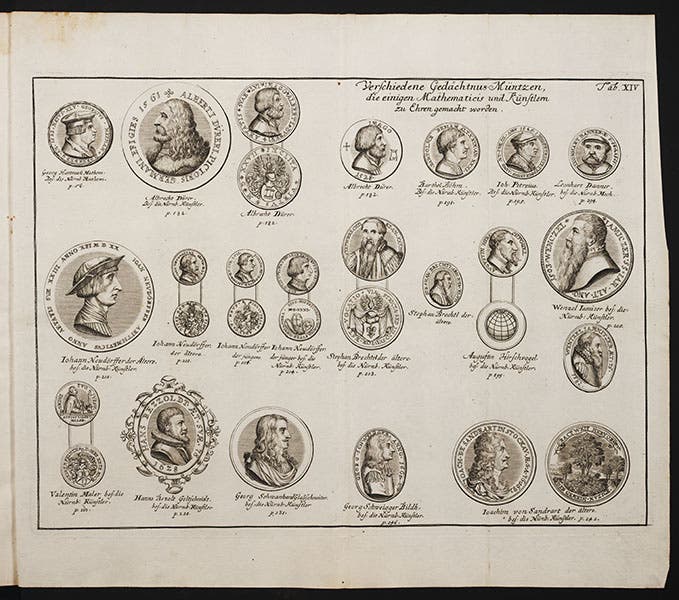

Today, we direct attention to a lesser-known but important Doppelmayr publication, the Historische Nachricht (1730), a history of mathematicians and artists of Nuremberg, Doppelmayr's home city. This is a different kind of Nuremberg Chronicle, with short biographical accounts of a variety of scholars and painters, along with medallion portraits of many of them (third image).

Albert Dürer figures prominently, as many commemorative medals were struck in his honor that Doppelmayr reproduces, but we don't need his Nachricht to tell us what Dürer looked like, since Dürer himself was so obliging with self-portraits. But suppose you wanted a portrait of Johannes Petreius, the respected Nuremberg printer who published the De revolutionibus of Nicolaus Copernicus in 1543. You would look long and hard to find a representation, unless you started with the Nachricht, in which case you would find one right away (fourth image, far right).

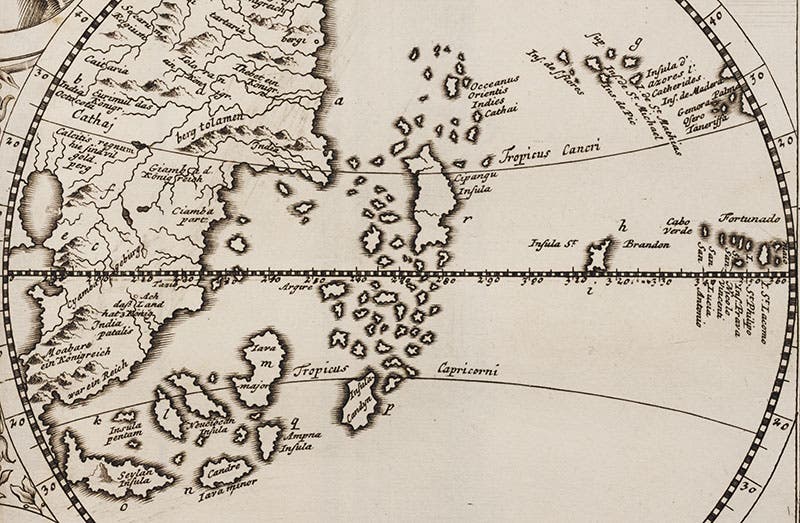

Perhaps the most valuable section in this book is the account of Martin Behaim. Behaim had travelled down the coast of Africa in the 1480s on a Portuguese exploratory voyage, and in 1485 he even sat in judgment of the Columbus brothers’ appeal for Portuguese backing for a trans-Atlantic voyage (Behaim voted with all the committee members to reject the proposal). Perhaps this is why the city fathers of Nuremberg, in 1492, commissioned Behaim to construct a globe of the world reflecting the latest geographical knowledge. Behaim made a world map and then constructed a 21-inch papier-mâché globe with a vellum outer skin, hiring an artist to paint the map onto the sphere. It was beautifully done, with thousands of locations and hundreds of inscriptions filling the open spaces. Most significantly, the continents of Europe and Asia extended well around the front half of the globe, so that the island of Cipangu (Japan), on the back side, lay little more than 3000 miles from Spain. Columbus had already departed on his first voyage (his second petition was more successful), before the Behaim globe was completed, but the world in the head of Columbus was the world on Behaim’s globe, a world where one could easily reach China and the Indies by sailing west.

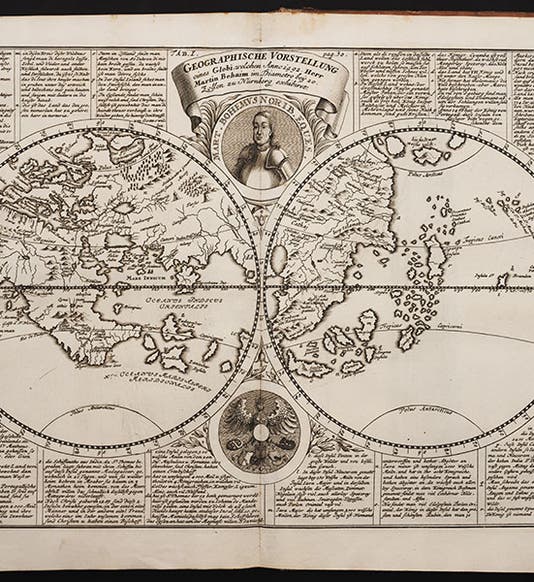

The Behaim globe is still with us – it is the oldest surviving terrestrial globe in the world, and resides in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg - but it is difficult to see what is on it, even if you are looking at it first-hand. This was true even in Doppelmayr's day, so he did us all an immense favor by reproducing the hemispheres of the globe as an engraving, and transcribing all the inscriptions. We see here both the full map (first image), and a detail of the Atlantic Ocean and the position of Cipangu (fifth image).

We also show a detail of top center of the map, which contains a portrait of Behaim himself (sixth image). There is a statue of Behaim and his globe in Nuremberg. But it is not contemporary. The closest we have to an actual likeness of Behaim is the medallion in Doppelmayr's Nachricht.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.