Scientist of the Day - Johann Friedrich Gmelin

Johann Friedrich Gmelin, a German naturalist, was born Aug. 8, 1740, in Tübingen. His grandfather had founded an Apotheke (apothecary) in Tubingen, and had sired three sons, one of whom took over the Apotheke, with the other two becoming chemists and professors at the University of Tübingen. The third generation, which included Johann Friedrich, sported another apothecary and two more professors, one at St. Petersburg, and one (Johann Friedrich) at Göttingen. The fourth generation produced two more professors of chemistry, at Tübingen and Heidelberg, but alas, no apothecary, so the pharmacy left the family, but it still stands on its street corner in Tübingen, with the new proprietors still filling prescriptions, but under a different name (second image).

A dynasty such as the Gmelins is unusual in science. There are lots of distinguished father-and-son pairs, and a few father-daughter or mother-daughter twosomes or threesomes, but a four-generation dynasty is most uncommon. The Cassini family of astronomers in France is the only other one I can think of that spanned four generations, but there was only one scientist per generation. The Gmelins produced 6 chemists, all university professors, and three pharmacists, over a period of 150 years. That is quite remarkable.

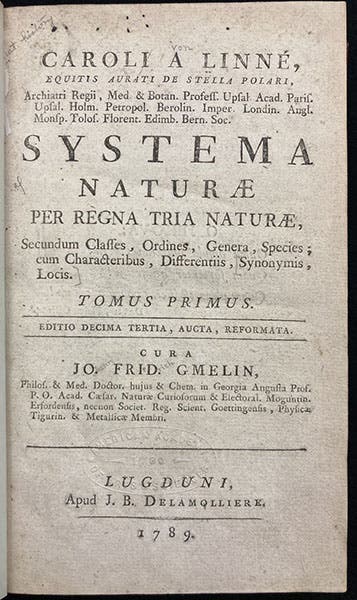

Johann Friedrich stands out in the Gmelin family tree because he was more interested in botany and zoology than chemistry. In the 1760s, when he was in his twenties, he met Carl von Linné (Linnaeus) and became quite interested in Linnaeus’s project to introduce binomial nomenclature (as in Canis lupus) into plant and animal taxonomy. Linnaeus had made a good start at this in his Systema naturae, 10th ed. (1758-59), but new species were being discovered at a rapid rate in the last half of the 18th century, and after Linnaeus died in 1778, it took a lot of help to keep the ball rolling. Gmelin did his part by editing and publishing the 13th edition of Linnaeus's Systema naturae beginning in 1788. By that time, most of the discoveries made by Capt. Cook's naturalists had been named and described, so Gmelin took it upon himself to bring them all into the system of Nature.

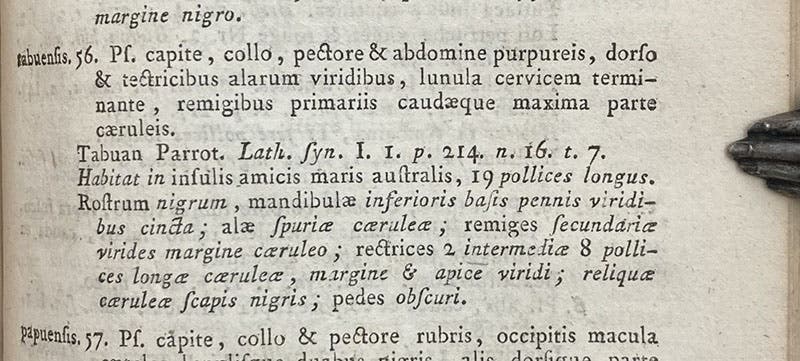

Unfortunately, not all naturalists in the 1770s and 1780s were followers of Linnaeus, and many had no interest in two-word Latin names. Such a man was John Latham, an English birdman who published A General Synopsis of Birds in 1781-85, with many new species that Latham named, such as a parrot from Tonga, which he named: the Tabuan parrot, and illustrated in his book (fourth image). In the 13th. edition of the Systema naturae, Gmelin included the bird, cited Latham as his souce, and renamed it Psittacus tabuensis, a proper Linnaean binomial (fifth image).

Unfortunately for Laham, and fortunately for Gmelin, the custom grew, as the Linnaean system became accepted everywhere, that the first person to publish a description of a species with a proper Latin binomial name would get credit for the discovery of that species, and have an abbreviation of their last name attached to the species name, even if the generic name changed, as often happens. Look up the Black-headed Bulbul in Wikipedia (or let me do it for you) and you will find that it is referred to as Brachypodius melanocephalos (Gmelin, JF 1788), even though Latham first described it in 1781 as the black-headed shrike. Zoological fame can be fickle and fleeing. But not for J.F. Gmelin.

It would be nice for the dynasty if all the Gmelins were buried in one place, but they are not. Johann Friedrich, who died in 1804, was buried with his wife Rosine Louise in the Albani cemetery in Göttingen (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.